Kepler's Supernova

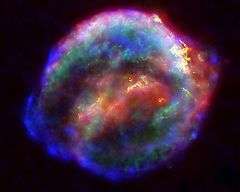

A false-color composite (CXO/HST/Spitzer Space Telescope) image of the supernova remnant nebula from SN 1604. Credit: NASA/ESA/JHU/R. Sankrit & W. Blair | |

| Other designations | 1ES 1727-21.4 |

|---|---|

| Event type |

Star, supernova |

| Spectral class | Ia [1][2] |

| Date | 8–9 October 1604 |

| Constellation |

Ophiuchus |

| Right ascension | 17h 30m 42s |

| Declination | −21° 29′ |

| Epoch | J2000 |

| Galactic coordinates | G4.5+6.8 |

| Distance | 20,000 light-years (6.1 kpc) |

| Remnant | Shell |

| Host | Milky Way |

| Progenitor | White Dwarf-RedGiant double star system |

| Progenitor type | Type Ia supernova |

| Colour (B-V) | Unknown |

| Notable features |

Latest observed supernova in our galaxy. Maintained naked-eye visibility for 18 months. |

| Peak apparent magnitude | −2.25 to −2.5 |

| Preceded by | SN 1572 |

| Followed by | Cassiopeia A (unobserved, c. 1680), G1.9+0.3 (unobserved, c. 1868), SN 1885A (next observed) |

|

| |

SN 1604, also known as Kepler's Supernova, Kepler's Nova or Kepler's Star, was a supernova of Type Ia[1][2] that occurred in the Milky Way, in the constellation Ophiuchus. Appearing in 1604, it is the most recent supernova in our own galaxy to have been unquestionably observed by the naked eye,[3] occurring no farther than 6 kiloparsecs or about 20,000 light-years from Earth.

Observation

Visible to the naked eye, Kepler's Star was brighter at its peak than any other star in the night sky, with an apparent magnitude of −2.5. It was visible during the day for over three weeks. Records of its sighting exist in European, Chinese, Korean and Arabic sources.[4][5]

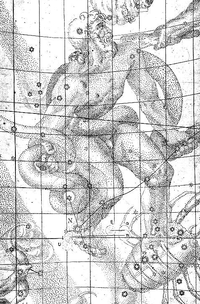

Johannes Kepler's original drawing from De Stella Nova (1606) depicting the location of the stella nova, marked with an N (8 grid squares down, 4 over from the left) |

It was the second supernova to be observed in a generation (after SN 1572 seen by Tycho Brahe in Cassiopeia). No further supernovae have since been observed with certainty in the Milky Way, though many others outside our galaxy have been seen since S Andromedae in 1885. SN 1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud was easily visible to the naked eye.

Evidence exists for two Milky Way supernovae whose signals would have reached Earth c. 1680 and 1870 — Cassiopeia A, and G1.9+0.3 respectively. There is no historical record of either having been detected in those years probably as absorption by interstellar dust made them fainter.[6]

The supernova remnant resulting from Kepler's supernova is considered to be one of the prototypical objects of its kind and is still an object of much study in astronomy.

Controversies in Europe

Johannes Kepler, along with other astronomers of the time, was concerned with observing the conjunction of Mars and Jupiter, which saw in terms of an auspicious conjunction, linked in their minds to the Star of Bethlehem. However cloudy weather prevented him making any celestial observations. Nevertheless, his fellow astronomers Wilhelm Fabry, Michael Maestlin and Helisaeus Roeslin were able to make observations on 9 October, but did not record the supernova.[7] The first recorded observation in Europe was by Lodovico delle Colombe in northern Italy on 9 October 1604.[8] The weather only enabled Kepler to begin observing the luminous display on October 17 while working at the imperial court in Prague for Emperor Rudolf II.[9] It was subsequently named after him, even though he was not its first observer, as his observations tracked the object for an entire year and because of his book on the subject, entitled De Stella nova in pede Serpentarii ("On the new star in Ophiuchus's foot", Prague 1606).

Delle Colombe-Galileo controversy

Delle Colombe went on to publish Discourse of Lodovico delle Colombe in which he shows that the Star Newly Appeared in October 1604 is neither a Comet nor a New Star in 1606 where he defended an aristotelian view of Cosmology which was then sharply challenged by Galileo Galilei.

Kepler-Roeslin controversy

In Kepler's De Stella Nova (1606) concerning this supernova Kepler criticised Roeslin. He argued that in his astrological prognostications, Roeslin had picked out just the two comets, the Great Comet of 1556 and 1580. Roeslin responded in 1609 that this was indeed what he had done. When Kepler replied later that year, he simply observed that by including a broader range of data Roeslin could have made a better argument.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Chandra X-Ray Observatory". Kepler's Supernova Remnant: A Star's Death Comes to Life. Retrieved 2006-01-16.

- 1 2 Reynolds, S. P.; Borkowski, K. J.; Hwang, U.; Hughes, J. P.; Badenes, C.; Laming, J. M.; Blondin, J. M. (2007-10-02). "A Deep Chandra Observation of Kepler's Supernova Remnant: A Type Ia Event with Circumstellar Interaction". The Astrophysical Journal. 668 (2): L135–L138. arXiv:0708.3858. Bibcode:2007ApJ...668L.135R. doi:10.1086/522830.

- ↑ "Kepler's Supernova: Recently Observed Supernova". Universe for Facts. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ Stephenson, F. Richard & Green, David A., Historical Supernovae and their Remnants, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 2002, pp. 60–71.

- ↑ Neuhäuser, Ralph; Rada, Wafiq; Kunitzsch, Paul; Neuhäuser, Dagmar L. (2016). "Arabic Reports about Supernovae 1604 and 1572 in Rawḥ al-Rūḥ by cĪsā b. Luṭf Allāh from Yemen". Journal for the History of Astronomy. 47 (4): 359–374. Bibcode:2016JHA....47..359N. doi:10.1177/0021828616669894. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ↑ "Chandra X-Ray Observatory". Discovery of Most Recent Supernova in Our Galaxy, May 14, 2008. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ↑ Burke-Gaffney, W. (1937). "Kelper and the Star of Bethlehem" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 31: 417–425. Bibcode:1937JRASC..31..417B. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ↑ Delle Colombe L., Discorso di Lodovico Delle Colombe nel quale si dimostra che la nuova Stella apparita l’Ottobre passato 1604 nel Sagittario non è Cometa, ne stella generata, ò creata di nuovo, ne apparente: ma una di quelle che furono da principio nel cielo; e ciò esser conforme alla vera Filosofia, Teologia, e Astronomiche dimostrazioni, Firenze, Giunti, 1606.

- ↑ "Bill Blair's Kepler's Supernova Remnant Page". Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ↑ Fritz, Gerd. "Dialogical Structures in 17th Century Controversies" (PDF). www.festschrift-gerd-fritz.de. Gerd fritz. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

Further reading

- Blair, William P.; Long, Knox S.; Vancura, Olaf (1991). "A detailed optical study of Kepler's supernova remnant". Astrophysical Journal. 366: 484–494. Bibcode:1991ApJ...366..484B. doi:10.1086/169583.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kepler's Supernova. |

- "SN1604". spider@SEDS. Archived from the original on 2013-10-17. Retrieved 2014-10-16.