Julian's Persian War

| Julian's Persian War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Roman–Persian Wars | |||||||||

Investiture of King Shapur II by the gods Mithras (left) and Ahuramazda (right); the body of Julian is trampled underfoot. Reliefs at Taq-i Bustan. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Roman Empire Arsacid Armenia | Sassanian Empire | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Julian the Apostate Arsaces II Hormizd Procopius and Sebastianus Lucillianus | Shapur II | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

120,000 | Unknown, but presumed to be numerically inferior to the Romans[10] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| Heavy |

Moderate[11] (by modern estimations) | ||||||||

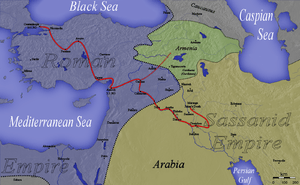

Julian's Persian War, or the Perso-Roman War of 363, was the last undertaking of the Roman emperor Julian, begun in March 363. It was an aggressive war against the Persian Empire ruled by the Sassanian king Shapur II. Shapur is believed to have expected an invasion by way of the Tigris valley. Julian sent a detachment to join with his ally Arshak II of Armenia and take the Tigris route. Meanwhile, with his main army he advanced rapidly down the Euphrates valley, meeting only scattered opposition, and reached the walls of the Persian capital Ctesiphon, where he met and defeated the Persian army at the Battle of Ctesiphon (363). Unable to take the city, and with a faltering campaign, Julian was misled by Persian spies into burning his fleet and taking a disadvantageous route of retreat in which his army was constantly harassed and his progress crawled to a halt.

In one of the skirmishes Julian was wounded and later died of his wounds, leaving his successor, Jovian, along with his army, trapped in Persian territory. The new emperor, in light of the "crushing military defeat" the Romans had suffered, was left no option but to agree to humiliating terms in order to save the remnants of his army, and himself, from complete annihilation.[12] The ignominious treaty of 363 transferred to Persian rule the major cities and fortresses of Nisibis and Singara, and renounced the alliance with Armenia, giving Shapur de facto authority to invade and annex Arsacid Armenia as a result. Thus Arsaces II of Armenia was left without any military or diplomatic support. He was captured and imprisoned by Shapur in 368; he committed suicide in 369 or 370 whilst in Persian captivity.

Aims and preparations

According to contemporary Roman sources Julian's aim was to punish the Persians for their recent invasion of Rome's eastern provinces; for this reason he refused Shapur's immediate offer of negotiations.[13] Among the leaders of the expedition was Hormizd, a brother of Shapur II, who had fled from the Persian Empire forty years earlier and had been welcomed by the then Roman emperor Constantine I. Julian is said to have intended to place Hormizd on the Persian throne in place of Shapur.[14] A devout believer in the old Roman religion, Julian asked several major oracles about the outcome of his expedition.[15]

The philosopher Sallustius, a friend of Julian, wrote advising him to abandon his plan,[16] and numerous adverse omens were reported; at the urging of other advisers he went ahead.[17] He instructed Arshak II of Armenia to prepare a large army, but without revealing its purpose;[18] he sent Lucillianus to Samosata in the upper Euphrates valley to build a fleet of river ships.[19] These preparations are thought by scholars to have suggested to Shapur that an invasion from the north, by way of the Tigris valley, was Julian's plan.

Advance

Julian had wintered at Antioch in Roman Syria. On 5 March 363 he set out north-east with his army by way of Aleppo[20] and Manbij, where fifty soldiers were killed in the collapse of a portico while they were marching under it.[21] The whole army mustered there, crossed the middle Euphrates and proceeded to Harran, known to the Romans as Carrhae, site of the famous battle in which the Roman general Crassus was defeated and killed in 53 BC. "From there two different royal highways lead to Persia," writes the eye-witness Ammianus Marcellinus: "the one on the left through Adiabene and across the Tigris; the one on the right through Assyria and across the Euphrates."[22] Julian made use of both. He sent a detachment (numbering 30,000 according to Ammianus, but only 18,000 according to Zosimus) under Procopius and Sebastianus towards the Tigris where they were to join Arshak and his Armenian army. They were then to attack the Persians from the north.[23]

