Koniuchy massacre

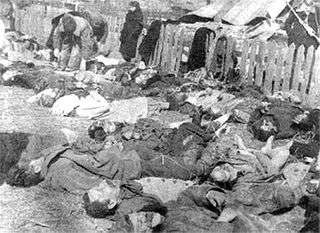

The Koniuchy (Kaniūkai) massacre was a World War II massacre of Polish and Byelorussian[1] civilians, including women and children,[2] carried out in the village of Koniuchy (now Kaniūkai, Lithuania) on 29 January 1944 by a Soviet partisan unit together with a contingent of Jewish partisans under Soviet command.[1][2] Between 30 and 40 civilians were killed, and dozens were injured.[1]

In 2001, Polish authorities launched an investigation into the massacre; it was closed in 2018, as the authorities were not able to identify any living perpetrators. In 2004, Lithuanian authorities launched their own investigation into the massacre and sought to interview former Jewish partisans; this was seen by observers in the West and among Jewish groups as politically motivated, and the Lithuanian investigation was closed in 2008.[1]

Background

Koniuchy, now known as Kaniūkai, is a village located in Lithuania near the Belarus–Lithuania border. Before the Second World War, it belonged to the Second Polish Republic and, after the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939, it was transferred to Lithuania according to the Soviet–Lithuanian Mutual Assistance Treaty. Lithuania was occupied by the Soviet Union in June 1940 and by Nazi Germany in June 1941. According to the census, carried out in August 1942 in Generalbezirk Litauen, the village had 374 people – 41 of them declared their nationality as Lithuanians, 17 as Poles, and the rest chose ambiguous "of Lithuania".[3]

Soviet partisans became more active in the area in 1943. Koniuchy is located at the edge of the Rudniki Forest (now Rūdininkai Forest), where partisan groups, both Soviet and Jewish, set up their bases from which they attacked the German forces.[4] Unlike Polish partisans of Armia Krajowa (Home Army), these partisans did not enjoy widespread local support and could not depend on voluntary food contributions from local farmers.[5] Therefore, Soviet partisans regularly raided nearby villages to obtain food stocks, cattle, and clothing.[6] This raiding led to clashes between the farmers and the partisans. In response, German administration deployed Lithuanian Auxiliary Police Battalions in the area and provided weapons to local self-defence units.[7]

Village self-defence

As raiding intensified in summer 1943, men of Koniuchy organized an unarmed night guard.[8] In early fall 1943, the village was visited by four Lithuanian policemen and the men agreed to organize an armed self-defence group. According to later testimony by its leaders, the group grew from initial 5 or 6 members to 25–30 men.[9] There is no reliable data on the group's weapons.[10] Soviet sources, attempting to exaggerate the threat posed by Koniuchy, claimed that the village had three machine guns and automatic rifles.[11] One of the leaders of the self-defence unit Vladislavas Voronis in his post-war trial by NKVD, trying to minimize his anti-Soviet activities, claimed that the group had only eight rifles and ten sawed-off shotguns. It is likely that at least some weapons were provided by the Lithuanian policemen of the 253rd Police Battalion which had an outpost in Naujosios Rakliškės.[11]

There were several incidents between the partisans and the men of Koniuchy. On October 13, 1940, a group of six armed Soviet partisans took three cartloads worth of food, clothes, and other items. The villagers stopped the partisans on a bridge over Šalčia and took back the property.[11] In January 1944, a Soviet partisan was killed in Didžiosios Sėlos in an operation that involved a few men from Koniuchy. Soviet sources claimed that the partisan was captured, transported to Koniuchy, tortured, and later executed. Similarly, Soviet sources implicated men from Koniuchy in attacks on Soviet partisans in Visinčia and Kalitonys.[12] In a November 2008 interview, York University professor Sara Ginaitė, a veteran Jewish partisan fighter, described Koniuchy as having a record of hostility to the partisans and that, in collaboration with the Nazis and the local police, the town had organized an armed group to fight the partisans.[13] According to Soviet and Jewish sources, the villagers constituted a pro-Nazi threat to the partisans, though collaboration was denied by the villagers who claimed that only a few men in the village were armed with rifles for self-protection.[1]

Massacre

On 29 January 1944, around 6 a.m., the village was attacked by Soviet partisan units under the command of the Central Partisan Command in Moscow. The raid was carried out by 100–120 partisans from various units including 30 Jewish partisans from the "Avengers" and "To Victory" units under the command of Jacob (Yaakov) Prenner.[14]

Between 30 to 40 villagers were killed and a dozen more were wounded, and many houses were looted and burned.[1] Polish authors compiled a list of 38 names. Among them, there were 11 women and 15 children under the age of 16.[15] According to reports of the Lithuanian Security Police, 36 houses, 40 granaries, 39 barns, and one banya were burned down, 50 cows, 16 horses, about 50 pigs, and 100 sheep were slaughtered.[15] The massacre of Koniuchy and murder of its inhabitants was documented by one of the attacking partisans, Chaim Lazar. According to Lazar the village was to be destroyed completely[16] as an example to others, and even the livestock was to be killed.[17][18]

