Kirtland's warbler

| Kirtland's warbler | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Male in Michigan, United States | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Setophaga |

| Species: | S. kirtlandii |

| Binomial name | |

| Setophaga kirtlandii (Baird, 1852) | |

| |

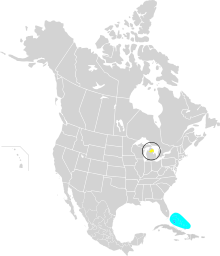

| Range of S. kirtlandii Breeding range Winter range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dendroica kirtlandi (lapsus) | |

Kirtland's warbler (Setophaga kirtlandii ), also known as the jack pine warbler, is a small songbird of the New World warbler family (Parulidae), named after Jared P. Kirtland, an Ohio doctor and amateur naturalist. Nearly extinct just 50 years ago, it is well on its way to recovery. It requires large areas, greater than 160 acres (65 hectares), of dense young jack pine for its breeding habitat. This habitat was historically created by wildfire, but today is primarily created through the harvest of mature jack pine, and planting of jack pine seedlings.

Since the mid-19th century at least it has become a restricted-range endemic species. Almost the entire population spends the spring and summer in Southern Ontario or the northeastern Lower Peninsula of Michigan in their breeding range and winters in The Bahamas. A small population breeds in Wisconsin.

Description

Kirtland's warbler has bluish-brown upper body parts, dark streaks on the back, yellow underparts, and streaked flanks. It has thin wing bars, dark legs, and a broken white eye ring. Females and juveniles are browner on the back. Like the palm warbler and prairie warbler, it frequently bobs its tail. At 14–15 cm (5.5–5.9 in) and 12–16 g (0.42–0.56 oz), it is the largest of the numerous Setophaga warblers.[2] Its song is a loud chip-chip-chip-too-too-weet-weet often sung from the top of a snag (dead tree) or northern pin oak (Quercus ellipsoidalis) clump.

Range and ecology

The breeding range of Kirtland's warbler is in a very limited area in the north of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan. In recent years, breeding pairs have been found in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Wisconsin, and southern Ontario likely due to the rapidly expanding population. Breeding habitat is typically large areas (> 160 acres) of dense young jack pine (Pinus banksiana). Kirtland's warblers occur in greatest numbers in large areas that have been clearcut or where a large wildfire has occurred. The birds leave their breeding habitat between August and October and migrate to The Bahamas and nearby Turks and Caicos Islands; they return to Michigan to breed again in May. In their winter habitat, they have been found primarily in scrub habitat, feeding on wild sage, black torch, and snowberry.

Kirtland's warblers forage in the lower parts of trees, sometimes hovering or searching on the ground. These birds eat insects and some berries, also eating fruit in winter. For breeding they require stands of young (4 to 20 year old, 2–4 m high) jack pine trees. They nest on the ground. Their nest is usually at the base of a tree, next to a down log or other structure, and is well concealed by sedge, grasses, blueberries and other ground vegetation.

Habitat

Ecology of jack pine

Jack pine is a species of somewhat smallish pine widespread from the Canadian tundra and taiga to the Great Lakes region and the Atlantic Ocean; it is a boreal species, only occurring in a certain climate.[3] Its cones open only after trees have been cleared away by forest fires or, after logging, in the summer sun. About all of its present-day range was covered by solid ice as late as 10,000 to 15,000 years ago; the range of jack pine (and as it seems Kirtland's warbler also) was probably a contiguous swath between the Appalachian Mountains and the Great Plains. The jack pine's peculiar reproductive strategy fits well with a dry taiga or cool temperate habitat as would have predominated there, probably with a higher incidence of forest fires than today, as the ice age climate was somewhat drier overall.[4]

Decline to near-extinction

As global climate changed out of the ice age through the last 10 millennia or so, jack pine, and consequently also Kirtland's warbler, shifted their habitat north. As the Kirtland's warbler—and Parulidae in general—is not able to expand into subarctic climate well, most jack pine woods are too far north for the species. Moreover, the Great Lakes, which formed before the receding ice, were an obstacle for its spread. Kirtland's warbler found itself blocked by the expanse of water, while the cold-hardy jack pine expanded its range as far as the Northwest Territories.