Julian himself, with the larger part of his army (which numbered 65,000 although whether that was before or after Procopius' departure is unclear) turned south towards the lower Euphrates, reaching Callinicum (al-Raqqah) on 27 March and meeting the fleet under the command of Lucillianus.[24] There he was met by leaders of the "Saraceni" (Arab nomads), who offered Julian a gold crown. He refused to pay the traditional tribute in return.[25] The army followed the Euphrates downstream to Circesium (the border city) and crossed the river Aboras (Khabur) with the help of a pontoon bridge assembled for the purpose.

Progress of the war

From Circesium to Ctesiphon

Once over the border, Julian invigorated the soldiers' ardor with a fiery oration, representing his hopes and reasons for the war, and distributed a donative of 130 pieces of silver to each[26]. The army was divided on the march into three principal divisions. The center under Victor, composed of the heavy infantry; the cavalry under Arinthaeus and Hormizd the renegade Persian on the left; the right, marching along the riverbank and maintaining contact with the fleet, consisting likewise of infantry, and commanded by Nevitta. The baggage and the rearguard were under Dagalaiphus, while the scouts were led by Lucilianus, the veteran of Nisibis.[27] A by-no-means-negligible detachment was left to hold the fortress of Circesium, as several of the fickle Arabian tribes near the border were allied with Persia.

Julian then penetrated rapidly into Assyria. Since the main part of the population of Assyria was located in the towns on the banks of the Euphrates (similarly to the concentration of Egypt's population on the Nile), while the interior of the country was for the most part a desert wasteland, Julian's march, burning every town which hindered his advance and devastating the adjacent country, seriously damaged the industry of the province. Since Shapur II had not expected Julian's attack so soon, nor from that direction, Julian was practically unopposed; some Saracen cavalry harried his flanks, and the strength of the walls of Thilutha enabled it to defy the summons to surrender.[28] But the main cities of the province were captured: Anah capitulated, Macepracta fell, and the last resort of the natives, the flooding of the marshes by means of the numerous canals which criss-crossed the country for the facilitation of agriculture and trade, proved ineffectual after a momentary surprise. The diligence of the legions, who were accustomed to the versatility of Julian's commands, and the skill of the army engineers, soon repaired the ruined canals, while the barricaded roads were cleared.[29]

After Macepracta, which was reached by a march of two weeks, the army proceeded to besiege Pirisabora, the largest city of Mesopotamia, excepting Ctesiphon, the capital. Three days sufficed to conquer the city, and the capture of Pirisabora was followed by an inhuman sack. His siege engines having reduced the inner citadel, Julian left the spoils to his army, reserving only a small supply for future exigencies. The remainder of the town's wealth, including most of the population, was devoted to merciless destruction.[30] Arriving within a dozen miles of Ctesiphon, Julian put to siege the fortress of Maiozamalcha, whose formidable defenses guarded the approaches to the capital. This citadel as well was captured and destroyed, by means of a mine extended under the walls, and Julian again proved his courage in the foremost ranks of the assault. An attempt at his assassination, as he stood on a reconnaissance at some distance from the city, was foiled by Julian's own sword, which he imbrued with the blood of his assailants.[31]

