Josephine Mutzenbacher

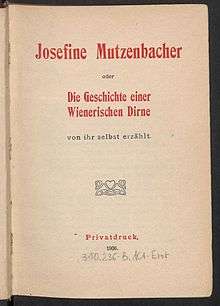

Title page from 1906. | |

| Author | Anon. (attributed to Felix Salten)[1] |

|---|---|

| Original title | Josefine Mutzenbacher oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne von ihr selbst erzählt |

| Country | Austria |

| Language | German |

| Genre | Erotica |

| Published | 1906 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 326 |

| OCLC | 757734607 |

Josephine Mutzenbacher or The Story of a Viennese Whore, as Told by Herself (German: Josefine Mutzenbacher oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne von ihr selbst erzählt) is an erotic novel first published anonymously in Vienna, Austria in 1906. The novel is famous[2][3][4] in the German-speaking world, having been in print in both German and English for over 100 years and sold over 3 million copies,[5] becoming an erotic bestseller.[6]

Although no author claimed responsibility for the work, it was originally attributed to either Felix Salten (see Bambi) or Arthur Schnitzler by the librarians at the University of Vienna.[7] Today, critics, scholars, academics and the Austrian Government designate Salten as the sole author of the "pornographic classic", Josephine Mutzenbacher.[8][9][10] The original novel uses the specific local dialect of Vienna of that time in dialogues and is therefore used as a rare source of this dialect for linguists. It also describes, to some extent, the social and economic conditions of the lower class of that time. The novel has been translated into English, French, Portuguese, Spanish, Italian, Hungarian, Hebrew, Dutch, Japanese, Swedish and Finnish,[11] and been the subject of numerous films, theater productions, parodies, and university courses, as well as two sequels.

Plot

The publisher’s preface – formatted as an orbituary and excluded from all English translations – tells that Josefine left the manuscript to her physician before her death from complications after a surgery. Josefine Mutzenbacher wasn’t her real name. The protagonist is told to been born on 20 February 1852 in Vienna and have passed on 17 December 1904 at a sanatorium.[12]

The plot device employed in Josephine Mutzenbacher is that of first-person narrative, structured in the format of a memoir. The story is told from the point of view of an accomplished aging 50-year-old Viennese courtesan who is looking back upon the sexual escapades she enjoyed during her unbridled youth in Vienna. Contrary to the title, almost the entirety of the book takes place when Josephine is between the ages of 5–12 years old, before she actually becomes a licensed prostitute in the brothels of Vienna. The book begins when she is five years old and ends when she is twelve years old and about to enter professional service in a brothel.

Although the book makes use of many "euphemisms" for human anatomy and sexual behavior that seem quaint today, its content is entirely pornographic. The actual progression of events amounts to little more than a graphic, unapologetic description of the reckless sexuality exhibited by the heroine, all before reaching her 13th year. The style bears more than a passing resemblance to the Marquis de Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom in its unabashed "laundry list" cataloging of all manner of taboo sexual antics from incest and rape to child prostitution, group sex and fellatio.

The Mutzenbacher Decision

The Mutzenbacher Decision (Case BVerfGE 83,130) was a ruling of the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany on 27 November 1990 concerning whether or not the novel Josephine Mutzenbacher should be placed on a list of youth-restricted media. However, the significance of the case came to eclipse Josephine Mutzenbacher as an individual work, because it set a precedent as to which has a larger weight in German Law: Freedom of Expression or The Protection of Youth.

Abstract

"Pornography and Art are not Mutually Exclusive."

Preface

In Germany there is a process known as Indizierung (indexing). The "Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien" (BPjM) ("Federal testing department for media harmful to youths") collates books, movies, video games and music that could be harmful to young people because they contain violence, pornography, Nazism, hate speech or similar dangerous content. The items are placed on the "Liste jugendgefährdender Medien" ("list of youth-endangering media"). Items that are "indexed" (placed on the list) cannot be bought by anyone under 18.

