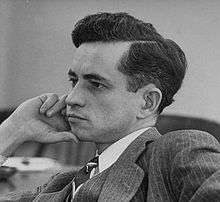

James B. Carey

| James B. Carey James B. Carey | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

James Barron Carey August 12, 1911 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

September 11, 1973 (aged 62) Silver Spring, Maryland |

| Citizenship | American |

| Employer | AFL, RATNLC, UE, CIO, IEU, AFL-CIO |

James Barron Carey (August 12, 1911 – September 11, 1973) was a 20th-century American labor union leader; secretary-treasurer of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) (1938–55); vice-president of AFL–CIO (from 1955); served as president of the United Electrical Workers (UE) (1936–41) but broke with it because of its alleged Communist control. He was the founder and president (1950–65) of the rival International Union of Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers. President Truman appointed Carey to the President's Committee on Civil Rights in 1946. Carey was labor representative to the United Nations Association (1965–72).[1] Carey helped influence the CIO’s pullout from the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) and the formation of the ICFTU dedicated to promoting free trade and democratic unionism worldwide.

Background

James Barron Carey, of Irish descent, was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on August 12, 1911, one of the eleven children of John C. Cary and Margaret Loughery. His father was a paymaster at the United States Mint in Philadelphia. Carey attended St. Theresa's Parochial School. The family moved to Glassboro, New Jersey where he graduated from Glassboro High School. At the age of fourteen he was making trellises in a local factory after school hours and during summers; while still in school he worked part-time as an apprentice projectionist in a Glassboro motion picture theater.[2] The head projectionist, who was an officer in the film operators' union, reportedly gave Carey the theory and practice of the labor movement.

Career

Union career

Carey got a job in 1929 as an electrical worker in the radio laboratory of the Philadelphia Storage Battery Company (later the Philco Corporation), and began taking evening courses in electrical engineering at Drexel Institute.[3]

Carey and six other workers at the Philco plant started the "Phil-Rod Fishing Club," primarily for the purpose of organizing a union. Discontinuing his studies at Drexel Institute, during 1931-32 Carey he attended the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School of Finance and Commerce, where he took evening courses in industrial management, business forecasting, and finance. Under the impetus of the National Industrial Recovery Act in June 1933, the radio factory set up a "Company Congress" to meet NRA collective bargaining requirements.

October 1933 Carey was sent as a delegate from his local to the convention of the American Federation of Labor (AFL). Two months later, representatives of a dozen AFL and independent unions in the radio and electrical industries met in New York, established the Radio and Allied Trades National Labor Council, and elected Carey (then 22 years old) its first president.

In 1936, when the United Electrical Workers (UE) formed, Carey served as its first President. Carey led the UE in its formative years. Under Carey’s leadership, the UE formed an affiliation with the new Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), where Carey established alliances with CIO leaders John L. Lewis (first president) and Philip Murray (second president). In 1941, he broke with the UE due to Communist control. [4]

From 1938 to 1955, Carey served as secretary-treasurer of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).

In 1948, Max Lowenthal, a Truman insider, recorded in his 1948 diary that Carey was CIO president Philip Murray's main conduit. He recorded a conversation in his diary thus:

M(ax): You know that although Jim Carey sees you, Phil Murry has been saying for three years that he has no real access to the White House.

D(avid): You should see how much Jim Carey has been in my hair these past few weeks![5]

In 1950, Carey helped found and became first president of UE rival International Union of Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers, also known as the International Union of Electrical Workers (IUE), which the CIO helped found and where he served until 1965. Today, the IUE is part of the Communications Workers of America (CWA).

In 1955, when the CIO rejoined the AFL to form the AFL-CIO, Carey became vice-president of AFL–CIO (from 1955).

Government service

In 1946, U.S. President Harry S. Truman appointed Carey to the President's Committee on Civil Rights.

From 1965 to 1972, Carey served as labor representative to the United Nations Association, where he helped influence the CIO’s pulling out from the WFTU and forming of an alternative International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) organization, dedicated to promoting free trade and democratic unionism worldwide.

Personal and death

Carey married the former Margaret McCormick in 1938. They had two children, James and Patricia.[1]

Carey died on September 11, 1973, of a heart attack at his home in Silver Spring, Maryland. He was survived by his wife and children.[1] He was interred at Gate of Heaven Cemetery in Silver Spring, Maryland.[6]

Legacy

The James B. Carey Library at Rutgers University is named for him. An exhibition documenting his career, "James B. Carey: Labor's Boy Wonder," was produced at Rutgers in 2006.[7]

More of Carey's archival records are housed at the Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs,[8] the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum[9] and the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.[10]

References

- 1 2 3 "James B. Carey Is Dead at 62". The New York Times. September 12, 1973.

- ↑ "Why Is GE Afraid of Carey?". Newspapers.com. The Berkshire Eagle. October 6, 1958. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ↑ Craft, Donna; Peck, Terrance W. (1998). Profiles of American labor unions (2nd ed.). Gale Research Inc.

- ↑ Quigel, James P. "Administrative History; the Carey Presidency in An Inventory of the Records of the President's Office of the International Union of Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers, ca. 1938-1965". Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ↑ Lowenthal, Max (1948), Dawson, Donald S., ed., 1948 Diary of Max Lowenthal, Library of Congress, p. 155

- ↑ Spencer 1998, p. 330.

- ↑ Golon, Bob. "Biography of James B. Carey". Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries. Retrieved March 19, 2016.

- ↑ James B. Carey Papers. Accession Number: LP001474. Walter P. Reuther Library of Labor and Urban Affairs.

- ↑ James B. Carey Papers. Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

- ↑ James B. Carey Oral History Interview - JFK #1, 5/26/1964. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

External sources

- Spencer, Thomas E. (1998). Where They're Buried: A Directory Containing More Than Twenty Thousand Names of Notable Persons Buried in American Cemeteries, With Listings of Many Prominent People Who Were Cremated. Baltimore, Md.: Clearfield Co. ISBN 9780806348230.

- Carey, James B. (1960). Reminiscences of James Barron Carey: oral history, 1958 (abstract). Columbia Center for Oral History. ISBN 0884550346. Retrieved March 19, 2016.