Jivaka Komarabhacca

| Jīvaka Komārabhacca | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Known for | Indian traditional medicine, Thai massage |

| Alma mater | Takṣaśilā |

| Other names | Kumārabhūta[1] |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | Magadhan |

| Born | Rājagṛha, Magadha |

| Died | Rājagṛha, Magadha |

| Parents |

|

| Religious career | |

| Guru | Atreya |

| Profession | Physician, healer |

| Post | Personal physician to the Buddha, King Bimbisāra, and King Ajātaśatru |

Jīvaka Komārabhacca (Sanskrit: Jīvaka Kumārabhṛta)[2] was the personal physician (Sanskrit: vaidya) of the Buddha and the Indian King Bimbisāra. He lived in Rājagṛha, present-day Rajgir, in the late 5th century BCE. Sometimes described as the "King of Medicines" (pinyin: yi wang),[2] he figures prominently in legendary accounts in Asia.

Early life

In the Chinese tradition

Texts in the Chinese tradition relate that Jīvaka is a prince in a kingdom in Central India. When the king dies, his younger brother prepares an army to battle Jīvaka. But Jīvaka says to his brother that he has not much interest in the throne, because his mind is focused on the Buddha instead. He exposes his chest, showing a Buddha image engraved on his heart. The younger brother is impressed and calls off his army. Because of this story, Jīvaka is called the 'Heart-exposing Arhat' (pinyin: Kaixin Luohan).[3]

In the Tibetan tradition

Texts in the Tibetan tradition state that Jīvaka is born as an illegitimate child of King Bimbisāra and a merchant's wife.[4][5] The king has the child raised in the court by a certain Zho-nu Jigmed, and in the court his interest in medicine is sparked when he sees some vaidyas visit. He therefore decides to train as a physician in an ancient place of learning called Takṣaśilā,[5] presently thought to be located in Islamabad, Pakistan.[4]

In the Pāli tradition

Texts from the Pāli tradition describe that Jīvaka is born in Rājagṛha as a child of a courtesan called Salāvatī, who discards him on a dust heap.[1] He is later seen by a prince called Abhaya, son of King Bimbisāra, who asks whether the child is still alive. When the people respond that it is, he decides to raise him and calls him "he who is alive" (Sanskrit and Pali: jīvaka), for having survived the ordeal.[1][4] Commentaries in the Pāli tradition explain that his second name becomes Komārabhacca, because he is raised by a prince (Pali: kumāra), but scholars have suggested the name is more likely related to the Kaumārabhṛtya: ancient Indian pediatrics.[1][3] As he grows up, Jīvaka learns about his humble origins, and determines to find himself good education to compensate for his background.[4] Without Prince Abhaya's knowledge, he goes to learn medicine at Takṣaśilā.[6][1]

Life in Takṣaśilā

He is trained for seven years in Takṣaśilā by a ṛṣi (seer) called Atreya,[1][7] which Tibetan texts say used to be the physician of Bimbisāra's father.[5] Atreya helps Jīvaka build up his observation skills.[4] During that time, Taxila was under Achaemenid rule, following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley circa 515 BCE.[8][9] The Taxila of Jivaka was probably populated by Persians, Greeks and many ethnicities coming from the various parts of the Achaemenid Empire.[10] The renowned University of Taxila enabled him to benefit from exchanges with people from various cultures.[11]

Jīvaka becomes known for his powers of observation, as depicted in many stories. In one account, Jīvaka looks at the footprint of an elephant and is able to describe the rider of the elephant in great detail, just basing himself on the elephants's footprint.[4] Tibetan texts do state that Jīvaka suffers from jealous fellow-students, however, who accuse Atreya of favoring him, because he is from the court.[5] After seven years, Jīvaka asks Atreya whether he has completed his education yet.[12] In one often cited story, Atreya then sends Jīvaka and his fellow pupils to look for any plant in the forest that does not have medicinal qualities. Jīvaka returns disappointed, however, telling Atreya that he could not find a single plant of which he did not recognize its medicinal qualities.[4][13] When Atreya is satisfied with his progress, he gives him a bit of money and sends him off.[6][1]

Life as healer

Quoted in Singh, J.; Desai, M. S.; Pandav, C. S.; Desai, S. P., 2011[4]