With European settlement of North America progressing in earnest, much of the forest in the southern Great Lakes region was cut away, never to be restocked. Kirtland's warbler became trapped on the northern Lower Peninsula. It may or may not have occurred in Dr. Kirtland's home state of Ohio in recent times, but if it did it would seem to have been extirpated from the state around the time when its namesake himself died in 1877. What habitat there might have been was cleared away in the latter half of the 19th century, and certainly the bird was not breeding there anymore in 1906.[5] Kirtland's warblers used to breed in Ontario but have not done so since the 1940s. By the mid-20th century its numbers had crashed to near-extinction. The Kirtland's warbler population reached lows of probably less than 500 individuals around the 1970s, and in 1994 only 18 square kilometres (6.9 sq mi) of suitable breeding habitat was available.[1][6]

Recovery

In 1976 the Kirtland's Warbler Recovery Plan was developed, and updated once again in 1985. It was developed in order to provide management in efforts to increase the Kirtland warbler's population. Using these management techniques, the goal is to sustain 1,000 pairs of Kirtland's warbler, both male and female. A major portion of this plan is habitat management around the Roscommon area. The first objective is to develop and maintain anywhere from 36,000 to 40,000 acres (14,570 to 16,190 hectares) of reasonable nesting habitat for Kirtland's warbler. The second objective is to protect the warbler on wintering grounds, and to form an ideal migration problem. Other goals include: reducing harmful factors in order to increase survival rates amongst the population, monitoring breeding, and keeping an accurate census in order to evaluate the total population in correlation to environmental factors. Finally, under the last portion of the Recovery Plan, there is a development and implementation of emergency measures to prevent total extinction. With all these key factors successfully completed, the life of the Kirtland's warbler will be sustained.

Today the habitat of Kirtland's warbler is being preserved by controlled or prescribed burns and staggered timber harvests in its limited breeding range. The DNR, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Forest Service coordinate the clear cutting of tracts of 50 year old jack pines on 23 Kirtland's Warbler management units. These managed units total 220,000 acres (89,000 ha). After cutting, new trees are planted in a specified pattern to mimic the natural habitat the warbler needs, with clearings and dense thickets. This management program also provides habitat for other species such as small animals, other birds, deer, porcupines, and turkeys. Since this habitat management regime began in the 1970s, the numbers of Kirtland's warbler have steadily risen, with an estimated population of 5,000 in 2016.[7]

Kirtland's warbler was, and is, threatened by nest parasitism by the brown-headed cowbird, to which warblers are highly susceptible. The cowbird naturally fed on buffalo ectoparasites. With the destruction of the large buffalo herds, the cowbird sought other sources of food, bringing it into contact with Kirtland's warbler. In the 1960s, 70% of warbler nests were parasitized by cowbirds, reducing the number of warbler chicks to fewer than needed to perpetuate the species. Specially designed cowbird traps capture 4,000 cowbirds a season, reducing the number of warbler nests with cowbird chicks to well below the level that endangers the warbler.[7]

Kirtland's warbler has been observed in Ontario and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and rarely recorded in NW Ohio (where there is hardly any significant woodland left), the numbers of recorded birds are increasing.[8] Beginning in 2005, a small number have been observed in Wisconsin. In 2007, three Kirtland's warbler nests were discovered in central Wisconsin[9] and one at CFB Petawawa,[10] providing an auspicious sign that they are recovering and expanding their range once again. The Wisconsin population continues to grow, with 53 individuals and 20 nests recorded in 2017.[11]

The Kirtland's warbler is listed as "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act of 1973,[12] and was proposed to be removed from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife in 2018.[13] Although there seem to be no more than 5,000 Kirtland's warblers as of late 2007,[14] four years earlier they had numbered just 2500–3000. On the IUCN "Red List of Threatened Species," the Kirtland's warbler was classified as vulnerable to extinction since 1994, but was downlisted to near threatened in 2005 due to its encouraging recovery. The birds depend on Bahamas feeding during winter.[7] Changes to their Bahamas habitat may eventually become a bigger threat to the birds' recovery than the situation in its breeding range.[1]

There is a Kirtland's Warbler Festival, which is sponsored in part by Kirtland Community College (which is named in honor of the bird and its habitat).