Ctesiphon

After destroying the private residence, palaces and gardens of the Persian monarchy north of the capital (including an extensive managerie), and securing his position by improvised fortifications, Julian turned his attention to the city itself. The twin cities of Ctesiphon and Carche (formerly Seleucia), called Al Modain, lay before Julian to the south. In order to invest the place on both sides, Julian first dug a canal between the Euphrates and Tigris, allowing his fleet to enter the latter river, and by this means ferried his army to the further bank. A large Persian army had assembled in Ctesiphon, which was the appointed place of rendezvous for Shapur's army at the outset of the campaign; this was arrayed along the eastern bank in strong defensive positions, and it required the advantages of night-time and surprise, and subsequently a prolonged struggle on the escarpment, reportedly lasting twelve hours, to gain the passage of the river. But in the contest victory lay ultimately with the Romans, and the Persians were driven back within the city walls after sustaining losses of twenty-five hundred men; Julian's casualties are given at no more than 70.[32]

Though Julian had brought with him through Assyria a large train of siege engines and offensive weapons, and he was supplied by an active fleet which possessed the undisputed navigation of the river, the Romans appear to have been at some difficulty in putting Ctesiphon to the siege.[33] It seems difficult to ascribe Julian's rebuff to the strength of the city walls, since it had fallen on several previous occasions to conquering Roman generals. In any case Julian, confronted with his inability to capture the city, called a council of war, at which it was decided to abandon the siege. Procopius and Sebastian, perhaps naturally dilatory, were precluded by Arshak II's hostility towards Julian from executing their commission, and remained in northern Mesopotamia. Julian, considering his options before Ctesiphon, while daily challenged by its defenders to encounter Shapur in the field instead of grazing purposelessly before the adamant walls of his impregnable capital, finally gave up hope of the reinforcements necessary to capture the city. Appraised of Shapur's extensive musters in the inner provinces, and disdaining the Persian offer of a peace, he determined instead to advance into the heart of Persia to encounter the enemy in a set battle.[34]

It is possible the intention was justified by the hope of destroying the army of Shapur before the latter should join with the already numerous garrison of Ctesiphon to besiege the camp of the besiegers. More inexplicable is the burning of the fleet, and most of the provisions, which had been transported the whole course of the Euphrates with such monumental cost.[35] Although ancient and modern historians have censured the rashness of the deed, Edward Gibbon palliates the folly by observing that Julian expected a plentiful supply from the harvests of the fertile territory by which he was to march, and, with regard to the fleet, that it was not navigable up the river, and must be taken by the Persians if abandoned intact. Meanwhile, if he retreated northward with the entire army immediately, his already considerable achievements would be undone, and his prestige irreparably damaged, as one who had obtained success by stratagem and fled upon the resurgence of the foe. There were therefore no negligible reasons for his abandonment of the siege, the fleet, and the safe familiarity of the river bank.[36]

Ctesiphon to Samarra

To direct his course into the hostile inner regions of Persia, Julian procured the assistance as guides of several of his highborn captives, reportedly the same who had perfidiously implanted in his mind the conception of his present pernicious course. Their treachery inveigled him into a wandering march of several days through the deserts east of Ctesiphon, while Shapur expeditiously contrived to intercept his supply of sustenance, by firing houses, provisions, crops and farmland, wherever Julian's march approached; since the army had preserved only 20 days' provisions from the ruin of the fleet, they were soon faced with the difficulty of starvation. Shapur refused to be drawn into battle, but his cavalry perpetually harassed the outliers of the Roman camp; Julian again called a council of war, and this time he admitted the necessity of retreat.[37]

Shapur II, who had previously trembled at Julian's inexorable refusal of the offer of half the provinces of Persia and abject Sassanian dependence in exchange for peace,[38] now impetuously hurried to destroy Julian on the march. His cavalry repeatedly assailed the Romans' extended columns in the retreat; at Maranga a sharp skirmish developed into a regular battle. But the exhausted Romans were victorious, rallied personally by Julian, who shared the travails of the lowest soldier in the army. The Persian cavalry squadrons were repulsed, suffering heavy casualties; However, famine dodged the increasingly harassed Romans, as the army retired to rest in the hills south of Samarra, July 25th, 363.[39]