When an item is placed on the list, it is not allowed to be sold at regular bookstores or retailers that young people have access to, nor is it allowed to be advertised in any manner. An item that is placed on the list becomes very difficult for adults to access as a result of these restrictions. The issue underlying the Mutzenbacher Decision is not whether the book is legal for adults to buy, own, read, and sell – that is not disputed. The case concerns whether the intrinsic merit of the book as a work of art supersedes the potential harm its controversial contents could have on the impressionable minds of minors and whether or not it should be "indexed".

The history

In the 1960s, two separate publishing houses made reprints of the original 1906 Josephine Mutzenbacher. In 1965 Dehli Publishers of Copenhagen, Denmark published a two volume edition, and in 1969 the German publisher Rogner and Bernhard printed another edition. The "Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien" (BPjM) ("Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons") placed Josephine Mutzenbacher on its "Liste jugendgefährdender Medien" ("list of youth-endangering media"), commonly called "the index", after two criminal courts declared the pornographic contents of book obscene. The BPJM maintained that the book was pornographic and dangerous to minors because it contained explicit descriptions of sexual promiscuity, child prostitution, and incest as its exclusive subject matter, and promoted these activities as positive, insignificant, and even humorous behaviors in a manner devoid of any artistic value. The BPjM stated that the contents of the book justified it being placed on the "list of youth-endangering media" so that its availability to minors would be restricted. In 1978 a third publishing house attempted to issue a new version of Josephine Mutzenbacher that included a foreword and omitted the "glossary of Viennese Prostitution Terms" from the original 1906 version. The BPjM again placed Josephine Mutzenbacher on its "list of youth-endangering media" and the Rowohlt Publishing house filed an appeal with The Bundesverfassungsgericht (Federal Constitutional Court of Germany) on the grounds that Josephine Mutzenbacher was a work of art that minors should not be restricted from reading.

The decision

On 27 November 1990 The Bundesverfassungsgericht (Federal Constitutional Court of Germany) made what is now known as "The Mutzenbacher Decision". The Court prefaced their verdict by referring to two other seminal freedom of expression cases from previous German Case Law, the Mephisto Decision and the Anachronistischer Zug Decision. The court ruled that under the German Grundgesetz (constitution) chapter about Kunstfreiheit (Freedom of art) the novel Josephine Mutzenbacher was both pornography and art, and that the former is not necessary and sufficient to deny the latter. In plain English, even though the contents of Josephine Mutzenbacher are pornographic, they are still considered art and in the process of "indexing" the book, the aspect of freedom of art has to be considered. The court's ruling forced the BPjM to temporarily remove the Rowohlt edition of Josephine Mutzenbacher from its "list of youth-endangering media". This edition was added to the list again in 1992 in a new decision of the BPjM which considered the aspect of freedom of art, but deemed the aspect of protecting children to be more important. Later editions of the book by other publishers were not added to the list.

Further reading

- English Language Translation of the German Case Law[13]

- Mutzenbacher-Entscheidung des Bundesverfassungsgerichts (BVerfGE 83, 130) – German Language ruling – The Mutzenbacher Decision

- The Mutzenbacher Decision on Wikipedia Germany

- Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons General Policy Page in English

- Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons Official Statement Concerning the Mutzenbacher Decision (German)

- Federal Department for Media Harmful to Young Persons on Wikipedia Germany – Includes a list of the most popular restricted games, movies, comic books, and music not included on the English Wikipedia listing.

Derivative works

Literature

Continuations

Two novels, also written anonymously, which present a continuation of the original Josephine Mutzenbacher, have been written. However, they are not generally ascribed to Felix Salten.

