James Van Ness

| James Van Ness | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| 7th Mayor of San Francisco | |

|

In office July 1, 1855 – July 7, 1856 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Palfrey Webb |

| Succeeded by | George Whelan |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1808 Burlington, Vermont |

| Died |

December 28, 1872 San Luis Obispo, California, US |

| Spouse(s) |

Caroline Frances James Lesley (m. 1836; her death 1858) |

| Parents |

Cornelius P. Van Ness Rhoda Savage |

James Van Ness (1808 – December 28, 1872) was the seventh Mayor of San Francisco, serving from 1855 to 1856.

Early life

James Van Ness was born in Burlington, Vermont, in 1808. The son of Dutch-American Cornelius P. Van Ness (1782–1852), who served as Governor of Vermont, and Rhoda Savage (d. 1834), his first wife. He was the nephew of U.S. Representative John Peter Van Ness, and William Peter Van Ness, a federal judge.

Van Ness attended Norwich University and graduated from the University of Vermont, receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree (1825) and a Master of Arts (1831). Van Ness later studied Law and became an attorney, practicing in Vermont and Georgia before relocating to California.[1]

Career

As a San Francisco alderman, he sponsored the "Van Ness Ordinance", which ordered all land within the City limits that was undeveloped at that time (that is, west of Larkin Street and southwest of Ninth Street) to be surveyed and transferred to their original deedholders.[2] Because there were many fraudulent deed holders at that time, this law led to many lawsuits for many years.[3]

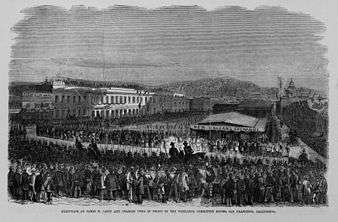

In 1855, Van Ness was elected Mayor as a Democrat. However, his administration proved ineffectual in the face of three major crises that arose. First, his election was called into question following allegations of irregularities in the outcome.[3] Then, On November 18, 1855, Charles Cora fatally shot U.S. Marshal William H. Richardson. Cora sought the safety of the sheriff at the City Jail, and Van Ness pleaded with the mob that had surrounded the jail to disperse. Another high-profile murder occurred on May 14, 1856, when James P. Casey shot newspaper editor, James King of William after King wrote an unfavorable article about Casey. After King died on May 20, the Vigilantes reformed, tried Cora and Casey, and convicted them of murder.[4]

Van Ness tried in vain to have California Governor J. Neely Johnson send State militia forces into the city to stop the executions.[5] Yet, ultimately, he watched helplessly as the Vigilantes executed Cora and Casey. Van Ness would leave office in July under the terms of the Consolidation Act (passed by the State legislature on April 29, 1856), which provided for the merger of the City and County governments into one unit. The Van Ness Ordinance was the first step in the formation of the Western Addition district.[6][7]

Van Ness would be the last mayor to be referred to as such during his term until 1862. Until then, the mayor would be known as the "President of the Board of Supervisors"

In 1860, he moved to San Luis Obispo County to practice law and, in 1871, became a State Senator.[8]

Personal life

In January 1836, Van Ness married Caroline Frances James Lesley (1808–1858). Together, they had two children:[9]

- Eliza Bird Van Ness (1838–1901), who married Frank McCoppin (1834–1897), an Irish born San Francisco mayor.

- Thomas Casey "T.C." Van Ness

Van Ness died on December 28, 1872 in San Luis Obispo, California.[10]

Honors

Van Ness Avenue is named in his honor, as well as a street in Santa Cruz, Los Angeles and Fresno.[6]

References

Notes

- ↑ The San Francisco Bay Area | The Plow, the Iron Horse, and New Towns. University of California Press. 1966. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Early San Francisco Street Names: 1846–1849 Archived January 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., San Francisco Museum.

- 1 2 Taniguchi, Nancy J. (2016). Dirty Deeds: Land, Violence, and the 1856 San Francisco Vigilance Committee. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780806157061. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Rehart, Catherine Morison (1996). The Valley's Legends & Legacies. Quill Driver Books. p. 109. ISBN 9781884995125. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Broadwater, Robert P. (2013). William T. Sherman: A Biography. ABC-CLIO. p. 39. ISBN 9781440800610. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- 1 2 Scott, Mel (1985). The San Francisco Bay Area: A Metropolis in Perspective. University of California Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780520055124. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Secrest, William B. (2004). Dark and Tangled Threads of Crime: San Francisco's Famous Police Detective Isaiah W. Lees. Quill Driver Books. p. 46. ISBN 9781884995415. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Angel, Myron (2002). History of San Luis Obispo County, California; with illustrations and biographical sketches of its prominent men and pioneers. p. 155. ISBN 9785882301261. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Journal of a Genealogist: With Ancestral Wills from Late 1500's to 1900's of More Than 50 Surnames. A.E.W. Prehn. 1980. p. 479. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ↑ Spencer, Thomas E. (1998). Where They're Buried: A Directory Containing More Than Twenty Thousand Names of Notable Persons Buried in American Cemeteries, with Listings of Many Prominent People who Were Cremated. Genealogical Publishing Com. p. 401. ISBN 9780806348230. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

Sources

- Heintz, William F., San Francisco's Mayors: 1850–1880. From the Gold Rush to the Silver Bonanza. Woodside, CA: Gilbert Roberts Publications, 1975. (Library of Congress Card No. 75-17094)