Julia Robinson

| Julia Hall Bowman Robinson | |

|---|---|

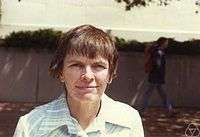

Julia Robinson in 1975 | |

| Born |

December 8, 1919 St. Louis, Missouri, United States |

| Died |

July 30, 1985 (aged 65) Oakland, California, United States |

| Nationality | United States |

| Citizenship | American |

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley |

| Known for |

Diophantine equations Decidability |

| Spouse(s) | Raphael M. Robinson |

| Awards |

Noether Lecturer (1982) MacArthur Fellow |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematician |

| Institutions | University of California, Berkeley |

| Doctoral advisor | Alfred Tarski |

| Influenced | Yuri Matiyasevich |

Julia Hall Bowman Robinson (December 8, 1919 – July 30, 1985) was an American mathematician renowned for her contributions to the fields of computability theory and computational complexity theory–most notably in decision problems. Her work on Hilbert's 10th problem played a crucial role in its ultimate resolution.

Background and education

Robinson was born in St. Louis, Missouri, the daughter of Ralph Bowers Bowman and Helen (Hall) Bowman.[1]:454 Her older sister was the mathematical popularizer and biographer Constance Reid. When the girls were a few years old, the family settled in San Diego, where Julia attended San Diego High School.[2] In 1939, she entered San Diego State University at the age of 16. In 1939, she transferred to University of California, Berkeley for her senior year and received her BA degree in 1940.[1]:454–455

After graduating, Robinson continued in graduate studies at Berkeley. As a graduate student, Robinson was employed as a teaching assistant with the Department of Mathematics and later by Jerzy Neyman in the Berkeley Statistical Laboratory, where her work resulted in her first published paper.[1]:454–455 Robinson received her Ph.D. degree in 1948 under Alfred Tarski with a dissertation on "Definability and Decision Problems in Arithmetic".[2]:52

Mathematics career

Hilbert's tenth problem

Hilbert's tenth problem asks for an algorithm to determine whether a Diophantine equation has any solutions in integers. Robinson began exploring methods for this problem in 1948 while at the RAND Corporation. Her work regarding Diophantine representation for exponentiation and her method of using Pell's equation let to the J.R. hypothesis (named after Robinson) in 1950. Proving this hypothesis would be central in the final solution. Her research publications would lead to collaborations with Martin Davis, Hilary Putnam, and Yuri Matiyasevich. In 1970, the problem was resolved in the negative; that is, they showed that no such algorithm can exist. Through the 1970's, Robinson continued working with Matiyasevich on one of their solution's corollaries, which stated that

"there is a constant N such that, given a Diophantine equation with any number of parameters and in any number of unknowns, one can effectively transform this equation into another with the same parameters but in only N unknowns such that both equations are solvable or unsolvable for the same values of the parameters."[3]

At the time the solution was first published, the authors established N = 200. Robinson and Matiyasevich's joint work would produce further reduction to 9 unknowns.[3]

George Csicsery produced and directed a one-hour documentary about Robinson titled Julia Robinson and Hilbert's Tenth Problem, that premiered at the Joint Mathematics Meeting in San Diego on January 7, 2008. Notices of the American Mathematical Society printed a film review[4] and an interview with the director.[5] College Mathematics Journal also published a film review.[6]

Other decidability work

Robinson's Ph.D. thesis, "Definability and Decision Problems in Arithmetic," showed that the theory of the rational numbers was undecidable, by demonstrating that elementary number theory could be defined in terms of the rationals. (Elementary number theory was already known to be undecidable by Gödel's first Incompleteness Theorem.)[2]:51

Other mathematical works

Robinson's work only strayed from decision problems twice.[1]:457 The first time was her first paper, published in 1948, on sequential analysis in statistics. The second was a 1951 paper in game theory where she proved that the fictitious play dynamics converges to the mixed strategy Nash equilibrium in two-player zero-sum games. This was posed by George W. Brown as a prize problem at RAND.[2]:59

Career

After obtaining her Ph.D., Robinson spent a year working at the RAND Corporation. Robinson occasionally taught for Berkeley's Department of Mathematics and was appointed full professor in 1975. [1]:472 Later on, she served as President of the American Mathematical Society from 1983-1984.[1]

Political work

In the 1950s Robinson was active in local Democratic party activities. She was Alan Cranston's campaign manager in Contra Costa County when he ran for his first political office, state controller.[2]:64–65[7]:1488

Personal life

She married Berkeley mathematics professor Raphael Robinson in 1941.[1]:455 In 1984, Robinson was diagnosed with leukemia, and she passed away in Oakland, California, on July 30, 1985.[1]:473[2]:120

Honors

- United States National Academy of Sciences elected 1976 (first woman mathematician elected[2]:vii[8]);

- Noether Lecturer 1982;[8]

- MacArthur Fellowship 1983;

- President of American Mathematical Society 1983–1984 (first woman president.[2]:vii);

- Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1985;[9]

- The Julia Robinson Mathematics Festival sponsored by the American Institute of Mathematics 2013–present and by the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute, 2007–2013, was named in her honor

Publications

- Robinson, Julia (1996). The collected works of Julia Robinson. Collected Works. 6. Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society. ISBN 978-0-8218-0575-6. MR 1411448

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Feferman, Solomon (1994). "Julia Bowman Robinson, 1919–1985" (PDF). Biographical Memoirs. 63. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences. pp. 452–479. ISBN 978-0-309-04976-4. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Reid, Constance (1996). Julia: A life in mathematics. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America. ISBN 0-88385-520-8.

- 1 2 "My Collaboration with JULIA ROBINSON". logic.pdmi.ras.ru. Retrieved 2018-08-28.

- ↑ Wood, Carol (May 2008). "Film Review: Julia Robinson and Hilbert's Tenth Problem" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. 55 (5): 573–575. ISSN 0002-9920. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ↑ Casselman, Bill (May 2008). "Interview with George Csicsery" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. 55 (5): 576–578. ISSN 0002-9920. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ↑ Murray, Margaret A. M. (September 2009). "A Film of One's Own". College Mathematics Journal. Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America. 40 (4): 306–310. ISSN 0746-8342.

- ↑ "Being Julia Robinson's Sister" (PDF). Notices of the American Mathematical Society. Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society. 43 (12): 1486–1492. December 1996. ISSN 0002-9920. Retrieved 2008-06-07.

- 1 2 "Noether Brochure: Julia Robinson, Functional Equations in Arithmetic". Association for Women in Mathematics. Retrieved 2008-06-18.

- ↑ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter R" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved July 25, 2014.

References

- Davis, Martin (1970–80). "Robinson, Julia Bowman". Dictionary of Scientific Biography. 24. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 265–268. ISBN 978-0-684-10114-9.

- Matijasevich, Yuri (1992). "My collaboration with Julia Robinson". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 14 (4): 38–45. doi:10.1007/BF03024472. ISSN 0343-6993. MR 1188142.

External links

- "Julia Bowman Robinson", Biographies of Women Mathematicians, Agnes Scott College

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Julia Robinson", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews .

- Julia Robinson at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Julia Bowman Robinson on the Internet (mirror)

- Trailer for Julia Robinson and Hilbert's Tenth Problem on YouTube