Juba II

| Juba II | |

|---|---|

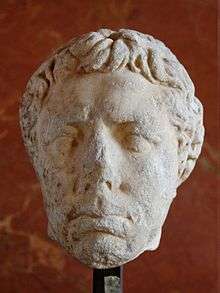

Portrait of Juba II, Louvre Museum | |

| Predecessor | Juba I |

| Successor | Ptolemy of Mauretania |

| King of Numidia | |

| Reign | 30 BC – 25 BC (5 years) |

| King of Mauretania | |

| Reign | 25 BC – AD 23 (48 years) |

| Spouse |

Princess Cleopatra Selene II Glaphyra, Princess of Cappadocia |

| Issue |

Ptolemy of Mauretania Drusilla of Mauretania |

| Father | Juba I |

Juba II (Berber: Yuba, ⵢⵓⴱⴰ; Latin: IVBA, Juba; Ancient Greek: Ἰóβας, Ἰóβα or Ἰούβας)[1] or Juba II of Mauretania (52/50 BC – AD 23) was the son of Juba I and King of Numidia and Mauretania. His first wife was Cleopatra Selene II, daughter of the Greek Ptolemaic Queen Cleopatra VII of Egypt and Roman triumvir Mark Antony.

Early life

Juba II was a Berber prince from Numidia, he was born in Hippo Regius ( Annaba in actual Algeria ). He was the only child and heir of King Juba I of Numidia; his mother's identity is unknown. In 46 BC, his father was defeated by Julius Caesar (in Thapsus, North Africa). Numidia became a Roman Province.[1] His father had been an ally of the Roman General Pompey.

Juba II was brought to Rome by Julius Caesar and he took part in Caesar’s triumphal procession. In Rome he learned Latin and Greek, became romanized and was granted Roman citizenship.[1] Through dedication to his studies, he is said to have become one of Rome's best educated citizens, and by age 20 he wrote one of his first works entitled Roman Archaeology.[1] He was raised by Julius Caesar and later by his great-nephew Octavian (future Emperor Caesar Augustus). While growing up, Juba II accompanied Octavian on military campaigns, gaining valuable experience as a leader. He fought alongside Octavian in the battle of Actium in 31 BC. They became longtime friends.

Restored to the throne

In 30 BC, Augustus restored Juba II as king of Numidia.[2][3] Juba II established Numidia as an ally of Rome. Juba II would become one of the most loyal client kings that served Rome. Probably as a result of his services to Augustus in a campaign in present-day Spain, between 26 BC and 20 BC the Emperor arranged for him to marry Cleopatra Selene II, giving her a large dowry and appointing her queen.[4] In 25 BC, Numidia became a Roman province and Juba II received Mauretania as his kingdom.[2]

Mauretania

When Juba II and Cleopatra Selene moved to Mauretania, they renamed their new capital Caesaria (modern Cherchell, Algeria), in honor of Augustus. The construction and sculpture projects at Caesaria and another city, Volubilis, display a rich mixture of Egyptian, Greek and Roman architectural styles.

Cleopatra is said to have exerted considerable influence on Juba II's policies. Juba II encouraged and supported the performing arts, research of the sciences and research of natural history. Juba II also supported Mauretanian trade. The Kingdom of Mauretania was of great importance to the Roman Empire. Mauretania traded all over the Mediterranean, particularly with Spain and Italy. Mauretania exported fish, grapes, pearls, figs, grain, wooden furniture and purple dye harvested from certain shellfish, which was used in the manufacture of purple stripes for senatorial robes. Juba II sent a contingent to Iles Purpuraires to re-establish the ancient Phoenician dye manufacturing process.[5] Tingis (modern Tangier), a town at the Pillars of Hercules (modern Strait of Gibraltar) became a major trade centre. In Gades, (modern Cádiz) and Carthago Nova (modern Cartagena) Spain, Juba II was appointed by Augustus as an honorary Duovir (a chief magistrate of a Roman colony or town), probably involving trade, and was also a Patronus Colonaie.

The value and quality of Mauretanian coins became distinguished. The Greek historian Plutarch describes him as 'one of the most gifted rulers of his time'. Between 2 BC – AD 2, he travelled with Gaius Caesar (a grandson of Augustus), as a member of his advisory staff to the troubled Eastern Mediterranean. In 21, Juba II made his son Ptolemy co-ruler and Juba II died in 23. Juba II was buried alongside his first wife in the Royal Mausoleum of Mauretania. Ptolemy then became the sole ruler of Mauretania.

