Kate Chopin

| Kate Chopin | |

|---|---|

Chopin in 1894 | |

| Born |

Katherine O'Flaherty February 8, 1850 St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died |

August 22, 1904 (aged 54) St. Louis, Missouri, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer |

| Genre | Realistic fiction |

| Notable works | The Awakening |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 6 |

Kate Chopin (/ˈʃoʊpæn/;[1] born Katherine O'Flaherty; February 8, 1850 – August 22, 1904), was an American author of short stories and novels based in Louisiana. She is now considered by some scholars[2] to have been a forerunner of American 20th-century feminist authors of Southern or Catholic background, such as Zelda Fitzgerald.

Of maternal French and paternal Irish descent, Chopin was born in St. Louis, Missouri. She married and moved with her husband to New Orleans. They later lived in the country in Cloutierville, Louisiana. From 1892 to 1895, Chopin wrote short stories for both children and adults that were published in such national magazines as Atlantic Monthly, Vogue, The Century Magazine, and The Youth's Companion. Her stories aroused controversy because of her subjects and her approach; they were condemned as immoral by some critics.

Her major works were two short story collections: Bayou Folk (1894) and A Night in Acadie (1897). Her important short stories included "Désirée's Baby" (1893), a tale of miscegenation in antebellum Louisiana,[3] "The Story of an Hour" (1894),[4] and "The Storm" (1898).[3] "The Storm" is a sequel to "At the Cadian Ball," which appeared in her first collection of short stories, Bayou Folk.[3]

Chopin also wrote two novels: At Fault (1890) and The Awakening (1899), which are set in New Orleans and Grand Isle, respectively. The characters in her stories are usually residents of Louisiana. Many of her works are set in Natchitoches in north central Louisiana, a region where she lived.

Within a decade of her death, Chopin was widely recognized as one of the leading writers of her time.[5] In 1915, Fred Lewis Pattee wrote, "some of [Chopin's] work is equal to the best that has been produced in France or even in America. [She displayed] what may be described as a native aptitude for narration amounting almost to genius."[5]

Life

Chopin was born Katherine O'Flaherty in St. Louis, Missouri. Her father, Thomas O'Flaherty, was a successful businessman who had immigrated to the United States from Galway, Ireland. Her mother, Eliza Faris, was his second wife and a well-connected member of the ethnic French community in St. Louis; she was the daughter of Athénaïse Charleville, who was of French Canadian descent. Some of Chopin's ancestors were among the first European (French) inhabitants of Dauphin Island, Alabama.[6]

Kate was the third of five children, but her sisters died in infancy and her half-brothers (from her father's first marriage) died in their early twenties. They were reared Roman Catholic, in the French and Irish traditions. After her father's death in 1855, Chopin developed a close relationship with her mother, maternal grandmother, and great-grandmother. She also became an avid reader of fairy tales, poetry, and religious allegories, as well as classic and contemporary novels. She graduated from Sacred Heart Convent in St. Louis in 1868.[6]

In St. Louis, Missouri, on 8 June 1870,[7] she married Oscar Chopin and settled with him in his home town of New Orleans, an important port. Chopin had six children between 1871 and 1879: in order of birth, Jean Baptiste, Oscar Charles, George Francis, Frederick, Felix Andrew, and Lélia (baptized Marie Laïza).[8] In 1879, Oscar Chopin's cotton brokerage failed.

The family left the city and moved to Cloutierville in south Natchitoches Parish to manage several small plantations and a general store. They became active in the community, and Chopin absorbed much material for her future writing, especially regarding the culture of the Creoles of color of the area.

When Oscar Chopin died in 1882, he left Kate with $42,000 in debt (approximately $420,000 in 2009 money). According to Emily Toth, "for a while the widow Kate ran his [Oscar's] business and flirted outrageously with local men; (she even engaged in a relationship with a married farmer)."[9] Although Chopin worked to make her late husband's plantation and general store succeed, two years later she sold her Louisiana business.[9][10]

Her mother had implored her to move back to St. Louis, and Chopin did, aided by her mother's assistance with finances. Her children gradually settled into life in the bustling city of St. Louis. The following year, Chopin's mother died.[10]

Chopin struggled with depression after the losses in a short time of both her husband and her mother. Her obstetrician and family friend, Dr. Frederick Kolbenheyer, suggested that she start writing, believing that it could be a source of therapeutic healing for her. He understood also that writing could be a focus for her extraordinary energy, as well as a source of income.[11]