The public radio program Radiolab included a piece on the extraordinary efforts to restore the Kirtland Warbler habitat. It is entitled 'Oops' and is the first show of season 8.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 BirdLife International (2012). "Dendroica kirtlandii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Tiner, Tim (2013) Kirtland’s warbler. ON Nature magazine . Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

- ↑ Peel, M.C.; Finlayson, B.L.; McMahon, T.A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification" (PDF). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. 11 (5): 1633–1644. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. Supplement

- ↑ Ray, Nicolas; Adams, Jonathan M. (2001). "A GIS-based Vegetation Map of the World at the Last Glacial Maximum (25,000–15,000 BP)". Internet Archaeology. 11.

- ↑ Henninger, W.F. (1906). "A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 18 (2): 47–60.

- ↑ "Kirtland's Warbler". Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 2015-10-22.

- 1 2 3 The Detroit Free Press, "BACK FROM THE BRINK OF EXTINCTION", by Kathleen Lavey, page 11A, 3 July 2016

- ↑ Ohio Ornithological Society (2004): Annotated Ohio state checklist Archived 2004-07-18 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ United States Fish and Wildlife Service (2007): Kirtland's Warbler 2007 Nesting Season Summary. Version of 2007-DEC-10. Retrieved 2008-FEB-19.

- ↑ CFB Petawawa (2007): Canada's Rarest Nesting Bird found at CFB Petawawa. Version of 2007-Nov-01. Retrieved 2008-FEB-19.

- ↑ "Kirtland's warblers find Wisconsin a good place to nest". FWS.gov. US Fish and Wildlife Service. 16 January 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

From only 11 Kirtland’s and three nests found in Adams County in 2007 to 53 individuals and 20 total nests among Adams, Marinette and Bayfield counties in 2017, the population has grown and geographically expanded in our decade of conservation work

- ↑ U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Species Profile for Kirtland's Warbler Archived 2009-09-04 at the Wayback Machine.. Ecos.fws.gov. Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

- ↑ "Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Removing the Kirtland's Warbler From the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife" (PDF). Federal Register. 12 April 2018. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ USFWS: Kirtland's Warbler Census Results: 1951–2008. Fws.gov (2013-01-03). Retrieved on 2013-04-03.

Further reading

- Clench, Mary Heimerdinger (1973). "The Fall Migration Route of Kirtland's Warbler". Wilson Bulletin 85 (4): 417–428.

- Cooper NW, Hallworth MT, Marra PP (2017). "Light-level geolocation reveals wintering distribution, migration routes, and primary stopover locations of an endangered long-distance migratory songbird". Journal of Avian Biology. 48 (2): 209–219. doi:10.1111/jav.01096.

- Mayfield, Harold (1960). "The Kirtland's Warbler". Cranbrook Institute of Science Bulletin (40): 1-242.

- Mayfield, Harold F (1992). Kirtland’s Warbler. In: Poole A, Stettenheim P, Gill F (editors) (1992). The Birds of North America, No. 19. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Academy of Natural Sciences / Washington, District of Columbia: The American Ornithologists' Union.

- Rapai, William J. (2012). The Kirtland's Warbler: The Story of a Bird's Fight Against Extinction and the People Who Saved It. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11803-8. ISBN 978-0-472-02806-1.

- Sykes, Paul W., Jr.; Clench, Mary Heimerdinger (1998). "Winter Habitat of Kirtland's Warbler: An Endangered Nearctic/Neotropical Migrant". Wilson Bulletin 110 (2): 244–261.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Setophaga kirtlandii. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Setophaga kirtlandii |

- "How a tiny, rare songbird flies 3,400 miles and comes home to Michigan". MLive.com. Retrieved 2018-05-09.

- http://www.uptownupdate.com/2015/05/rare-bird-alights-at-montrose-harbor.html

- Kirtland's warbler at All About Birds

- Kirtland Warbler Festival and links

- Kirtland's warbler, Michigan Department of Natural Resources

- The Nature Conservancy Songbirds: Kirtland's warbler

- Endangered species program, Kirtland's warbler, US Fish and Wildlife Service

- Stamps

- USDA Huron-Manistee National Forests Kirtland's warbler page

- Kirtland's Warbler at Radio Lab