Samarra: Julian's death

The next day, July 26th, the advance resumed over the sloping hills and valleys in the arid wastelands south of Samarra. The heat of the day had already impelled Julian to divest himself of his helmet and protecting armor, when an alarm reached him from the rear of the column that the army was again under assault. Before the attack could be repelled, a warning from the side of the vanguard revealed that the army was surrounded in an ambush, the Persians having stolen a march to occupy the Roman route ahead. While the army struggled to form up so as to meet the manifold threats from every side, a furious charge of elephants and cavalry rattled the Roman line on the left, and Julian, to prevent its imminent collapse, led his reserves in person to shore up the defense. The light infantry under his command overthrew the massive troops of Persian heavy cavalry and elephants, and Julian, by admission of the most hostile authorities, approved his courage in the conduct of the attack. But he had plunged into the fray still unarmored, due to the desperateness of the situation, and fell stricken from a Persian dart even as the enemy fell back. The emperor toppled to the ground from off his horse, and was borne in an unconscious state from the field of battle[40]. That midnight Julian expired in his tent; “Having received from the Deity”, in his own words to the assembled officers, “in the midst of an honorable career, a splendid and glorious departure from the world.”[41]

The battle, which ended indecisively, raged until night-time. The emperor's death was offset by the heavy losses sustained by the Persians in their repulse on the main sector of the front; but in a profound sense the battle was disastrous to the Roman cause; at best, a momentary reprieve was purchased by the loss of the stay of the army of the east, and the genius of the Persian war.

Aftermath: Jovian

Defeat: Samarra to Dura

Within a few hours of Julian's death, his generals gathered under necessity of determining a successor.[42] Exigency settled on Jovian, an obscure general of the Domestic Guard, distinguished primarily for a merry heart and sociable disposition.[43] His first command subscribed the continuation of a prompt retreat. During four further days the march was directed up the river towards Corduene and the safety of the frontier, where supplies sufficient for the famished army were expected to be obtained. The Persians, revived by the intelligence of their conqueror's demise, fell twice on the rear of the retreat, and on the camp, one party penetrating to the imperial tent before being cut off and destroyed at Jovian's feet. At Dura on the fourth day the army came to a halt, deluded with the vain hope of bridging the river with makeshift contraptions of timber and animal hide. In two days, after some initial appearance of success, the futility of the endeavor was proved; but while hope of a crossing was abandoned, the march was not resumed. The spirit of the army was broken, its provisions were four days from giving out, and the verges of Corduene a hundred miles further north as yet.[44]

Peace

At this juncture, the emmisaries of Shapur II arrived in the Roman camp. According to Gibbon, Shapur was actuated by his fears of the “resistance of despair” on the part of the entrapped Roman enemy, who had come so near to toppling the Sassanian throne: conscious of the folly of refusing a peaceful but honorable settlement, obtainable at such an advantage, the Persian prudently extended the offer of a peace. Meanwhile Jovian's supplies and expedients were depleted, and in his overwhelming joy at the prospect of saving his army, his fortunes, and the empire which he lately gained, he was willing to overlook the excessive harshness of the terms, and subscribe his signature to the Imperial disgrace along with the demands of Shapur II.[45] The articles of the treaty, known to history as the treaty of Dura, stipulated the cession of Nisibis, Corduene, the four further provinces east of the Tigris which Diocletian had wrested from Persia by the Treaty of Nisibis; the Roman interest in Armenia and Iberia, as well as guaranteeing an inviolable truce of 30 years, to be warranted by mutual exchange of hostages.[46] The frontier was peeled back from the Khabur, and most of Roman Mesopotamia, along with the elaborate chain of defensive fortresses constructed by Diocletian, conceded to the enemy. The disgraced army, after succumbing to the abject necessity of its situation, was haughtily dismissed from his dominions by Shapur, and it was left to straggle across the desolate tracts of northern Mesopotamia, until at last it rejoined the army of Procopius under the walls of Thilasapha. From here the exhausted legions retired to Nisibis, where their sorry state of deprivation was finally brought to an end.[47]

