Kilroy was here

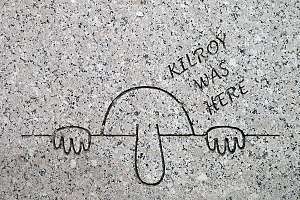

Kilroy was here is an American expression that became popular during World War II, typically seen in graffiti. Its origin is debated, but the phrase and the distinctive accompanying doodle became associated with GIs in the 1940s: a bald-headed man (sometimes depicted as having a few hairs) with a prominent nose peeking over a wall with his fingers clutching the wall.

"Kilroy" was the American equivalent of the Australian Foo was here which originated during World War I. "Mr Chad" or just "Chad" was the version that became popular in the United Kingdom. The character of Chad may have been derived from a British cartoonist in 1938, possibly pre-dating "Kilroy was here". According to Dave Wilton, "Some time during the war, Chad and Kilroy met, and in the spirit of Allied unity merged, with the British drawing appearing over the American phrase."[1] Other names for the character include Smoe, Clem, Flywheel, Private Snoops, Overby, The Jeep, and Sapo.

According to Charles Panati, "The outrageousness of the graffiti was not so much what it said, but where it turned up."[2] It is not known if there was an actual person named Kilroy who inspired the graffiti, although there have been claims over the years.

Origin and use of the phrase

The phrase may have originated through United States servicemen who would draw the doodle and the text "Kilroy was here" on the walls and other places where they were stationed, encamped, or visited. An ad in Life magazine noted that WWII-era servicemen were fond of claiming that "whatever beach-head they stormed, they always found notices chalked up ahead of them, that 'Kilroy was here'".[3] Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable notes that it was particularly associated with the Air Transport Command, at least when observed in the United Kingdom.[4] At some point, the graffiti (Chad) and slogan (Kilroy was here) must have merged.[5]

Many sources claim origin as early as 1939.[2][6][7] An early example of the phrase may date from 1937, before World War II. The US History Channel broadcast Fort Knox: Secrets Revealed in 2007 included a shot of a chalked "KILROY WAS HERE" dated 1937-05-13. Fort Knox's vault was loaded in 1937 and inaccessible until the 1970s, when an audit was carried out and the footage was shot.[8] However, historian Paul Urbahns was involved in the production of the program, and he says that the footage was a reconstruction.[9]

According to one story, German intelligence found the phrase on captured American equipment. This led Adolf Hitler to believe that Kilroy could be the name or codename of a high-level Allied spy. At the time of the Potsdam Conference in 1945, it was rumored that Stalin found "Kilroy was here" written in the VIP bathroom, prompting him to ask his aides who Kilroy was.[1][10] War photographer Robert Capa noted a use of the phrase at Bastogne in December 1944: "On the black, charred walls of an abandoned barn, scrawled in white chalk, was the legend of McAuliffe's GIs: KILROY WAS STUCK HERE."[11]

Foo was here

The phrase "Foo was here" was used from 1941–45 as the Australian equivalent of "Kilroy was here". "Foo" was thought of as a gremlin by the Royal Australian Air Force, and the name may have been derived from the 1930s cartoon Smokey Stover in which the character used the word "foo" when he could not remember the name of something.[12] It has been claimed that Foo came from the acronym for Forward Observation Officer, but this is unlikely.[13]

Real Kilroys

The Oxford English Dictionary says simply that Kilroy was "the name of a mythical person".[5] One theory identifies James J. Kilroy (1902–1962) as the man behind the signature,[14] an American shipyard inspector.[5] The New York Times indicated J.J. Kilroy as the origin in 1946, based on the results of a contest conducted by the American Transit Association[7][15] to establish the origin of the phenomenon.[16] The article noted that Kilroy had marked the ships as they were being built as a way to be sure that he had inspected a compartment, and the phrase would be found chalked in places that nobody could have reached for graffiti, such as inside sealed hull spaces.[15] Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable notes this as a possible origin, but suggests that "the phrase grew by accident."[4]

The Lowell Sun reported in November 1945 that Sgt. Francis J. Kilroy, Jr. from Everett, Massachusetts wrote "Kilroy will be here next week" on a barracks bulletin board at a Boca Raton, Florida airbase while ill with flu, and the phrase was picked up by other airmen and quickly spread abroad.[8] The Associated Press similarly reported Sgt. Kilroy's account of being hospitalized early in World War II, and his friend Sgt. James Maloney wrote the phrase on a bulletin board. Maloney continued to write the shortened phrase when he was shipped out a month later, according to the AP account, and other airmen soon picked it up. Francis Kilroy only wrote the phrase a couple of times.[5][17]