On his way back to Rājagṛha, Jīvaka starts his work as a physician. He heals the wife of a banker (Pali: seṭṭhī), who rewards him generously. After his return in Rājagṛha, he quickly becomes wealthy because of his service to influential patients, including King Bimbisāra.[14] Although he receives good payments from his wealthy customers, the texts state he also treats poor patients for free.[3] After curing the king of his fistula, the king appoints him as his personal physician and as a personal physician to the Buddha.[1][15]

Jīvaka is depicted healing a "misplacement" of intestines, performing an operation of trepanning on a patient,[1][16] removing an intracranial mass[16] and performing nose surgery.[17] In a more psychological case, Jīvaka treats someone with a brain condition. After having performed brain surgery, he tells the patient to lie still on the right side for seven years, on the left side for another seven years and on his back for yet another seven years. The patient lies on each side for seven days and cannot lie still for longer, standing up from his sleeping place. He confesses this to Jīvaka, who reveals to him that he ordered him seven years on each side just to persuade him to complete the full seven days on each side.[18]

In another case, King Bimbisāra lends Jīvaka to King Candappajjoti, the King of Ujjeni, to heal his condition. Candappajjoti is ill and Jīvaka knows he can only be healed by using ghee, which Candappajjoti hates. Therefore, Jīvaka gives a medicine to the king containing ghee without him being aware. Anticipating the king's response, Jīvaka flees the palace on one of the king's elephants, only to be followed closely by one of the kings's servants. When the servant catches up with Jīvaka, they eat together, Jīvaka secretly serving him a strong purgative. By the time they manage to get back to the palace, King Candappajjoti is healed and rewards Jīvaka generously.[1] An account in early Japanese literature depicts Jīvaka offering baths to the Buddha and dedicating the religious merit to all sentient beings. The story was used in Japanese society to promote the medicinal and ritual value of bathing.[19]

There are also accounts that connect Jīvaka with the miraculous. Several legends relate how Jīvaka comes in possession of miraculous wood or a miraculous gem that helps to see through the human body and discover any ailments. In these accounts, Jīvaka comes across a man or a boy carrying wooden sticks. In some accounts, the man seems to suffer terribly because of the effect of the wooden sticks, being emaciated and sweating; in other accounts, the wooden sticks which the man carries allow any by-passers to see through his back. Regardless, Jīvaka buys the sticks and finds that one of the sticks or a hidden gem is the source of the miracles, and this enables him to see through his patients' bodies and diagnose their illnesses. The accounts may have led to a myth about an ancient "ultrasound probe" as imagined in ancient Buddhist kingdoms of Asia.[20][21]

Role in Buddhism

Pāli texts often describe Jīvaka giving treatments to the Buddha for several ailments, such as when the Buddha has a cold,[22] and when he is hurt after an attempt on his life by the rebellious monk Devadatta.[3][1] The latter happened at a park called Maddakucchi, where Devadatta hurls a rock at the Buddha from a cliff. Although the rock is stopped by another rock midway, a splinter hits the Buddha's foot and causes him to bleed, but Jīvaka heals the Buddha. Jīvaka sometimes forgets to finish certain treatments, however. In such cases, the Buddha knows the healer's mind and finishes the treatment himself.[23] Jīvaka not only cares for the Buddha, but also expresses concern for the monastic community, at one point suggesting the Buddha that he has the monks exercise more often.[3]

Apart from his role as a healer, Jīvaka also develops an interest in the Buddha's teachings. One Pāli text is named after Jīvaka: the Jīvaka Sutta. In this discourse, Jīvaka inquires why the Buddha eats meat. The Buddha responds that a monk is only allowed to eat meat if the animal is not killed especially for him—apart from that, meat is allowed. He continues by saying that a monk cannot be choosy about the food he is consuming, but should receive and eat food dispassionately, just to sustain his health. The discourse makes Jīvaka glad, who decides to dedicate himself as a Buddhist lay person.[24] The Tibetan tradition has another version of Jīvaka's conversion: Jīvaka's pride that he thinks he is the best physician in the world obstructs him from accepting the Buddha. The Buddha sends Jīvaka to legendary places to find ingredients, and finally Jīvaka discovers there is still a lot he does not know yet about medicine, and it turns out that the Buddha knows a lot more. When Jīvaka accepts the Buddha as "the supreme of physicians", he is more receptive to the Buddha's teachings and the Buddha starts teaching him. Jīvaka takes upon himself the five moral precepts.[25] Pāli texts relate that Jīvaka later attains the state of śrotāpanna, a state preceding enlightenment. Having accomplished this, he starts to visit the Buddha twice a week. Since he has to travel quite far for that often, he decides to donate a mango grove close to Rājagṛha and builds a monastery there.[14][1]

