Judith Leyster

| Judith Leyster | |

|---|---|

Self-Portrait (c. 1633) | |

| Born |

c. July 28, 1609 Haarlem |

| Died |

February 10, 1660 (aged 50) Heemstede |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | The Proposition, 1631 |

Judith Jans Leyster (also Leijster) (c. July 28, 1609[1]– February 10, 1660) was a Dutch Golden Age painter. She painted genre works, portraits, and still lifes. Her entire oeuvre was attributed to Frans Hals or to her husband, Jan Miense Molenaer, until 1893 when Hofstede de Groot first attributed seven paintings to her, six of which are signed with her distinctive monogram 'JL*'.[2] Misattribution of her works to Molenaer may have been because after her death many of her paintings were inventoried as "the wife of Molenaer", not as Judith Leyster. [3]

Biography

Leyster was born in Haarlem,[4] the eighth child of Jan Willemsz Leyster, a local brewer and clothmaker. While the details of her training are uncertain, she was already well enough known in 1628 to be mentioned in a Dutch book by Samuel Ampzing titled Beschrijvinge ende lof der stadt Haerlem.

There is some speculation that Leyster pursued a career in painting as a result of her father's bankruptcy and the need to bring in funds for the family. She may have learned painting from Frans Pietersz de Grebber,[5] who was running a respected workshop in Haarlem in the 1620s.[6] During this time her family moved to the province of Utrecht, and she may have come into contact with some of the Utrecht Caravaggisti.[1]

Her first known signed work is dated 1629, four years before she entered the artists' guild.[7] By 1633 she was a member of the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. There is some debate as to who was the first woman registered with the Guild, with some sources saying it was Leyster in 1633 and others saying it was Sara van Baalbergen in 1631.[8] Dozens of other female artists may have been admitted to the Guild of St. Luke during the 17th century; however, the medium in which they worked was often not listed (at this time artists working in embroidery, pottery painting, metal and wood were included in guilds) or they were included as continuing the work of their dead husbands.[8]

Leyster's Self-Portrait, c. 1633 (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.), has been speculated to have been her presentation piece to the Guild. This work marks a historical shift from the rigidity of earlier women's self-portraits, in favor of a more relaxed, dynamic pose.[9][10] It is very relaxed by the standards of any Dutch portrait, and comparable mainly with some by Frans Hals; although it seems unlikely that in reality she wore such formal clothes when painting in oils, especially the very wide lace collar.

Within two years of her entry into the Guild, Leyster had taken on three male apprentices. Records show that Leyster sued Frans Hals for accepting a student who left her workshop for that of Hals without permission of the Guild.[11] The student's mother paid Leyster four guilders in punitive damages, only half of what Leyster asked for; and, instead of returning her apprentice, Hals settled the argument by paying a three-guilder fine. Leyster herself was fined for not having registered the apprentice with the Guild.[1]

In 1636, Leyster married Jan Miense Molenaer, a more prolific artist who worked on similar subjects. In hopes of better economic prospects, they moved to Amsterdam where he had existing clients. They remained there for eleven years before returning to the Haarlem area (in Heemstede). In Heemstede they shared a studio in a small house located in the present-day Groenendaal Park. Leyster and Molenaer had five children, only two of whom survived to adulthood.

Most of Leyster's dated works are from between 1629 and 1635, the period of her adulthood before she married and had children. There are few known pieces by her painted after 1635: two illustrations in a book about tulips from 1643, a portrait from 1652, and a still life from 1654 that was recently discovered in a private collection.[12] Leyster may have worked collaboratively with her husband as well.[1] She died in 1660, aged 50.

Work

She signed her works with a monogram of her initials JL with a star attached. This was a play on words; "Leister" meant "Lead star" in Dutch, and was for Dutch mariners of the time the common name for the North Star. The Leistar was the name of her father's brewery in Haarlem.[7] (Only occasionally did she sign her works with her full name.)

She specialized in portrait-like genre scenes of, typically, one to three figures, who generally exude good cheer, and are shown against a plain background. Many are children; others men with drink. Leyster was particularly innovative in her domestic genre scenes. These are quiet scenes of women at home, often with candle- or lamplight, particularly from a woman's point of view.[13] The Proposition (Mauritshuis, The Hague) is an unusual variant on these scenes, said by some to show a girl receiving unwelcome advances, instead of depicting—as is usual under such a title—a willing prostitute. However, this interpretation is not universally accepted.[14]

Much of her other work, especially in music-makers, was similar in nature to that of many of her contemporaries, such as her husband Molenaer, the brothers Frans and Dirck Hals, Jan Steen, and the Utrecht Caravaggisti Hendrick Terbrugghen and Gerrit van Honthorst; their genre paintings, generally of taverns and other scenes of entertainment, catered to the tastes and interests of a growing segment of the Dutch middle class. She painted few actual portraits, and her only known history painting is David with the head of Goliath, which does not depart from her typical style, with a single figure close to the front of the picture space.

Leyster and Frans Hals

Although well-known during her lifetime and esteemed by her contemporaries, Leyster and her work became largely forgotten after her death. Her rediscovery came in 1893, when it emerged that a painting admired for over a century as a work of Frans Hals had actually been painted by Leyster.

The confusion (or perhaps deceit) perhaps dates back to Leyster's lifetime. Sir Luke Schaud acquired a Leyster, The Jolly Companions, as a Hals in the 1600s. The work ended up with a dealer, Wertheimer of Bond Street, London, who described it as one of the finest Hals paintings.[15] Sir John Millars agreed with the Wertheimer about the authenticity and value of the painting. Wertheimer sold the painting to an English firm for £4,500. This firm, in turn, sold the painting as a Hals to Baron Schlichting in Paris.