Works influenced by Josephine Mutzenbacher

In 2000 the Austrian writer Franzobel published the novel "Scala Santa oder Josefine Wurznbachers Höhepunkt" (Scala Santa or Josefine Wurznbacher's Climax). The title's similarity to Josephine Mutzenbacher, being only two letters different, is a play on words that is not just coincidence.[14] The book's content is derivative as well, telling the story of the character "Pepi Wurznbacher" and her first sexual experience at age six.[15][16] The name "Pepi Wurznbacher" is directly taken from the pages of Josephine Mutzenbacher; "Pepi" was Josephine Mutzenbacher's nickname in the early chapters.[17][18] Franzobel has commented that he wanted his novel to be a retelling of the Josephine Mutzenbacher story set in modern day.[19][20] He simply took the characters, plot elements and setting from Josephine Mutzenbacher and reworked them into a thoroughly modernized version that occurs in the 1990s.[21] He was inspired to write the novel after being astounded at both the prevalence of child abuse stories in the German Press and having read Josephine Mutzenbacher's blatantly unapologetic depiction of the same.[22]

University/Academia

Josephine Mutzenbacher has been included in several university courses and symposium.[23]

- Pornography: Writing of Prostitutes COL 289 SP – Weissman, Hope Wesleyan University

- Der Sex-Akt in der Literatur. Zur Geschichte u. Repräsentation des Sex-Aktes im Spannungsfeld von "hoher Literatur, Trivialliteratur u. Pornographie" 641500 Study section, Comparative Literature Science – Babka, Anna Universität Innsbruck

- Sexuality, Eroticism, and Gender in Austrian Literature and Culture Annual Conference of the Modern Austrian Literature and Culture Association International Symposium University of Alberta 13–15 April 2007

- Literatur und Sexualität um 1900 SS 2001 510.273 – Rabelhofer, Bettina Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz

Film

| Year | German Title | Translation | Runtime | Country | Notes/English Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Josefine Mutzenbacher | Josephine Mutzenbacher | 89min | West Germany | Naughty Knickers (UK) |

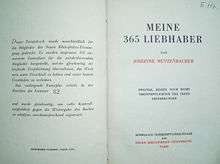

| 1971 | Josefine Mutzenbacher II – Meine 365 Liebhaber | Josephine Mutzenbacher II – My 365 Lovers | 90min | West Germany | Don't Get your Knickers in a Twist (UK) |

| 1972 | Ferdinand und die Mutzenbacherin | Ferdinand and the Mutzenbacher Girl | 81min | West Germany | The Games Schoolgirls Play (USA) |

| 1976 | Josefine Mutzenbacher- Wie sie wirklich war 1 | Josephine Mutzenbacher- The Way She Really Was | 94min | West Germany | Sensational Janine (USA) |

| 1978 | Die Beichte der Josefine Mutzenbacher | The Confession of Josephine Mutzenbacher | 94min | West Germany | Studio Tabu, Dir. Hans Billian |

| 1981 | Aus dem Tagebuch der Josefine Mutzenbacher | From the Diary of Josephine Mutzenbacher | 93min | West Germany | Professional Janine (USA) |

| 1984 | Josefine Mutzenbacher – Mein Leben für die Liebe | Josephine Mutzenbacher – My Life for Love | 100min | West Germany | The Way She Was (USA) |

| 1987 | Das Lustschloss der Josefine Mutzenbacher | The Pleasure Palace of Josephine Mutzenbacher | 85min | Germany | Insatiable Janine (USA) |

| 1990 | Josefine Mutzenbacher – Manche mögen's heiß! | Josephine Mutzenbacher – Some Like it Hot! | 90min | Germany | Studio EMS GmbH, Dir. Jürgen Enz |

| 1991 | Josefine Mutzenbacher – Die Hure von Wien | Josephine Mutzenbacher – The Whore of Vienna | 90min | Germany | Trimax Studio, Dir. Hans Billian |

| 1994 | Heidi heida! Josefine Mutzenbackers Enkelin lässt grüßen | Heidi heida! Let's Say Hello to Josephine Mutzenbacher's Granddaughter | 90min | Germany | Studio KSM GmbH |

