Karenia brevis

| Karenia brevis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | SAR |

| Phylum: | Dinoflagellata |

| Class: | Dinophyceae |

| Genus: | Karenia |

| Species: | K. brevis |

| Binomial name | |

| Karenia brevis (Davis) G. Hansen et Moestrup | |

Karenia brevis is part of the Karenia (dinoflagellate) genus, a marine dinoflagellate common in Gulf of Mexico waters, and is the organism responsible for the "tides" (coastal infestations) termed red tides that affect Gulf coasts—of Florida and Texas in the U.S., and nearby coasts of Mexico. It is the source organism for various toxins found present during such "tides", including the eponymously named brevetoxins.

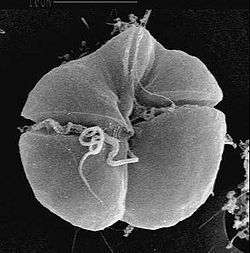

K. brevis is a microscopic, single-celled, photosynthetic organism that can "bloom" (see algal bloom) frequently along Florida, Texas,[1] and Mexican coastal waters. Each cell has two flagella that allow it to move through the water in a spinning motion. K. brevis naturally produces a suite of potent neurotoxins collectively called brevetoxins, which cause gastrointestinal and neurological problems in other organisms and are responsible for large die-offs of marine organisms and seabirds.[2] K. brevis is unarmored, and does not contain peridinin. Cells are between 20 and 40 μm in diameter.

History

Karenia brevis was named for Dr. Karen A. Steidinger[3] in 2001, and was previously known as Gymnodinium breve and Ptychodiscus brevis.

Ecology and distribution

In its normal environment, K. brevis will move in the direction of greater light[4] and against the direction of gravity,[5] which will tend to keep the organism at the surface of whatever body of water it is suspended within. Cells are thought to require photosynthesis to obtain nutrition.[6] Its swimming speed is about one metre per hour.[7] K. brevis is the causative agent of red tide, when K. brevis has grown to very high concentrations and the water can take on a reddish or pinkish coloration. The region around southwest Florida is one of the major hotspots for red tide blooms. Red tide outbreaks have been known to occur since the Spanish explorers of the 15th century. Algal species that have harmful effects on either the environment or human health are commonly known as harmful algal blooms (HABs). HABs are harmful to organisms that share the same habitat as them, though only when in high concentrations.[2]

Detection

Traditional methods for the detection of K. brevis are based on microscopy or pigment analysis. These are time-consuming, and typically require a skilled microscopist for identification.[8] Cultivation-based identification is extremely difficult and can take several months. A molecular, real-time PCR-based approach for sensitive and accurate detection of K. brevis cells in marine environments has therefore been developed.[9] Another technique for the detection of K. brevis is multiwavelength spectroscopy, which uses a model-based examination of UV-vis spectra.[10] Methods of detection using satellite spectroscopy have also been developed.[11][12] This particular protist is known to be harmful to humans, large fish, and other marine mammals. It has been found that the survival of scleractinian coral is negatively affected by brevetoxin. Scleractinian coral exhibits decreased rates of respiration when there is a high concentration of K. brevis.[2]

References

- ↑ "Red Tide FAQ". www.tpwd.state.tx.us. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- 1 2 3 Ross, Cliff; Ritson-Williams, Raphael; Pierce, Richard; Bullington, J. Bradley; Henry, Michael; Paul, Valerie J. (February 2010). "Effects of the Florida Red Tide Dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis, on Oxidative Stress and Metamorphosis of Larvae of the Coral Porites astreoides". Harmful Algae. 9 (2): 173–9. doi:10.1016/j.hal.2009.09.001.

- ↑ "Bay Soundings". baysoundings.com.

- ↑ Geesey, M. E., and P. A. Tester. 1993. Gymnodinium breveGymnodinium breve: ubiquitous in Gulf of Mexico waters, p. 251-256. InIn T. J. S. Smayda and Shimizu (ed.), Toxic phytoplankton blooms in the sea: Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Toxic Marine Phytoplankton. Elsevier Science Publishing, Inc., New York, N.Y.

- ↑ Kamykowski, D.; Milligan, E. J.; Reed, R. E. (1998). "Relationships between geotaxis/phototaxis and diel vertical migration in autotrophic dinoflagellates". J. Plankton Res. 20: 1781–1796. doi:10.1093/plankt/20.9.1781.

