Jonathan Livingston Seagull (film)

| Jonathan Livingston Seagull | |

|---|---|

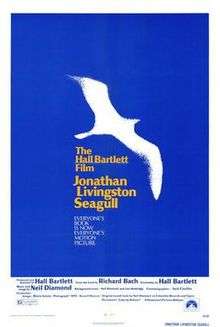

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Hall Bartlett |

| Produced by | Hall Bartlett |

| Written by |

Hall Bartlett Richard Bach (uncredited) |

| Starring |

James Franciscus Juliet Mills Hal Holbrook Dorothy McGuire Philip Ahn |

| Music by | Neil Diamond |

| Cinematography | Jack Couffer |

| Edited by |

Frank P. Keller James Galloway |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 120 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.5 million[1] |

| Box office | $1.6 million[2] |

Jonathan Livingston Seagull is a 1973 American drama film directed by Hall Bartlett, adapted from the novella of the same name by Richard Bach. The film tells the story of a young seabird who, after being cast out by his stern flock, goes on an odyssey to discover how to break the limits of his own flying speed. The film was produced by filming actual seagulls, then superimposing human dialogue over it. The film's voice actors included James Franciscus in the title role, and Philip Ahn as his mentor, Chang.

Whereas the original novella was a commercial success, the film version was poorly received by critics and barely broke even at the box office, though it was nominated for two Academy Awards: Best Cinematography and Best Editing. The soundtrack album, written and recorded by Neil Diamond, was a critical and commercial success, earning Diamond a Grammy Award and a Golden Globe Award.

Plot

As the film begins, Jonathan Livingston Seagull is soaring through the sky hoping to travel at a speed more than 60 miles per hour (100 km/h). Eventually, with luck he is able to break that barrier, but when Jonathan returns to his own flock he is greeted with anything but applause. The Elders of the flock shame Jonathan for doing things the other seagulls never dare to do. Jonathan pleads to stay and claims that he wants to share his newfound discovery with everybody, but the Elders dismiss him as an outcast, and he is banished from the flock. Jonathan goes off on his own, believing that all hope is lost. However, he is soon greeted by mysterious seagulls from other lands who assure him that his talent is a unique one, and with them Jonathan is trained to become independent and proud of his beliefs. Eventually, Jonathan himself ends up becoming a mentor for other seagulls who are suffering the same fates in their own flocks as he once did.

Production

Director Hall Bartlett first read the book Jonathan Livingston Seagull in a San Fernando Valley barbershop when he impulsively decided to call the publisher, Macmillan, and then author Richard Bach, to buy the film rights. Bartlett suggested that the story needed to be told simply, without animation or actors, and acquired the property for $100,000 and fifty percent of the profits. He granted Bach final approval rights on the film and all advertising and merchandising "gimmickry.”[3]

During production, Bartlett declared, "I was born to make this movie." [4]

Reception

The film received mainly negative reviews at the time of its release. Roger Ebert, who awarded it only one out of four stars, confessed that he had walked out of the screening after forty-five minutes, making it one of only four films he walked out on (the others being Caligula, The Statue, and Tru Loved), writing: "This has got to be the biggest pseudocultural, would-be metaphysical ripoff of the year."[5] Others used bird-related puns in their reviews, including New York Times critic Frank Rich, who called it "strictly for the birds."[6] In 1978, Jonathan Livingston Seagull was included as one of the choices in the book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time by Harry Medved with Randy Dreyfuss and Michael Medved.

In his film review column for Glamour magazine, Michael Korda considered the film "a parable couched in the form of a nature film of overpowering beauty and strength in which, perhaps to our horror, we are forced to recognize ourselves in a seagull obsessed with the heights".[7]

Awards and honors

The film was nominated for the 1973 Academy Awards for Best Cinematography (Jack Couffer) and Best Film Editing (Frank P. Keller and James Galloway).

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[8]

Lawsuits

The film was the subject of three lawsuits that were filed around the time of the film's release. Author Richard Bach sued Paramount Pictures before the film's release for having too many discrepancies between the film and the book. The judge ordered the studio to make some rewrites before it was released. Director Bartlett had allegedly violated a term in his contract with Bach which stated that no changes could be made to the film's adaptation without Bach's consent.[9] Bach's attorney claimed, "It took tremendous courage to say this motion picture had to come out of theaters unless it was changed. Paramount was stunned."[10]

Neil Diamond sued Bartlett for cutting much of his music from the film. Diamond was also upset music composer Lee Holdridge wanted to share credit with him. Bartlett was ordered to reinstate the five minutes of Diamond’s music score and three of his songs, “Anthem,” “Prologue” and “Dear Father,” and that the onscreen credits were to state “Music and songs by Neil Diamond,” “Background score composed and adapted by Neil Diamond and Lee Holdridge” and “Music supervision by Tom Catalano.”[11]

After his experience with the film, Diamond stated that he "vowed never to get involved in a movie again unless I had complete control." Bartlett angrily responded to the lawsuit by criticizing Diamond's music as having become "too slick... and it's not as much from his heart as it used to be." However, Bartlett also added, "Neil is extraordinarily talented. Often his arrogance is just a cover for the lonely and insecure person underneath."[12]

Director Ovady Julber also sued the film, claiming it stole scenes from his 1936 film La Mer. The suit was dismissed without a trial, petitioned on the grounds that extensive public school and cultural use of the film had robbed it of common-law copyright protection.[13]

Home media

Previously only available on VHS, it was released on DVD on October 23, 2007. It was released again on DVD on a manufactured-on-demand (MOD) basis through the Warner Archive Collection June 25, 2013.[14][15]

References

- ↑ "Jonathan Livingston Seagull review". Film4. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ↑ "Jonathan Livingston Seagull box office data". The Numbers. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ↑ https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/MovieDetails/54956

- ↑ "People, Oct. 22, 1973". Time. October 22, 1973.

- ↑ "Jonathan Livingston Seagull". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ↑ Movie - Film - Review, Jonathan Livingston Seagull

- ↑ Korda, Michael quote, page 544, Halliwell, Leslie Halliwells Film Guide, 6th Edition. Published by Grafton, 1987. ISBN 0-246-13207-8.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- ↑ https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1982&dat=19731011&id=zoBRAAAAIBAJ&sjid=oTMNAAAAIBAJ&pg=4871,2106784

- ↑ Campbell M. Lucas, 80; Judge Became an Entertainment Law Mediator (obituary), Elaine Woo, Los Angeles Times, May 13, 2005

- ↑ https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/MovieDetails/54956

- ↑ Having Survived a Tumor and The Jazz Singer, Neil Diamond Eases His Life Back into Shape, Carl Arrington, People, April 5, 1982

- ↑ https://catalog.afi.com/Catalog/MovieDetails/54956

- ↑ "Warner Archive Collection".

- ↑ "Amazon.com".