Consequences

Reign of Jovian; reinstatement of Christianity

The Army had not rested long under the walls of Nisibis, when the deputies of Shapur arrived, demanding the surrender of the city in accordance with the treaty. Notwithstanding the entreaties of the populace, and those of the remainder of the territories ceded to Shapur, as also the gossip and calumnies of the Roman people, Jovian conformed to his oath; the depopulated were resettled in Amida, funds for the restoration of which were granted lavishly by the emperor.[48] From Nisibis Jovian proceeded to Antioch, where the insults of the citizenry at his cowardice soon drove the disgusted emperor to seek a more hospitable place of abode.[49] Notwithstanding widespread disaffection at the shameful accommodation which he had made, the Roman world accepted his sovereignty; the deputies of the western army met him at Tyana, on his way to Constantinople, where they rendered him homage.[50] At Dadastana, on February 17th, 364 A.D., Jovian died of unknown causes, after a reign of merely eight months.[51]

The death of Julian without naming a successor allowed the accession of the Christian Jovian, and thus destroyed Julian's ambitions of reestablishing Paganism, for the indisputably most important act of Jovian's short reign was the restoration of Christianity as the state religion. From Antioch he issued decrees immediately repealing the hostile edicts of Julian, which forbade the Christians from the teaching of secular studies, and unofficially banned them from employments in the administration of the state. The exemption of the clergy from taxes and the discharge of civil obligations was reinstated; their requirement to repair the pagan temples destroyed under Constantius II recalled; and the rebuilding of the Third Temple in Jerusalem instantly brought to a halt. At the same time, while Jovian expressed the hope that all his subjects would embrace the Christian religion, he granted the rights of conscience to all of mankind, leaving the pagans free worship in their temples (barring only certain magical rites which previously had been suppressed), and freedom from persecution to the Jews.[52]

Although very briefly under Julian Paganism appeared to be experiencing a revival, with the restoration of numerous ancient temples and ceremonies which had fallen into decay,[53] that hackneyed edifice of ancient superstition collapsed very soon upon his death, proving that it was to the base sequaciousness and avarice of his subjects, rather than to their piety, that their temporary revival of interest for the worship of the “Immortal Gods” was indebted.[54] Over the succeeding years, paganism declined further and further, and an increasing portion of the subjects of Rome, especially in the cities, passed to the profession of Christianity. Under the reign of Gratian and Theodosius, less than thirty years from the Apostate's death, the practice of pagan ceremonies was formally banned by imperial decree, and the risible relic of ancient paganism passed almost without a murmur into oblivion and illegality.

Shapur and the fate of Armenia

Armenia, abandoned to her fate, was shortly invaded and conquered by Shapur II. Arshak II of Armenia, Julian's uncooperative ally, although he maintained a valiant resistance up to four years longer, was at length abandoned by his nobles, and compelled to surrender his kingdom and person to the tender mercies of a vindictive foe. He died in ignominious captivity in Ecbatana in 371, reportedly by suicide.[55] His queen Olympias, who retreated to the fortress of Artogerassa, was able to save her son Para from the clutches of the barbaric Sassanian, before she was led to exile and death in Persia. Thereafter the Christian population of Armenia rose in revolt against the Zoroastarian Sassanids, and, with the tentative aid of Valens, who had by then ascended to the rule of the Roman east, they supported with some success the claim of Para to the throne. However, along with his title, the son had inherited the treacherous and subtle character of the father, and was discovered in a secret correspondence with Shapur. Valens was obliged to dispose by policy of a troublesome and refractory ally. After endeavoring without success to force him by persuasion from the throne, he contrived to have Para murdered at an hospitable entertainment given by a Roman count, and by an act of the blackest treachery, eternally forfeited his claim to the alliance of the people of Armenia.[56] At the date of the death of Shapur (379 A.D.) the contest remained undecided, and the accession of his brother, the moderate Ardeshir II, was the signal of peace. In 384 a formal treaty was signed between Theodosius and Shapur III, son of Shapur II, which amicably divided the kingdom of Armenia between the opposing empires, bringing the independent Armenian monarchy to an end.[57]