At the end period of the Buddha's ministry, King Bimbisāra is killed by his son Ajātaśatru, who usurps the throne.[26] Ajātaśatru develops a tumor after he killed his father, and asks Jīvaka to heal it. Jīvaka says he needs the meat of a child to heal the tumor. As Ajātaśatru is planning to eat a child, he remembers that he killed his father. When he thinks about the killing of his father, the tumor disappears.[27] Ajātaśatru becomes ashamed of what he has done. He does not dare to see the Buddha for a while.[26] Eventually, Jīvaka manages to bring Ajātaśatru to see the Buddha to repent his misdeeds, though Ajātaśatru is suspicious and afraid at first.[3][26]

In Buddhist texts, the Buddha declares Jīvaka foremost among laypeople in being beloved by people. Jīvaka is that widely known for his healing skills, that he cannot respond to all the people that want his help. Since Jīvaka gives priority to the Buddhist monastic community, some people needing medical help seek ordination as monks to get it. Jīvaka becomes aware of this and recommends the Buddha to screen people who are ordained for certain diseases.[3]

Legacy

Jīvaka is seen by Indians as a patriarch of traditional healing,[28] and is regarded by Thai people as the creator of traditional Thai massage and medicine.[29][30] Today, Thai people still venerate him to ask for assistance in healing ailments, and many stories exist about Jīvaka's purported travels to Thailand.[30] In Chinese texts about medicine from the Six Dynasties period (early medieval), Jīvaka figures most prominently of all healers. An account about him is included in the Chinese canon of Buddhist scriptures.[2] In East Asia, several medieval medical formulas were named after him, and he is referred to in numerous medical texts. East Asian accounts about Jīvaka tend be hagiographic in nature, however, and were used more in the proselytizing of Buddhism than regarded as a medical biography.[30]

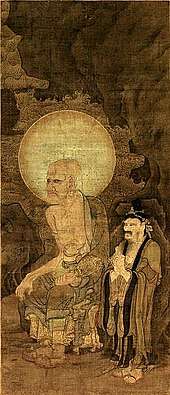

In the Sanskrit textual traditions, Jīvaka is the ninth of the Sixteen Arhats, disciples that are entrusted to protect the Buddha's teaching until the arising of the next Buddha. He is therefore believed by Buddhists to still be alive on a mountain peak called Gandhamādana, between India and Sri Lanka.[3] The monastery Jīvaka presented to the Buddhist community comes to be known as the Jīvakarāma Vihāra, Jīvakāmravaṇa or Jīvakambavana,[6][14][31] and is identified with some remains in Rajgir. The former monastery is described by archaeologists as "... one of the earliest monasteries of India dating from the Buddha's time".[32][33]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Malalasekera 1960, Jīvaka.

- 1 2 3 Salguero, C. Pierce (2009). "The Buddhist Medicine King in Literary Context: Reconsidering an Early Medieval Example of Indian Influence on Chinese Medicine and Surgery". History of Religions. 48 (3): 183. doi:10.1086/598230. JSTOR 10.1086/598230.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Buswell & Lopez 2013, Jīvaka.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Singh, J; Desai, MS; Pandav, CS; Desai, SP (2011). "Contributions of Ancient Indian Physicians: Implications for Modern Times". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 58 (1): 73–8. PMID 22387655.

- 1 2 3 4 Rabgay 2011, p. 28.

- 1 2 3 Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8.

- ↑ Deepti, R Jog; Nandakumar, Mekoth (January 2015). Educational Tourism as an Avenue of Responsible Tourism. Vision India: The Road Ahead. p. 283. ISBN 978-81-930826-0-7.