- ↑ Aldrich, D. V. (1962). "Photoautotrophy in Gymnodinium breve.Gymnodinium breve". Science. 137: 988–990. doi:10.1126/science.137.3534.988. PMID 17782737.

- ↑ Steidinger, K. A.; Joyce Jr, E. A. (1973). "Florida red tides". State Fla. Dep. Nat. Resour. Educat. Ser. 17: 1–26.

- ↑ Millie, D. F.; Schofield, O. M.; Kirkpatrick, G. J.; Hohnsen, G.; Tester, P. A.; Vinyard, B. T. (1997). "Detection of harmful algal blooms using photopigments and absorption signatures: a case study of the Florida red tide dinoflagellate, Gymnodinium breve. Gymnodinium breve". Limnol. Oceanogr. 42: 1240–1251.

- ↑ Gray, M.; B. Wawrik; E. Caspar & J.H. Paul (2003). "Molecular Detection and Quantification of the Red Tide Dinoflagellate Karenia brevis in the Marine Environment". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (9): 5726–5730. doi:10.1128/AEM.69.9.5726-5730.2003. PMC 194946. PMID 12957971.

- ↑ Spear, H. Adam, K. Daly, D. Huffman, and L. Garcia-Rubio. 2009. Progress in developing a new detection method for the harmful algal bloom species, Karenia brevis, through multiwavelength spectroscopy. HARMFUL ALGAE. 8:189-195.

- ↑ Hu, C., et al. (2005) Red tide detection and tracing using MODIS fluorescence data: A regional example in SW Florida coastal waters, Remote Sensing of Environment 97(2005) 311-321 http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.115.4645&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- ↑ Carvalho, G., et al. (2007) Detection of Florida "red tides" from SeaWiFS and MODIS imagery, Anais XIII Simposio Brasileiro de Sensoriamento Remoto, 21-26 Abril 2007 http://marte.dpi.inpe.br/col/dpi.inpe.br/sbsr@80/2006/11.07.00.35/doc/4581-4588.pdf

Glibert, P.M.; Burkholder, J.M (22 May 2014). "The Complex Relationships Between Increases in Fertilization of the Earth, Coastal Eutrophication and Proliferation of Harmful Algal Blooms". Ecological Studies. 189: 341-354. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-32210-8_26.

Further reading

- Campbell, Lisa; Pepper, Alan E.; Ryan, Darcie E. (11 October 2014). "De novo assembly and characterization of the transcriptome of the toxic dinoflagellate Karenia brevis". BMC Genomics. 15 (888). doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-888. PMC 4203930. PMID 25306556.

- Ryan, Darcie; Pepper, Alan; Campbell, Lisa (11 October 2014). "De novo assembly and characterization of the transcriptome of the toxic dinoflagellate Karenia brevis". BMC Genomics. 15 (1): 888. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-888. PMC 4203930. PMID 25306556.

- Kirkpatrick, Barbara; Kohler, Kate; Byrne, Margaret (15 September 2014). "Human responses to Florida red tides: Policy awareness and adherence to local fertilizer ordinances". Science of the Total Environment. 493: 898–909. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2014.06.083. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- Özhan, Koray; Bargu, Sibel (10 June 2014). "Responses of sympatric Karenia brevis, Prorocentrum minimum, and Heterosigma akashiwo to the exposure of crude oil". Ecotoxicology (2014). 23 (8): 1387–1398. doi:10.1007/s10646-014-1281-z.

- Naar, Jerome; Bourdelais, Andrea; Tomas, Carmelo (February 2002). "A Competitive ELISA to Detect Brevetoxins from Karenia brevis (Formerly Gymnodinium breve) in Seawater, Shellfish, and Mammalian Body Fluid". Environmental Health Perspectives. 110 (2): 179–185. doi:10.1289/ehp.02110179.

- Meyer, Kevin A.; O' Neil, Judith M.; Hitchcock, Gary L.; Heil, Cynthia A. (September 2014). "Microbial production along the West Florida Shelf: Responses of bacteria and viruses to the presence and phase of Karenia brevis blooms". Harmful Algae. 38 (Sp. Iss.): 110–8. doi:10.1016/j.hal.2014.04.015.