See also

Primary sources

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23-25

- Magnus of Carrhae FGrH 225 (fragments)

- Zosimus, Historia nova 3.12-31

- Eutropius, Breviarium 10.16

- Festus , Breviarium 28-29

- Libanius, Orations 1, 16, 17, 18, 24; Letters 737, 1367, 1402, 1508

- Ephraem Syrus, Hymns against Julian 2, 3 (Dodgeon and Lieu (1991) pp. 240-245)

- Eunapius, History after Dexippus (fragments)

- Gregory Nazianzene, Orations 5.9-15

- Socrates Scholasticus, Historia ecclesiastica 3.21-22

- Sozomen, Historia ecclesiastica 6.1-3

- Philostorgius, Historia ecclesiastica 7.15

- Theodoret of Cyrrhus, Historia ecclesiastica 3.21-26

- Passion of Artemius 69-70 (Dodgeon and Lieu (1991) pp. 238-239)

- Chronicon Pseudo-Dionysianum year 674 = 363

- John Malalas, Chronographia 13 pp. 328-337

- Zonaras, Epitome 13.13

References

- ↑ Beate Dignas & Engelbert Winter, "Rome & Persia in Late Antiquity; Neighbours & Rivals", (Cambridge University Press, English edition, 2007), p131.

- ↑ Potter, David S., "The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395", Routledge, First Edition, (Taylor & Francis Group, 2004), p520 & p527

- ↑ Potter, David S., "The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180-395", Routledge, First Edition, (Taylor & Francis Group, 2004), p520

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus,xxv.7.9-14, ed. W. Seyfarth, (Leipzig 1970-8; repr.1999)

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus,xxv.7.9-14, ed. W. Seyfarth, (Leipzig 1970-8; repr.1999)

- ↑ http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/sasanian-dynasty

- ↑ R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History, (HarperCollins, 1993), 168.

- ↑ R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History, p168.

- ↑ R. Ernest Dupuy and Trevor N. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History.

- ↑ Ghafouri, Ali. "Tarikh-e Janghay-e Iran; Az Madha ta be Emrouz", Entesharat Etela'at 1388, ISBN 964-423-738-2, p176.

- ↑ Ghafouri, Ali. "Tarikh-e Janghay-e Iran; Az Madha ta be Emrouz", The History of Persia's Wars; From the Medes to the Present", Entesharat Etela'at 1388, p176.

- ↑ Beate Dignas & Engelbert Winter, "Rome & Persia in Late Antiquity; Neighbours & Rivals", (Cambridge University Press, English edition, 2007), p94, p131 & p134

- ↑ Libanius, Orations 17.19, 18.164

- ↑ Libanius, Letters 1402.3

- ↑ Theodoret, Ecclesiastical History 3.21-25

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.5.4

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.5.10; Socrates Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History 3.21.6

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.2.2; Libanius, Orationes 18.215; Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History 6.1.2

- ↑ Magnus of Carrhae FGrH 225 F 1 (Malalas, Chronography 13 pp. 328-329)

- ↑ Dodgeon and Lieu (1991) p. 231

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.2.6

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.3.1

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.3.4-5; Zosimus, New History 3.12.3-5; Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History 6.1.2

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.3.6-9; Zosimus, New History 3.13.1-3

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae 23.3.8, 25.6.10

- ↑ Edward Gibbon, The Decline and Fall of The Roman Empire, (The Modern Library, 1932), ch. XXIV., p. 808

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 809

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 809-11

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 812, 813

- ↑ Gibbon, Ibid.