Chad

The figure was initially known in the United Kingdom as "Mr Chad" and would appear with the slogan "Wot, no sugar" or a similar phrase bemoaning shortages and rationing.[1][18] He often appeared with a single curling hair that resembled a question mark and with crosses in his eyes.[19] The phrase "Wot, no —?" pre-dates "Chad" and was widely used separately from the doodle.[8] Chad was used by the RAF and civilians; he was known in the Army as Private Snoops, and in the Navy he was called The Watcher.[20] Chad might have first been drawn by British cartoonist George Edward Chatterton in 1938. Chatterton was nicknamed "Chat", which may then have become "Chad."[1] Life Magazine wrote in 1946 that the RAF and Army were competing to claim him as their own invention, but they agreed that he had first appeared around 1944.[19] The character resembles Alice the Goon, a character in Popeye who first appeared in 1933,;[21] and another name for Chad was "The Goon".[19]

A spokesman for the Royal Air Force Museum London suggested in 1977 that Chad was probably an adaptation of the Greek letter Omega, used as the symbol for electrical resistance; his creator was probably an electrician in a ground crew.[22] Life suggested that Chad originated with REME, and noted that a symbol for alternating current resembles Chad (a sine wave through a straight line), that the plus and minus signs in his eyes represent polarity, and that his fingers are symbols of electrical resistors.[19] The character is usually drawn in Australia with pluses and minuses as eyes and the nose and eyes resemble a distorted sine wave.[21] The Guardian suggested in 2000 that "Mr. Chad" was based on a diagram representing an electrical circuit. One correspondent said that a man named Dickie Lyle was at RAF Yatesbury in 1941, and he drew a version of the diagram as a face when the instructor had left the room and wrote "Wot, no leave?" beneath it.[23] This idea was repeated in a submission to the BBC in 2005 which included a story of a 1941 radar lecturer in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire who drew the circuit diagram with the words "WOT! No electrons?"[18] The RAF Cranwell Apprentices Association says that the image came from a diagram of how to approximate a square wave using sine waves, also at RAF Yatesbury and with an instructor named Chadwick. This version was initially called Domie or Doomie,[24] and Life noted that Doomie was used by the RAF.[19] REME claimed that the name came from their training school, nicknamed "Chad's Temple"; the RAF claimed that it arose from Chadwick House at a Lancashire radio school; and the Desert Rats claimed that it came from an officer in El Alamein.[19]

It is unclear how Chad gained widespread popularity or became conflated with Kilroy. It was, however, widely in use by the late part of the war and in the immediate post-war years, with slogans ranging from the simple "What, no bread?" or "Wot, no char?" to the plaintive; one sighting was on the side of a British 1st Airborne Division glider in Operation Market Garden with the complaint "Wot, no engines?" The Los Angeles Times reported in 1946 that Chad was "the No. 1 doodle", noting his appearance on a wall in the Houses of Parliament after the 1945 Labour election victory, with "Wot, no Tories?"[25] Trains in Austria in 1946 featured Mr. Chad along with the phrase "Wot—no Fuehrer?"[26]

As rationing became less common, so did the joke. The cartoon is occasionally sighted today as "Kilroy was here",[8] but "Chad" and his complaints have long fallen from popular use, although they continue to be seen occasionally on walls and in references in popular culture.

Smoe

Writing about the Kilroy phenomenon in 1946, The Milwaukee Journal describes the doodle as the European counterpart to "Kilroy was here", under the name Smoe. It also says that Smoe was called Clem in the African theater.[27] It noted that next to "Kilroy was here" was often added "And so was Smoe". While Kilroy enjoyed a resurgence of interest after the war due to radio shows and comic writers, the name Smoe had already disappeared by the end of 1946.[28] A B-24 airman writing in 1998 also noted the distinction between the character of Smoe and Kilroy (who he says was never pictured), and suggested that Smoe stood for "Sad men of Europe".[29] Correspondents to Life magazine in 1962 also insisted that Clem, Mr. Chad or Luke the Spook was the name of the figure, and that Kilroy was unpictured. The editor suggested that the names were all synonymous early in the war, then later separated into separate characters.[30]

Other names

Similar drawings appear in many countries. Herbie (Canada), Overby (Los Angeles, late 1960s),[31] Flywheel, Private Snoops, The Jeep, and Clem (Canada) are alternative names.[1][2][32] An advertisement in Billboard in November 1946 for plastic "Kilroys" also used the names Clem, Heffinger, Luke the Spook, Some, and Stinkie.[33] "Luke the Spook" was the name of a B-29 bomber, and its nose-art resembles the doodle and is said to have been created at the Boeing factory in Seattle.[34] In Chile, the graphic is known as a "sapo"[32] (slang for nosy).