By the early 1890s, Kate Chopin began writing short stories, articles, and translations which were published in periodicals, including the St. Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper. She was quite successful and placed many of her publications in literary magazines. At the time, she was considered only as a regional local color writer, as this was a period of considerable publishing of folk tales, works in dialect, and other elements of Southern folk life. Chopin's strong literary qualities were overlooked.[12]

In 1899, her second novel, The Awakening, was published. It generated a significant amount of negative press because its characters, especially the women, behaved in ways that conflicted with current standards of acceptable ladylike behavior. People considered offensive Chopin's treatment of female sexuality, her questions about the virtues of motherhood, and showing occasions of marital infidelity.[13] At the same time, some newspaper critics reviewed it favorably.[14]

This, her best-known work, is the story of a woman trapped in the confines of an oppressive society. It was out of print for several decades, as literary tastes changed. Rediscovered in the 1970s, when there was a wave of new studies and appreciation of women's writings, the novel has since been reprinted and is widely available. It has been critically acclaimed for its writing quality and importance as an early feminist work of the South.[12]

Critics suggest that such works as The Awakening, were too far ahead of their time and therefore not socially embraced. After almost 12 years of publishing and shattered by the lack of acceptance, Chopin, deeply discouraged by the criticism, turned to short story writing.[12] In 1900, she wrote "The Gentleman from New Orleans." That same year she was listed in the first edition of Marquis Who's Who. However, she never made much money from her writing, and had to depend on her investments in Louisiana and St. Louis (aided by her inheritance from her mother) to support her.[12]

While visiting the St. Louis World's Fair on August 20, 1904, Chopin suffered a brain hemorrhage. She died two days later, at the age of 54. She was interred in Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis.[12]

Literary themes

Kate Chopin lived in a variety of locations, based on different economies and societies. These were sources of insights and observations from which she analyzed and expressed her ideas about late 19th-century Southern American society. She was brought up by women who were primarily ethnic French. Living in areas influenced by the Louisiana Creole and Cajun cultures after she joined her husband in Louisiana, she based many of her stories and sketches in her life in Louisiana. They expressed her unusual portrayals (for the time) of women as individuals with separate wants and needs.[10]

Chopin's writing style was influenced by her admiration of the contemporary French writer Guy de Maupassant, known for his short stories:

...I read his stories and marveled at them. Here was life, not fiction; for where were the plots, the old fashioned mechanism and stage trapping that in a vague, unthinkable way I had fancied were essential to the art of story making. Here was a man who had escaped from tradition and authority, who had entered into himself and looked out upon life through his own being and with his own eyes; and who, in a direct and simple way, told us what he saw...[15]

Chopin went beyond Maupassant's technique and style to give her writing its own flavor. She had an ability to perceive life and creatively express it. She concentrated on women's lives and their continual struggles to create an identity of their own within the Southern society of the late nineteenth century. For instance, in "The Story of an Hour," Mrs. Mallard allows herself time to reflect after learning of her husband's death. Instead of dreading the lonely years ahead, she stumbles upon another realization altogether.

She knew that she would weep again when she saw the kind, tender hands folded in death; the face that had never looked save with love upon her, fixed and gray and dead. But she saw beyond that bitter moment a long procession of years to come that would belong to her absolutely. And she opened and spread her arms out to them in welcome.[4]

Not many writers during the mid- to late 19th century were bold enough to address subjects that Chopin took on. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, of Emory University, wrote that "Kate was neither a feminist nor a suffragist, she said so. She was nonetheless a woman who took women extremely seriously. She never doubted women's ability to be strong."[16] Kate Chopin's sympathies lay with the individual in the context of his and her personal life and society.

Through her stories, Kate Chopin wrote a kind of autobiography and described her societies; she had grown up in a time when her surroundings included the abolitionist movements before the American Civil War, and their influence on freedmen education and rights afterward, as well as the emergence of feminism. Her ideas and descriptions were not reporting, but her stories expressed the reality of her world.[10]

Chopin took strong interest in her surroundings and wrote about many of her observations. Jane Le Marquand assesses Chopin's writings as a new feminist voice, while other intellectuals recognize it as the voice of an individual who happens to be a woman. Marquand writes, "Chopin undermines patriarchy by endowing the Other, the woman, with an individual identity and a sense of self, a sense of self to which the letters she leaves behind give voice. The 'official' version of her life, that constructed by the men around her, is challenged and overthrown by the woman of the story."[15]