- ↑ Lowe, Roy; Yasuhara, Yoshihito (2016). The Origins of Higher Learning: Knowledge networks and the early development of universities. Routledge. p. 62. ISBN 9781317543268.

- ↑ Le, Huu Phuoc (2010). Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol. p. 50. ISBN 9780984404308.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 256. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (2010). Confession of a Buddhist Atheist. Random House Publishing Group. p. 125. ISBN 9781588369840.

- ↑ Sigambhiranyana, Phra (13 May 2011). Buddhist Scriptural Studies on the Natural Environment. 8th International Buddhist Conference on the United Nations Day of Vesak Celebrations. Thailand. p. 519.

- ↑ Manohar, Ram (January 2010). "Process of Psycho-spiritual Transformation in Traditional Ayurvedic Education and Its Contemporary Relevance". Psychology and Education: Indian Perspectives. p. 453.

- 1 2 3 Keown, Damien (2004). A Dictionary of Buddhism. Oxford University Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-19-157917-2.

- ↑ Chen, Thomas S. N.; Chen, Peter S. Y. (May 2002). "Jivaka, physician to the Buddha". Journal of Medical Biography. 10 (2): 88–91. doi:10.1177/096777200201000206. ISSN 0967-7720. PMID 11956551.

- 1 2 Banerjee, Anirban D.; Ezer, Haim; Nanda, Anil (February 2011). "Susruta and Ancient Indian Neurosurgery". World Neurosurgery. 75 (2): 320. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2010.09.007.

- ↑ Chakravarti, R.; Ray, K. (2011). "Healing and Healers Inscribed: Epigraphic Bearing on Healing-houses in Early India" (PDF). Kolkata: Institute of Development Studies.

- ↑ Braden, Charles Samuel. "Chapter 6: The Sacred Literature of Buddhism". Religion Online. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ Moerman, D. Max (2015). "The Buddha and the Bathwater: Defilement and Enlightenment in the Onsenji engi". Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 42 (1): 78. JSTOR 43551911.

- ↑ Olshin, Benjamin B. (2012). "A Revealing Reflection: The Case of the Chinese Emperor's Mirror". Icon. 18: 132–3. JSTOR 23789344.

- ↑ Chhem, Rethy K. (2013). Fangerau, H.; Chhem, R.K.; Müller, I.; Wang, S.C., eds. Medical Image: Imaging or Imagining? (PDF). Medical Imaging and Philosophy: Challenges, Reflections and Actions. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 11–2. ISBN 978-3-515-10046-5.

- ↑ Rabgay 2011, p. 30.

- ↑ Malalasekera 1960, Jīvaka, Maddakucchi.

- ↑ Buswell & Lopez 2013, Jīvakasutta.

- ↑ Rabgay 2011, p. 29–30.

- 1 2 3 Malalasekera 1960, Ajātasattu.

- ↑ Rabgay 2011, p. 29.

- ↑ "NJ legislature honors Dr Pankaj Naram". India Post. Retrieved 2017-09-06.

- ↑ Thai Massage. Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine. Thomson Gale. 2005 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- 1 2 3 Salguero, C. Pierce. "Jīvaka Across Cultures" (PDF). Thai Healing Alliance.

- ↑ "Buddhism: Buddhism In India". Encyclopedia of Religion. Thomson Gale. 2005 – via Encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Mishra, Phanikanta; Mishra, Vijayakanta (1995). Researches in Indian Archaeology, Art, Architecture, Culture and Religion: Vijayakanta Mishra Commemoration Volume. Sundeep Prakashan. p. 178. ISBN 9788185067803.

- ↑ Tadgell, Christopher (2015). The East: Buddhists, Hindus and the Sons of Heaven. Routledge. p. 498. ISBN 978-1-136-75383-1.

References

- Buswell, Robert E. Jr.; Lopez, Donald S. Jr. (2013), Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. (PDF), Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-15786-3, archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2018

- Malalasekera, G.P. (1960), Dictionary of Pāli Proper Names, Pali Text Society, OCLC 793535195

- Rabgay, Lobsang (2011), "The Origin and Growth of Medicine in Tibet", The Tibet Journal, 36 (2): 19–37

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jivaka Komarabhacca. |