In Poland, Kilroy is replaced with "Józef Tkaczuk", "Robert Motherwell", or "M. Pulina".[32] In Russia, the phrase "Vasya was here" (Russian: Здесь был Вася) is a notorious piece of graffiti.[35]

In popular culture

Kilroy has been seen in a number of television series and films including Hogan's Heroes (on the wall in "The Cooler"), American Dad!, Doctor Who, Flushed Away, Fringe, Futurama, Total Drama Island, Home Improvement, Kelly's Heroes, M*A*S*H, The New Avengers, Taken, Popeye the Sailor, Looney Tunes and Seinfeld; in the video games Halo 3, Brothers in Arms: Hell's Highway, Fallout: New Vegas, Payday 2, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Dino D-Day, Skate 3, Everybody's Gone to the Rapture, War Thunder, Mega Man Legends 2, Counter Strike: Source, and Call of Duty: WWII,[36] the computer game Chronomaster, and in the animated series Adventure Time, in the episode ″Too Old″, as Finn the Human's signature.[37] Additionally:

- In September 1946, Enterprise Records released a song by NBC singer Paul Page titled "Kilroy Was Here."[38]

- Peter Viereck wrote a poem, published in 1948, about the ubiquitous Kilroy, writing that "God is like Kilroy. He, too, Sees it all."[32]

- In the 1948 film I Love Trouble detective Stuart Bailey writes "Killroy Was Here" on a pillow next to a sleeping girl.[39]

- In a Peanuts comic, Lucy claims her grandmother was one of the first to scrawl the doodle in a lady's room. In another comic, Snoopy scrawls the doodle on a sheet of paper left on a desk.[40] This is one of many World War II references made in the strip.

- Isaac Asimov's short story "The Message" (1955) depicts a time-travelling George Kilroy from the 30th Century as the writer of the graffiti.[32]

- Kilroy is mentioned in the following rhyme, published in A Diller, a Dollar: Rhymes and Sayings For the Ten O’clock Scholar (1955), compiled by Lillian Morrison:[5]

Clap my hands and jump for joy;

I was here before Kilroy.

Sorry to spoil your little joke;

I was here, but my pencil broke.

- — Kilroy

- Thomas Pynchon's novel V. (1963) includes the proposal that the Kilroy doodle originated from a band-pass filter diagram.[41]

- On December 25th, 1968, a parody of "'Twas the Night Before Christmas" written by Ken Young was transmitted to Apollo 8 that featured the lines "When what to his wondering eyes should appear, but a Burma Shave sign saying, "Kilroy was here." [42]

- The Kilroy's bar chain, popular with Indiana University students in Bloomington, Indiana, was founded in 1975 by Bill and Linda Prall and is named after and features the likeness of Kilroy.[43]

- The Styx album titled Kilroy Was Here (1983) was certified Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). A Styx song, "Mr. Roboto", ends with the line "I'm Kilroy."[44]

- In 1997, Kilroy was featured on New Zealand stamp #1422 issued on 19 March.[37]

- Ann Packer (author)'s popular novel The Dive From Clausen's Pier (2002) features a character named Kilroy, a nickname derived from "Kilroy Was Here."[45]

- A film based on the graffiti phenomenon started production in June 2017. The film is directed by Kevin Smith and scripted by Smith and Andrew McElfresh.[46] It was originally written as a Krampus feature, but was later rewritten following the 2015 Hollywood horror film of the same name.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shackle, Eric (7 August 2005). "Mr Chad And Kilroy Live Again". Open Writing. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 "What's the origin of "Kilroy was here"?". The Straight Dope. 4 August 2000.

- ↑ Inc, Time (17 May 1948). LIFE. p. 120.

- 1 2 Brewer's: Cassell, 1956. p. 523

- 1 2 3 4 5 Quinion, Michael. "Kilroy was here". World Wide Words. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ Sickels, Robert (2004). "Leisure Activities". The 1940s. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 113. ISBN 9780313312991.

- 1 2 Brown, Jerold E. (2001). "Kilroy". Historical dictionary of the U.S. Army. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 264. ISBN 0-313-29322-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Martin, Gary. "Kilroy was here". Phrases.org.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ↑ "Kilroy Was Here in 1937 . . . Well, not really". "Kilroy Was Here" Sightings page 4. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon L.: FUBAR: Soldier Slang of World War II ISBN 978-1-84603-175-5

- ↑ Capa, Robert (1947). Slightly Out of Focus. Henry Holt and Co.

- ↑ Patridge, Eric; Beale, Paul (1986). A dictionary of catch phrases: British and American, from the sixteenth century to the present day. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 0-415-05916-X.