Chopin appeared to express her belief in the strength of women. Marquand draws from theories about creative nonfiction in terms of her work. In order for a story to be autobiographical, or even biographical, Marquand writes, there has to be a nonfictional element, but more often than not the author exaggerates the truth to spark and hold interest for the readers. Kate Chopin might have been surprised to know her work has been characterized as feminist in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, just as she had been in her own time to have it described as immoral. Critics tend to regard writers as individuals with larger points of view addressed to factions in society.[15]

The short story of "Désirée's Baby" focuses on Kate Chopin's experience with miscegenation and communities of the Creoles of color in Louisiana. She came of age when slavery was institutionalized in St. Louis and the South. In Louisiana, there had been communities established of free people of color, especially in New Orleans, where formal arrangements were made between white men and free women of color or enslaved women for plaçage, a kind of common-law marriage. There and in the country, she lived with a society based on the history of slavery and the continuation of plantation life, to a great extent. Mixed-race people (also known as mulattos) were numerous in New Orleans and the South. This story addresses the racism of 19th century America; persons who were visibly European-American could be threatened by the revelation of also having African ancestry. Chopin was not afraid to address such issues, which were often suppressed and intentionally ignored. Her character Armand tries to deny this reality, when he refuses to believe that he is of black descent, as it threatens his ideas about himself and his status in life. R. R. Foy believed that Chopin's story reached the level of great fiction, in which the only true subject is "human existence in its subtle, complex, true meaning, stripped of the view with which ethical and conventional standards have draped it".[17]

"Desiree's Baby" was first published in an 1893 issue of Vogue magazine, alongside another of Kate Chopin's short stories, "A Visit to Avoyelles", under the heading "Character Studies: The Father of Desiree's Baby - The Lover of Mentine." "A Visit to Avoyelles" typifies the local color writing that Chopin was known for, and is one of her stories that shows a couple in a completely fulfilled marriage. While Doudouce is hoping otherwise, he sees ample evidence that Mentine and Jules' marriage is a happy and fulfilling one, despite the poverty-stricken circumstances that they live in. In contrast, in "Desiree's Baby", which is much more controversial, due to the topic of miscegenation, portrays a marriage in trouble. The other contrasts to "A Visit to Avoyelles" are very clear, although some are more subtle than others. Unlike Mentine and Jules, Armand and Desiree are rich and own slaves and a plantation. Mentine and Jules' marriage has weathered many hard times, while Armand and Desiree's falls apart at the first sign of trouble. Kate Chopin was very talented at showing various sides of marriages and local people and their lives, making her writing very broad and sweeping in topic, even as she had many common themes in her work.[18][19]

Representation in other media

Louisiana Public Broadcasting, under president Beth Courtney, produced a documentary on Chopin's life, Kate Chopin: A Reawakening.[20]

In the penultimate episode of the first season of HBO's Treme, set in New Orleans, the teacher Creighton (played by John Goodman) assigns Kate Chopin's The Awakening to his freshmen and warns them:

I want you to take your time with it," he cautions. "Pay attention to the language itself. The ideas. Don't think in terms of a beginning and an end. Because unlike some plot-driven entertainments, there is no closure in real life. Not really.[21]

Works

- "Bayou Folk" Read "Bayou Folk"

- "A Night in Acadie" Read "A Night in Acadie"

- "At the Cadian Ball" (1892) Read "At the Cadian Ball"

- "Désirée's Baby" (1895) Read "Désirée's Baby"

- "The Story of an Hour" (1896) Read "The Story of an Hour"

- "Emancipation: A Life Fable" Read "Emancipation: A Life Fable"

- "The Storm" (1898) Read "The Storm"

- "A Pair of Silk Stockings" Read "A Pair of Silk Stockings"

- "The Locket"

- "Athenaise" Read "Athenaise"

- "Lilacs" Read "Lilacs"

- "A Respectable Woman" Read "A Respectable Woman"

- "The Unexpected" Read "The Unexpected"

- "The Kiss" Read "The Kiss"

- "Beyond the Bayou" Read "Beyond the Bayou"

- "An No-Account Creole" Read "An No-Account Creole"

- "Fedora"

- "Regret" Read "Regret"

- "Madame Célestin's Divorce" Read "Madame Célestin's Divorce"

- At Fault (1890), Nixon Jones Printing Co, St. Louis Read "At Fault"

- The Awakening (1899), H.S. Stone, Chicago Read "The Awakening"