Theater/Cabaret/Stage

The Viennese a cappella quartet 4she regularly performs a cabaret musical theatre production based on Josephine Mutzenbacher called "The 7 Songs of Josefine Mutzenbacher" ("Die 7 Lieder der Josefine Mutzenbacher"). The show is a raunchy, humorous parody of the novel, set in a brothel, that runs approximately 75 minutes.[3][24][25][26][27][28][29]

In 2002 the German actor Jürgen Tarrach and the jazz group CB-funk performed a live rendition of the texts of Josephine Mutzenbacher and Shakespeare set to modern music composed by Bernd Weißig and arranged by the Pianist Detlef Bielke of the Günther-Fischer-Quintett at the Kalkscheune in Berlin.[30][31][32]

In January 2005, Austrian actress Ulrike Beimpold gave several comedy cabaret live performances of the text of Josephine Mutzenbacher at the Auersperg15-Theater in Vienna, Austria.[33]

In an event organized by the Jazzclub Regensburg, Werner Steinmassl held a live musical reading of Josephine Mutzenbacher, accompanied by Andreas Rüsing, at the Leeren Beutel Concert Hall in Ratisbon, Bavaria, Germany called "Werner Steinmassl reads Josefine Mutzenbacher" on 3 September 2005.[34][35]

Audio adaptations

Both the original Josephine Mutzenbacher and the two "sequels" are available as spoken word audio CDs read by Austrian actress Ulrike Beimpold:

- Josefine Mutzenbacher oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne von ihr selbst erzählt. Random House Audio 2006. ISBN 3-86604-253-1.

- Josefine Mutzenbacher und ihre 365 Liebhaber. Audio CD. Götz Fritsch. Der Audio Verlag 2006. ISBN 3-89813-484-9.

In 1997 Helmut Qualtinger released "Fifi Mutzenbacher", a parody on audio CD:

- Fifi Mutzenbacher (Eine Porno-Parodie). Helmut Qualtinger (reader). Audio CD. Preiser Records (Naxos) 1997.

Exhibits

The Jewish Museum of Vienna displayed an exhibit at the Palais Eskeles called "Felix Salten: From Josephine Mutzenbacher to Bambi" where the life and work of Felix Salten was on display, which ran from December 2006 to March 2007. Austrian State Parliament Delegate Elisabeth Vitouch appeared for the opening of the exhibit at Jewish Museum Vienna and declared: "Everyone knows Bambi and Josefine Mutzenbacher even today, but the author Felix Salten is today to a large extent forgotten".[9][36][37]

Editions in English

Variety of translations

There are several English translations of Josefine Mutzenbacher, some of which, however, are pirated editions of each other.[11] All the English translations are missing the original publisher's introduction,[38] When checked against the German text, the translations differ, and the original chapter and paragraph division is not followed. For instance, the first anonymous translation from 1931 is abridged and leaves part of the sentences untranslated; on the other hand, the 1967 translation by Rudolf Schleifer contains large inauthentic expansions, as shown in the following comparison:

| 1931 edition | 1967 edition (Schleifer) | Accurate rendition of the German text |

|---|---|---|

|

My father was a very poor man who worked as a saddler in Josef City. We lived in a tenement house away out in Ottakring, at that time a new house, which was filled from top to bottom with the poorer class of tenants. All of the tenants had many children, who were forced to play in the back yards, which were much too small for so many. |

My father was a very poor journeyman saddler who worked from morning till evening in a shop in the Josefstadt, as the eighth district of Vienna is called. In order to be there at seven in the morning, he had to get up at five and leave half an hour later to catch the horse-drawn streetcar that delivered him after one and a half hour’s ride at a stop near his working place. |