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 814

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 817-20

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 821

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 820, 821

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 822

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 822, 823

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 824

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 821

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 825, 826

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 827

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 828

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 829

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 830

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 831

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 832

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 833

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 835, 836

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 838

- ↑ Gibbon, chap. XXV., p. 844

- ↑ Gibbon, Ibid

- ↑ An Encyclopedia Of World History, (Houghton Mifflin Company Boston, 1952) chap. II., Ancient History, p. 120

- ↑ Gibbon, p.841, 842

- ↑ Gibbon, chap. XXIII., p. 769

- ↑ Gibbon, chap. XXV., p. 843

- ↑ Gibbon, p. 886

- ↑ Gibbon, pp. 887-890

- ↑ An Encyclopedia Of World History, (Houghton Mifflin Company Boston, 1952) Chap. II. Ancient History, p. 125

Bibliography

- R. Andreotti, "L'impresa di Iuliano in Oriente" in Historia vol. 4 (1930) pp. 236–273

- Timothy D. Barnes, Ammianus Marcellinus and the Representation of Historical Reality (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8014-3526-9) pp. 164–165

- Glen Warren Bowersock, Julian the Apostate (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-674-48881-4) pp. 106–119 Preview at Google Books

- J. den Boeft, J. W. Drijvers, D. den Hengst, H. C. Teitler, Philological and Historical Commentary on Ammianus Marcellinus XXIV. Leiden: Brill, 2002 Preview at Google Books

- Walter R. Chalmers, "Eunapius, Ammianus Marcellinus, and Zosimus on Julian's Persian Expedition" in Classical Quarterly n.s. vol. 10 (1960) pp. 152–160

- Franz Cumont, "La marche de l'empereur Julien d'Antioche à l'Euphrate" in F. Cumont, Etudes syriennes (Paris: Picard, 1917) pp. 1–33 Text at archive.org

- L. Dillemann, "Ammien Marcellin et les pays de l'Euphrate et du Tigre" in Syria vol. 38 (1961) p. 87 ff.

- M. H. Dodgeon, S. N. C. Lieu, The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars: 363-628 AD: a narrative sourcebook (London: Routledge, 1991) pp. 231–274 Preview (with different page numbers) at Google Books

- Ch. W. Fornara, "Julian's Persian Expedition in Ammianus and Zosimus" in Journal of Hellenic Studies vol. 111 (1991) pp. 1–15

- Edward Gibbon, The Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire, The Modern Library, 1932, New York. Chap. XXIV., XXV., pp. 798-845

- David Hunt, "Julian" in Cambridge Ancient History vol. 13 (1998. ISBN 0521302005) pp. 44–77, esp. pp. 75–76 Preview at Google Books

- W. E. Kaegi, "Constantine's and Julian's Strategies of Strategic Surprise against the Persians" in Athenaeum n.s. vol. 69 (1981) pp. 209–213

- Erich Kettenhofen, "Julian" in Encyclopaedia Iranica Online (2009-2012)

- John Matthews, The Roman Empire of Ammianus (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989. ISBN 9780801839658) pp. 140–161

- A. F. Norman, "Magnus in Ammianus, Eunapius, and Zosimus: New Evidence" in Classical Quarterly' n.s. vol. 7 (1957) pp. 129–133

- F. Paschoud, ed., Zosime: Histoire nouvelle. Vol. 2 pars 1. Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1979 (Collection Budé)

- David S. Potter, The Roman Empire at Bay: AD 180-395 (London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 9780415100571) pp. 518 et 720 Preview at Google Books

- R. T. Ridley, "Notes on Julian's Persian Expedition (363)" in Historia vol. 22 (1973) pp. 317–330 esp. p. 326

- Gerhard Wirth, "Julians Perserkrieg. Kriterien einer Katastrophe" in Richard Klein, ed., Julian Apostata (Darmstadt, 1978) p. 455 ff.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Julian's Persian War. |