Marriages and children

- First marriage to Greek Ptolemaic princess Cleopatra Selene II (40 BC – 6 AD). Their children were:

- Ptolemy of Mauretania born in ca 10 BC – 5 BC[6]

- A daughter of Cleopatra and Juba, whose name has not been recorded, is mentioned in an inscription. It has been suggested that Drusilla of Mauretania was that daughter, but she may have been a granddaughter instead. Drusilla is described as a granddaughter of Antony and Cleopatra, or may have been a daughter of Ptolemy of Mauretania.[6]

- Second marriage to Glaphyra, a princess of Cappadocia, and widow of Alexander, son of Herod the Great. Alexander was executed in 7 BC for conspiracy against his father. Glaphyra married Juba II in 6 AD or 7 AD. She then fell in love with Herod Archelaus, another son of Herod the Great and Ethnarch of Judea. Glaphyra divorced Juba to marry him in 7 AD. Juba had no children with Glaphyra.

Author

Juba wrote a number of books in Greek and Latin on history, natural history, geography, grammar, painting and theatre. He compiled a comparison of Greek and Roman institutions known as Όμοιότητες (Similarities).[7] His guide to Arabia became a bestseller in Rome. Only fragments of his work survived. He collected a substantial library on a wide variety of topics, which no doubt complemented his own prolific output. Pliny the Elder refers to him as an authority 65 times in the Natural History and in Athens, a monument was built in recognition of his writings. His extant writings are published and translated in Roller: Scholarly Kings (Chicago 2004).

Natural history

Juba II was a noted patron of the arts and sciences and sponsored several expeditions and biological research. He also was a notable author, writing several scholarly and popular scientific works such as treatises on natural history.

According to Pliny the Younger, Juba II sent an expedition to the Canary Islands and Madeira.[8] Juba II had given the Canary Islands that name because he found particularly ferocious dogs (canarius – from canis – meaning of the dogs in Latin) on the island.

Juba's Greek physician Euphorbus wrote that a succulent spurge found in the High Atlas was a powerful laxative.[9] In 12 BC, Juba named this plant Euphorbia after Euphorbus, in response to Augustus dedicating a statue to Antonius Musa, Augustus's own personal physician and Euphorbus' brother.[9] Botanist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus assigned the name Euphorbia to the entire genus in the physician's honor.[10] Euphorbia was later called Euphorbia regisjubae ("King Juba's euphorbia") to honor the king's contributions to natural history and his role in bringing the genus to notice. It is now Euphorbia regis-jubae. The palm tree genus Jubaea is also named after Juba.

Flavius Philostratus recalled one of his anecdotes: "And I have read in the discourse of Juba that elephants assist one another when they are being hunted, and that they will defend one that is exhausted, and if they can remove him out of danger, they anoint his wounds with the tears of the aloe tree, standing round him like physicians."[11]

In fiction

Juba is a lead character in Michael Livingston's 2015 historical fantasy novel The Shards of Heaven.[12][13]

A main character in Cleopatra's Daughter by Michelle Moran

A key character in "Cleopatra's Moon" A main character in "Cleopatra's Daughter" by Andrea Ashton

References

- 1 2 3 4 Roller, Duane W. (2003) The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene "Routledge (UK)". p. 1–3. ISBN 0-415-30596-9.

- 1 2 Pomponius Mela; Frank E. Romer (1998). Pomponius Mela's Description of the World. University of Michigan Press. p. 43. ISBN 0-472-08452-6.

- ↑ Michael Gagarin (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-19-517072-6.

- ↑ Roller, Duane W. (2003) The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene Routledge (UK) ISBN 0-415-30596-9 p. 74

- ↑ C.Michael Hogan, Mogador: Promontory Fort, The Megalithic Portal, ed Andy Burnham, November 2, 2007

- 1 2 Cleopatra Selene Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine. by Chris Bennett

- ↑ F Jacoby, Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft, 1916, s.v.

- ↑ O'Brien, Sally and Sarah Andrews. (2004) Lonely Planet Canary Islands "Lonely Planet". p. 59. ISBN 1-74059-374-X.

- 1 2 Flowering Plants of the Santa Monica Mountains, p 107, 1985, CNPS

- ↑ Linnaeus (1753): p.450

- ↑ Flavius Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana, Loeb Classical Library, Book II, Chapter XVI, translated by F.C. Conybeare

- ↑ "The Shards of Heaven by Michael Livingston". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Review: The Shards of Heaven by Michael Livingston". Kirkus Reviews. September 3, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2016.

- Tyldesley, Joyce (2008), Cleopatra: Last Queen of Egypt, Profile. p. 200.