Investigation and controversy

The Polish Institute of National Remembrance initiated a formal investigation into the incident on 3 March 2001, at the request of the Canadian Polish Congress.[19] The institute examined a number of archival documents including police reports, encoded messages, military records and personnel files of the Soviet partisans. Requests for legal assistance were then sent to state prosecutors in Belarus, Lithuania, the Russian Federation and Israel. The IPN investigation was closed in February 2018. The official reason for the closure was that the investigators were not able to establish "beyond a reasonable doubt" that any perpetrators of the massacre were still alive, and as a result concluded that there was no one who could be charged with a crime.[20]

The Lithuanian prosecutor general subsequently opened its own investigation into the massacre in 2004.[1] As part of its investigation, Lithuanian prosecutors sought out Jewish veterans of the partisan movement. One of these was Yitzhak Arad, a former Israel Defense Forces brigadier general, an expert on the Holocaust in Lithuania, and former chairman of Yad Vashem. Arad had also served as a member of a commission appointed by Lithuania's president in 2005 to examine past war crimes. In response to the investigation, Yad Vashem issued a protest saying it focused on "victims of Nazi oppression" and suspended Israeli participation in the commission which Arad was part of.[21][2][22] Following wide international criticism (and some domestic criticism) the Lithuanian investigation was closed in September 2008.[23]

.jpg)

Commemoration

In May 2004, a memorial cross commemorating the event was erected in Kaniūkai with the known names of the victims.[24]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Suziedelis, Saulius A. (2011-02-07). Historical Dictionary of Lithuania. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810875364.

- 1 2 3 Polonsky, Antony; Michlic, Joanna B. (2009-04-11). The Neighbors Respond: The Controversy over the Jedwabne Massacre in Poland. Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400825814.

- ↑ Zizas, Rimantas (2014). Sovietiniai partizanai Lietuvoje 1941–1944 m. (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas. p. 466. ISBN 978-9955-847-88-5.

- ↑ Zeleznikow, John (2010). "Life at the end of the world: a Jewish Partisan in Melbourne". Holocaust Studies. 16 (3): 11–32. ISSN 1750-4902.

- ↑ Zizas 2014, p. 490.

- ↑ Informacja o śledztwie dotyczącym zbrodni popełnionej w Koniuchach

- ↑ Zizas 2014, pp. 467–469.

- ↑ Zizas 2014, p. 470.

- ↑ Zizas 2014, pp. 470–471.

- ↑ Zizas 2014, p. 471.

- 1 2 3 Zizas 2014, p. 472.

- ↑ Zizas 2014, p. 473.

- ↑ Adam Fuerstenberg. Lithuania asks partisans to 'justify' their actions. The Canadian Jewish News. 20 November 2008. (retrieved 1 May , 2017)

- ↑ "Operations Diary of a Jewish Partisan Unit in Rudniki Forest 1943–1944". Jewish Virtual Library. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- 1 2 Zizas 2014, p. 491.

- ↑ Stachura, Peter (2004). Poland, 1918-1945: An Interpretive and Documentary History of the Second Republic. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781134289493.

- ↑ Sowjetische Partisanen 1941-1944: Mythos und Wirklichkeit Bogdan Musial Ferdinand Schoeningh, 2009, page 547

- ↑ Bogdan Musial Sowjetische Partisanen in Weißrussland Innenansichten aus dem Gebiet Baranovici 1941-1944 Cover: Sowjetische Partisanen in Weißrussland Oldenbourg Verlag, München 2004, page 28

- ↑ Marc Perelman. Poles Open Probe Into Jewish Role In Killings. Group Fingers WWII Partisans. The Forward. 8 August 2003.

- ↑ Wybranowski, Wojciech (February 16, 2018). "IPN umarza śledztwo w sprawie masakry w Koniuchach".

- ↑ Lana Gersten and Marc Perelman. Tensions mount over probe into Jewish 'war crimes'. Haaretz. 8 July 2008.

- ↑ Sara Ginaite. ‘Investigating’ Jewish Partisans in Lithuania. The Protest of a Veteran Jewish Partisan. Jewish Currents. September 2008.

- ↑ Bringing the Dark Past to Light: The Reception of the Holocaust in Postcommunist Europe, John-Paul Himka and Joanna Michlic, pages 339-342.

- ↑ Tumavičius, Andrius (February 2014). "Kaniūkų kaimo tragedija" (PDF). Atmintinos datos (in Lithuanian). Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

Further reading

- Lazar, Chaim (1985). Destruction and Resistance: A History of the Partisan Movement in Vilna. Translated by Galia Eden Barshop. New York: Shengold Publishers. ISBN 978-0884001133.

- Kowalski, Isaac (1969). A Secret Press in Nazi Europe: The Story of a Jewish United Organization. New York: Central Guide Publishers. OCLC 925932918.

- Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, Intermarium: The Land between the Baltic and Black Seas (New Brunswick, New Jersey and London: Transaction, 2012), 500–519 ("Koniuchy: A Case Study")

- Mark Paul, Tangled Web: Polish-Jewish Relations in Wartime Northeastern Poland and the Aftermath, Part 3 (Toronto: PEFINA Press, 2017) ("Civilian Massacres—The Case of Koniuchy") posted at: http://www.kpk-toronto.org/obrona-dobrego-imienia/

- Report from IPN on Poland