- ↑ "foo". The Jargon File 4.4.7. 29 December 2003. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ James J. Kilroy at Find a Grave

- 1 2 "Transit Association Ships a Street Car To Shelter Family of 'Kilroy Was Here'", The New York Times, 24 December 1946.

- ↑ "Kilroy Was Here". In Transit. Amalgamated Transit Union. 54-55: 14. 1946.

- ↑ Associated Press (14 November 1945). ""Kilroy" Mystery is Finally Solved". The Lewiston Daily Sun.

- 1 2 "WW2 People's War – Mr. CHAD". BBC. 24 January 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reeve, Elizabeth (18 March 1946). "Wot! Chad's Here". Life Magazine. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Partridge, Eric; Beale, Paul (2002). A dictionary of slang and unconventional English: colloquialisms and catch phrases, fossilised jokes and puns, general nicknames, vulgarisms and such Americanisms as have been naturalised (8 ed.). Routledge. p. 194. ISBN 0-415-29189-5.

- 1 2 Zakia, Richard D. (2002). Perception and imaging. Focal Press. p. 245. ISBN 0-240-80466-X.

- ↑ "Changing Patterns in World Graffiti". Ludington Daily News. 16 March 1977. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ McKie (Smallweed), David (25 November 2000). "Dimpled and pregnant". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ "Wot no respect?". RAF Related Legends. RAF Cranwell Apprentices Association. 9 December 2009. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Plimer, Denis (1 December 1946). "No. 1 Doodle". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ "Mr. Chad travels". Schenectady Gazette. 12 October 1946. Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ "There Are Places Nobody Ever Was Before, but Look, Kilroy Was There". The Milwaukee Journal. 28 November 1946. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ "Once Honorably Discharged, Kilroy is Here, but No Smoe". The Milwaukee Journal. 9 December 1946. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, John Laurence (1998). The forbidden diary: a B-24 navigator remembers. McGraw-Hill. p. 45. ISBN 0-07-158187-1.

- ↑ "Letters to the Editor: Miscellany". Life Magazine. 16 November 1962. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ Nelson, Harry (11 September 1966). "Wall writers turn away from big-nosed favorite of World War II: Kilroy Was Here, but Oger and Overby Take Over". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dziatkiewicz, Łukasz (4 November 2009). "Kilroy tu był". Polityka (in Polish). Retrieved 13 June 2010.

- ↑ Chas. Demee MFG. Co. (9 November 1946). "At last Kilroy is here (advert)". Billboard. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ "American notes & queries: a journal for the curious". 5–6. 1945.

- ↑ Palveleva, Lily (24 March 2008). Ключевое слово: "граффити". Радио Свобода (in Russian). Retrieved 30 August 2010.

- ↑ "r/WWII - Bringing back an old WW2 meme". reddit.

- 1 2 Melvin, Morris (January 2007). "Kilroy Was Here--On Stamps". U.S. Stamp News. 13 (1): 30. ISSN 1082-9423.

- ↑ "Record Reviews". Billboard. 14 September 1946. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ ClassicFilmTheater (2012-10-17), I Love Trouble (1948), retrieved 2016-08-31

- ↑ http://www.peanuts.com/wp-content/comic-strip/color-low-resolution/desktop/2014/daily/pe_c140425.jpg

- ↑ Ascari, Maurizio; Corrado, Adriana (2006). Sites of exchange: European crossroads and faultlines. Internationale Forschungen zur allgemeinen und vergleichenden Literaturwissenschaft. 103. Rodopi. p. 211. ISBN 90-420-2015-6.

- ↑ Go, Flight! The Unsung Heroes of Mission Control. p. 133.

- ↑ "Bloomington's Kilroy's opening downtown Indianapolis outpost". Retrieved 2018-01-02.

- ↑ Recording Industry Association of America. "Gold and Platinum Searchable Database". RIAA. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (11 April 2002). "Books of the Times; Off the Deep End Without Getting Wet". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Giroux, Jack (June 15, 2017). "Kevin Smith’s Monster Movie ‘Killroy Was Here’ Begins Filming At A Florida College". /Film.

Further reading

- Kilroy, James J. of Halifax, Massachusetts (12 January 1947). "Who Is 'Kilroy'?". The New York Times Magazine: 30.

- Walker, Raymond J. (July 1968). "Kilroy was here. A history of scribbling in ancient and modern times". Hobbies - the Magazine for Collectors. 73: 98N–98O. ISSN 0018-2907.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kilroy was here. |

- The Legends of "Kilroy Was Here" by Patrick Tillery

- "What's the origin of 'Kilroy was here'?", The Straight Dope

- On the legend from snopes.com

- Chad drawn in an army album from 21 June 1944 by Ron Goldstein, with the caption "Wot! Leave again?" The album is now held at the Imperial War Museum.