Honors and awards

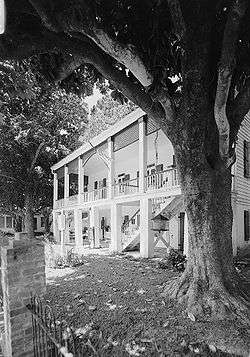

- Her home with Oscar Chopin in Cloutierville was built by Alexis Cloutier in the early part of the 19th century. In the late 20th century, the house was designated as the Kate Chopin House, a National Historic Landmark (NHL), because of her literary significance. The house was adapted for use as the Bayou Folk Museum. On October 1, 2008, the house was destroyed by a fire, with little left but the chimney.[22]

- In 1990 Chopin was honored with a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame in that city in Missouri.[23]

- In 2012 she was commemorated with an iron bust of her head at the Writer's Corner in the Central West End neighborhood of St. Louis, across the street from Left Bank Books.[24]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Chopin, Kate | Definition of Chopin, Kate in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 2018-02-16.

- ↑ Nilsen, Helge Normann. "American Women's Literature in the Twentieth Century: A Survey of Some Feminist Trends," American Studies in Scandinavia, Vol. 22, 1990, pp. 27-29; University of Trondheim

- 1 2 3 William L. (Ed.) Andrews, Hobson, Trudier Harris, Minrose C. Gwwin (1997). The Literature of the American South: A Norton Anthology. Norton, W. W. & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31671-1.

- 1 2 Chopin, Kate. The Story of an Hour.

- 1 2 Fred Lewis Pattee. A History of American Literature Since 1870. Harvard University Press. p. 364.

- 1 2 Literary St. Louis: Noted Authors and St. Louis Landmarks Associated With Them. Associates of St. Louis University Libraries, Inc. and Landmarks Associate of St. Louis, Inc. 1969.

- ↑ Marriage certificate between Oscar Chopin and Katie O'Flaherty accessed on ancestry.com on 19 October 2015

- ↑ "Biography". www.katechopin.org. Retrieved 2015-12-11.

- 1 2 Toth, Emily (1990). "Reviews the essay "The Shadows of the First Biographer: The Case of Kate Chopin"". Southern Review (26).

- 1 2 3 4 "Short Story Criticism 'An Introduction to Kate Chopin 1851-1904'". Short Story Criticism. 116. 2008.

- ↑ Seyersted, Per (1985). Kate Chopin: A Critical Biography. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State UP. ISBN 0-8071-0678-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 O'Flaherty (1984). "'Kate Chopin, An Introduction to (1851-1904)'". Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism. 14.

- ↑ Walker, Nancy (2001). Kate Chopin: A Literary Life. Palgrave Publishers.

- ↑ Toth, Emily (1990). Kate Chopin. William Morrow & Company, Inc.

- 1 2 3 Le Marquand, Jane. "Kate Chopin as Feminist: Subverting the French Androcentric Influence". Deep South 2 (1996)

- ↑ Kate Chopin: A Re-Awakening. "Interview: Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Emory University". 14 March 2008

- ↑ Foy, R.R. (1991). "Chopin's Desiree's Baby". Explicatory (49). pp. 222–224.

- ↑ Gibert, Teresa "Textual, Contextual and Critical Surprises in 'Desiree's Baby'" Connotations: A Journal for Critical Debate. vol. 14.1-3. 2004/2005. pg. 38-67

- ↑ Chopin, Kate "A Visit to Avoyelles" Bayou Folk 1893 pg. 223-229

- ↑ "Kate Chopin: A Re-Awakening - About the Program". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ "Treme - as a season ends, so does a life", The Atlantic, June 2010, accessed 25 June 2014

- ↑ Welborn, Vickie (1888-10-01). "Loss of Kate Chopin House to fire 'devastating'". The Town Talk.

- ↑ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ↑ "Kate Chopin Bust Unveiled". West End Word. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

Further reading

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Kate Chopin |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Kate Chopin |

- "Kate O'Flaherty Chopin" (1988) A Dictionary of Louisiana Biography, Vol. I, p. 176

- Koloski, Bernard (2009) Awakenings: The Story of the Kate Chopin Revival. Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, LA. ISBN 978-0-8071-3495-5

- Eliot, Lorraine Nye (2002) The Real Kate Chopin, Dorrance Publishing Co., Pittsburgh, PA. ISBN 0-8059-5786-3

- Berkove, Lawrence I (2000) "Fatal Self-Assertion in Kate Chopin's 'The Story of an Hour'." American Literary Realism 32.2, pp. 152–158.

- Toth, Emily (1999) Unveiling Kate Chopin. University Press of Mississippi, Jackson, MS. ISBN 1-57806-101-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kate Chopin. |