In 1893 the Louvre found Leyster's monogram under the fabricated signature of Hals.[16] It is not clear when the false signature had been added. When the original signature was discovered, Baron Schlichting sued the English firm, who in turn attempted to rescind their own purchase and get their money back from the art dealer, Wertheimer. The case was settled in court on May 31, 1893, with the plaintiffs (the unnamed English firm) agreeing to keep the painting for £3,500 + £500 costs. During the legal proceedings, there was no consideration for the work as an object of value under its new history: "at no time did anyone throw his cap in the air and rejoice that another painter, capable of equalling Hals at his best, had been discovered".[15] Another version of The Jolly Companions had been sold in Brussels in 1890, and bore Leyster's monogram "crudely altered to an interlocking FH".[15]

In 1893 Cornelis Hofstede de Groot wrote the first article on Leyster.[17] Art historians since that period have often dismissed her as an imitator or follower of Hals, although this attitude has changed somewhat in the last few years.[18]

Apart from the lawsuit mentioned above, the nature of Leyster's professional relationship with Frans Hals is unclear; she may have been his student or else a friendly colleague. She may have been a witness at the baptism of Hals' daughter Maria in the early 1630s, since a "Judith Jansder" (meaning "daughter of Jan") was recorded as such, but there were other Judith Janses in Haarlem. Some historians have asserted that Hals or his brother Dirck may have been Leyster's teacher, owing to the close similarity between their work.[1]

Public collections

Museums holding works by Judith Leyster include the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam;[19] the Mauritshuis, The Hague; the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem; the Louvre, Paris; the National Gallery, London; and the National Gallery of Art, Washington DC.

Gallery

Kannekijker

Kannekijker

(A Youth with a Jug) (1633) Portrait of a Man

Portrait of a Man

A Game Of Cards

A Game Of Cards Young Flute Player

Young Flute Player

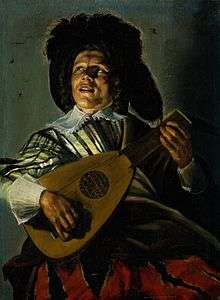

The Concert (1631–33)

The Concert (1631–33) The Proposition (1631)

The Proposition (1631) Jolly Toper (1629)

Jolly Toper (1629) Merry Trio

Merry Trio

(between 1629 and 1631) Blompotje (Flowers in a Vase) (1654)

Blompotje (Flowers in a Vase) (1654) The Jester, after Frans Hals

The Jester, after Frans Hals

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Molenaer, Judith. "Leyster, Judith, Dutch, 1609 - 1660," National Gallery of Art website. Accessed Feb. 1, 2014.

- ↑ Judith Leyster: A Woman Painter in Holland's Golden Age, by Frima Fox Hofrichter, Doornspijk, 1989, Davaco Publishers, ISBN 90-70288-62-1, p.32

- ↑ "Leyster, Judith - Oxford Reference". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195148909.001.0001/acref-9780195148909-e-603.

- ↑ Harris, Ann Sutherland and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: 1550-1950, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Knopf, New York, 1976

- ↑ Hofrichter, See Frima Fox. Judith Leyster: A Woman Painter in Holland’s Golden Age (Doornspijk, 1989), p. 14.

- ↑ "Explore Frans Pietersz. de Grebber".

- 1 2 "Explore Judith Leyster".

- 1 2 Smith, Dominic. "Who Was Judith Leyster? The Overlooked Women Artists of the Golden Age". www.theparisreview.org. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- ↑ Frances Borzello, Seeing Ourselves: Women's Self-Portraiture 1998

- ↑ Hofrichter, Frima Fox. "Judith Leyster's 'Self-Portrait': Ut Pictura Poesis," Essays in Northern European Art. Presented to Egbert Haverkamp-Bergemann on his Sixtieth Birthday, Doornspijk, 1983, pp. 106-109.

- ↑ "Leyster, Judith - Grove Art".

- ↑ "Unique painting by Judith Leyster rediscovered, to be shown in the upcoming exhibition - CODART - Dutch and Flemish art in museums worldwide". CODART. 2009-12-12. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ↑ Hofrichter, Frima Fox. "Judith Leyster's The Proposition — Between Virtue and Vice Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine.," The Feminist Art Journal vol. 4 (1975), pp. 22-26.

- ↑ See the article on the painting for a sample of the very extensive recent literature

- 1 2 3 Greer, Germaine (1979). Obstacle race : the fortunes of women painters and their work. Diane Pub Co. p. 139. ISBN 9780756791148.

- ↑ Benford, Susan. "Famous Painters: Judith Leyster". Masterpiece Cards. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ↑ Hofstede de Groot, Cornelis. "Judith Leyster," Jahrbuch der Königlich Preussischen Kunstsammlungen vol. 14 (1893), pp. 190-198; 232.

- ↑ Hofrichter, Frima Fox. "Judith Leyster: Leading Star," Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World, (Yale University, 1993).

- ↑ "Search".

- Chadwick, Whitney, Women, Art, and Society, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990.

- "Leyster, Judith" in Gaze, Delia, ed. Dictionary of Women Artists. 2 vols. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997.

- Welu, James A. and Pieter Biesboer. Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World, Yale University, 1993.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Judith Leyster. |