My father was a penniless saddle-maker’s help who worked in a shop in Josefstadt. Our tenement building, at that time a new one, filled from top to bottom with poor folk, was far in Ottakring. All of these people had so many children that it over-crowded the small courtyards in the summer. I myself had two older brothers, both of whom were a couple of years older than I. My father, my mother, and we three children lived in a kitchen and a room, and had also one lodger. Several dozens of such lodger stayed with us for a while, one after another; they appeared and vanished, some friendly, some quarrelsome, and most of them disappeared without a trace, and we never heard from them. Among all those lodgers there were two who clearly stand out in my memory. One was a locksmith’s apprentice, a dark-haired young fellow with a sad look and always a thoroughly sooty face. We children were afraid of him. He was quiet, too, and rarely spoke much. I remember how one afternoon he came home when I was alone in our place. I was at that time five years old and was playing on the floor of the room. My mother was with the two boys in Fürstenfeld, my father not yet home from work. The apprentice picked me up, sat down and hold me on his knees. I was about to cry, but he whispered fiercely, “Lay still, I do you nothin’!”[41] |

Bibliography

- Memoirs of Josefine Mutzenbacher: The Story of a Viennese Prostitute. Translated from the German and Privately Printed. Paris [Obelisk Press?], 1931.

- Memoirs of Josefine Mutzenbacher. Illustrated by Mahlon Blaine. Paris [i.e. New York], 1931.

- The Memoirs of Josephine Mutzenbacher. Translated by Paul J. Gillette. Los Angeles, Holloway House, 1966.

- The Memoirs of Josephine Mutzenbacher: The Intimate Confessions of a Courtesan. Translated by Rudolf Schleifer [Hilary E. Holt]. Introduction by Hilary E. Holt, Ph.D. North Hollywood, Brandon House 1967.

- Memoirs of Josephine M. Complete and unexpurgated. Continental Classics Erotica Book, 113. Continental Classics, 1967.

- Oh! Oh! Josephine 1–2. London, King’s Road Publishing, 1973. ISBN 0-284-98498-1 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-284-98499-X (vol. 2)

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Josefine Mutzenbacher. |

- ↑ Eddy, Beverley Driver (2010). Felix Salten: Man of Many Faces. Riverside (Ca.): Ariadne Press. pp. 111–114. ISBN 978-1-57241-169-2.

- ↑ Outshoorn, Joyce (2004). The politics of prostitution: women's movements, democratic states, and the globalisation of sex commerce. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-521-54069-0.

Tohill, Cathal; Tombs, Pete (1995). Immoral tales: European sex & horror movies 1956–1984. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 46. ISBN 0-312-13519-X.

Lexikon. Archived 29 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

WAS IST SOLLIZITATION? Archived 30 January 2007 at the Wayback Machine. - 1 2 Wien im Rosenstolz 2006 Archived 17 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ ERBzine 0880: Mahlon Blaine Bio and Bib. Erbzine.com (5 June 1917). Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Zensur.org – Bahle: Zensur in der Literatur. Censuriana.de. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

TRANS Nr. 14: Donald G. Daviau (Riverside/California): Austria at the Turn of the Century 1900 and at the Millenium [sic] - ↑ Archived 21 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

Felix Salten, Bambi, Walt Disney – Biography – Famous People from Vienna, Austria Archived 5 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. Actilingua.com. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

Mutzenbacher, Josefine Mutzenbacher, Erotische Führung, Wienführung, Führungen in Wien, Anna Ehrlich. Wienfuehrung.com. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

Hamann, Brigitte (2000). Hitler's Vienna: a dictator's apprenticeship. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. p. 76. ISBN 0-19-514053-2. - ↑ Archived 23 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Harold B. Segel (1987). Turn-of-the-century cabaret: Paris, Barcelona, Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Cracow, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Zurich. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 183. ISBN 0-231-05128-X.

Lasky, Melvin J. (2000). The language of journalism. New Brunswick, N.J: Transaction. p. 225. ISBN 0-7658-0220-1.

Gilman, Sander L. (1985). Difference and pathology: stereotypes of sexuality, race, and madness. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. p. 44. ISBN 0-8014-9332-3.

Schnitzler, Arthur; translated by J. M. Q. Davies; with and introduction and notes by Ritchie Robertson (2004). Round dance and other plays. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. pp. X. ISBN 0-19-280459-6.

Lendvai, Paul (1998). Blacklisted: A Journalist's Life in Central Europe. I. B. Tauris. pp. XV. ISBN 1-86064-268-3.

Segel, Harold B. The Vienna Coffeehouse Wits, 1890–1938. West Lafayette, Ind: Purdue University Press. p. 166. ISBN 1-55753-033-5. - 1 2 Archivmeldung: Felix Salten: "Von Josefine Mutzenbacher bis Bambi". Wien.gv.at. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ (in German) Ungeheure Unzucht – DIE WELT – WELT ONLINE. Welt.de (3 January 2007). Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

Olympia Press Ebooks: $1 Literary and Erotic Classics From The Fabled Olympia Press Archived 28 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine.. Olympiapress.com. Retrieved on 28 November 2011. - 1 2 Felix Salten: A Preliminary Bibliography of His Works in Translation.

- ↑ Josefine Mutzenbacher oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne von ihr selbst erzählt (1906), pp. v–vi.

- ↑ UCL Laws: Institute of Global Law Archived 14 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine.. Ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Theater heute. Archived 12 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Franzobel: Scala Santa oder Josefine Wurznbachers Hoehepunkt

- ↑ (in German) Endogene Zeichen – DIE WELT – WELT ONLINE. Welt.de (1 July 2000). Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ "Die Literaturdatenbank des Österreichischen Bibliothekswerks". Biblio.at. Retrieved 2013-08-20.

- ↑ Scala Santa von Franzobel. Lyrikwelt.de. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Treibhaus Archived 29 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.. Treibhaus.at. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ http://www.wellbuilt.net/literatur/doc/franzinter.html

- ↑ (in German) Deftiges Geflügelgulasch – DIE WELT – WELT ONLINE. Welt.de (12 June 2001). Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Archived 14 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Odds & Ends, June 1998. Home.eznet.net. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ at. 4she.net. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Accessed on 9 April 2007

- ↑ Archived 13 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Events|Kurier Online Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.. Programm.kurier.at (24 January 2007). Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Mutzenbacher: Sie singt wieder Tvmedia NR. 39 23–29 September 2006 Verlagsgruppe NEWS Gesellschaft m.b.H Vienna Austria

- ↑ Ziegelwagner, Michael "Sundig Geschrammelt Und G'stanzelt" The Kurier Vienna Austria 7 October 2006

- ↑ Berliner Morgenpost: Tagestips vom 18.09.2002: Schauspieler auf neuen Wegen

- ↑ (in German) Kultur-Highlights – WELT am SONNTAG – WELT ONLINE. Welt.de (15 September 2002). Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ (in German) Jazz, Funk & Soul meets Shakespeare : Textarchiv : Berliner Zeitung. Berlinonline.de. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Beimpold las Mutzenbacher Archived 17 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Werner Steinmassl – Programme. Werner-steinmassl.de. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ Veranstaltungen – Liste. Jazzclubregensburg.de. Retrieved on 28 November 2011.

- ↑ From Josephine Mutzenbacher to Bambi. Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Felix Salten: "Von Josefine Mutzenbacher bis Bambi". ots.at. Retrieved on 28 November 2011. (in German)

- ↑ Josefine Mutzenbacher oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne von ihr selbst erzählt (1906), pp. v–vi.

- ↑ Memoirs of Josefine Mutzenbacher: The Story of a Viennese Prostitute (1931), pp. 6–7.

- ↑ The Memoirs of Josephine Mutzenbacher: The Intimate Confessions of a Courtesan (1967), pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Josefine Mutzenbacher oder Die Geschichte einer Wienerischen Dirne von ihr selbst erzählt (1906), pp. 3–4.