Jack and Jill (nursery rhyme)

| "Jack and Jill" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nursery rhyme | |

| Published | 1777 |

"Jack and Jill" (sometimes "Jack and Gill", particularly in earlier versions) is a traditional English nursery rhyme. The Roud Folk Song Index classifies this tune and its variations as number 10266. The rhyme dates back at least to the 18th century and exists with different numbers of verses each with a number of variations.

Text

.png)

Jack and Jill

Went up the hill

To fetch a pail of water

Jack fell down

And broke his crown,

And Jill came tumbling after.

Only a few more verses have been added to the rhyme, including a version with a total of 15 stanzas in a chapbook of the 19th century. The dab verse, probably added as part of these extensions,[1] has become a standard part of the nursery rhyme.[2] Early versions took the form:

Up Jack got,

And home did trot

As fast as he could caper;

To old Dame Dob,

Who patched his nob

With vinegar and brown paper.[1]

By the early 20th century this had been modified in some collections, such as L. E. Walter's, Mother Goose's Nursery Rhymes (London, 1919) to:

Up Jack got

And home did trot,

As fast as he could caper;

And went to bed

And plastered his head

With vinegar and brown paper.[3]

A third verse, sometimes added to the rhyme, was first recorded in a 19th-century chapbook and took

Twentieth-century versions of this verse include:

When Jill came in

How she did grin

To see Jack's paper plaster;

Mother vexed

Did whip her next

For causing Jack's disaster.[3]

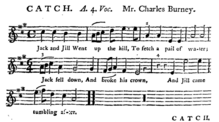

As presented above and as presented in the accompanying published images, the rhyme is made up of six-line stanzas with a rhyming scheme of aabccb and a trochaic rhythm (with the stress falling on the first of a pair of syllables). Alternatively, if these stanzas were viewed as quatrains with internal rhymes, this would be an example of ballad form, a common form for nursery rhymes.[4] The melody commonly associated with the rhyme was first recorded by the composer and nursery rhyme collector James William Elliott in his National Nursery Rhymes and Nursery Songs (1870).[5] The Roud Folk Song Index, which catalogues folk songs and their variations by number, classifies the song as 10266.[6]

History

The phrase "Jack and Jill" was in use in England as early as the 16th century to indicate a boy and a girl. A comedy with the title Jack and Jill was performed at the Elizabethan court in 1567-68, and the phrase was used twice by Shakespeare: in A Midsummer Night's Dream, which contains the line, "Jack shall have Jill; Nought shall go ill" (III:ii:460-2), and in Love's Labour's Lost, which has the lines, "Our wooing doth not end like an old play; Jack hath not Jill" (V:ii:874–5). These lines suggest that it was a phrase which indicated a romantically attached couple, as in the proverb "a good Jack makes a good Jill".[1]

The earliest known printed version comes from a reprint of John Newbery's Mother Goose's Melody, thought to have been first published in London around 1765.[7] The rhyming of "water" with "after" was taken by Iona and Peter Opie to suggest that the first verse may date from the first half of the 17th century.[1] A musical arrangement by Charles Burney was published in 1777.[8]

Meaning

Several theories have been advanced to explain its origins and to suggest meanings for the lyrics.

The game has traditionally been seen as a nonsense verse, particularly as the couple go up a hill to find water, which is often incorrectly[9] thought to be only found at the bottom of hills.[10] Vinegar and brown paper were a home cure used as a method to draw out bruises on the body.[11]

Jack is the most common name used in English-language nursery rhymes and represented an archetypal Everyman hero by the 18th century,[12] while Jill or Gill had come to mean a young girl or a sweetheart by the end of the Middle Ages.[13]

However, the woodcut that accompanied the first recorded version of the rhyme showed two boys (not a boy and a girl) and used the spelling Gill not Jill.[1]

Interpretation

The true origin of the rhyme is unknown, but there are several theories. Complicated metaphors are often said to exist within the lyrics, as is common with nursery rhyme exegesis. Most explanations post-date the first publication of the rhyme and have no corroborating evidence.[1] These include the suggestion by S. Baring-Gould in the 19th century that the rhyme is related to a narrative in the 13th-century Prose Edda section Gylfaginning composed by Icelander Snorri Sturluson. In Gylfaginning, Hjúki and Bil, brother and sister respectively in Norse mythology, were taken up from the earth by the moon (personified as the god Máni) as they were fetching water from the well called Byrgir, bearing on their shoulders the cask called Saegr and the pole called Simul.[1] Around 1835, John Bellenden Ker suggested that Jack and Jill were two priests; this was enlarged by Katherine Elwes in 1930 to indicate that Jack represented Cardinal Wolsey (c.1471–1530) and Jill was Bishop Tarbes, who negotiated the marriage of Mary Tudor to the French king in 1514.[14]

It has also been suggested that the rhyme records the attempt by King Charles I to reform the taxes on liquid measures. He was blocked by Parliament, so subsequently ordered that the volume of a Jack (1/8 pint) be reduced, but the tax remained the same. This meant that he still received more tax, despite Parliament's veto. Hence "Jack fell down and broke his crown" (many pint glasses in the UK still have a line marking the 1/2 pint level with a crown above it) "and Jill came tumbling after". The reference to "Jill" (actually a "gill", or 1/4 pint) is said to reflect that the gill dropped in volume as a consequence.[10]

The suggestion has also been made that Jack and Jill represent Louis XVI of France, who was deposed and beheaded in 1793 (lost his crown), and his Queen Marie Antoinette (who came tumbling after), a theory made difficult by the fact that the earliest printing of the rhyme pre-dates those events.[10] However, as the previous paragraph refers to King Charles I being in conflict with Parliament, the phrase "broke his crown" could also refer to that King's beheading in 1649.

There is also a local belief that the rhyme records events in the village of Kilmersdon in Somerset in 1697 when a local spinster became pregnant; the putative father is said to have died from a rock fall and the woman died in childbirth soon after.[10]

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 P. Opie and I. Opie,The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-19-869111-4, pp. 224–6.

- ↑ H. Carpenter and M. Prichard, The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), ISBN 0-19-211582-0, p. 274.

- 1 2 L. E. Walter, Mother Goose's Nursery Rhymes (1919, 1923, Forgotten Books), ISBN 1-4400-7293-0, p. 8.

- ↑ L. Turco, The Book of Forms: a Handbook of Poetics (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 3rd edn., 2000), ISBN 1-58465-022-2, pp. 28–30.

- ↑ J. J. Fuld, The Book of World-Famous Music: Classical, Popular, and Folk (Courier Dover Publications, 5th edn., 2000), ISBN 0-486-41475-2, p. 502.

- ↑ "Searchable database", English Folk Song and Dance Society, retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ↑ B. Cullinan and D. G. Person, The Continuum Encyclopedia of Children's Literature (London: Continuum, 2003), ISBN 0-8264-1778-7, p. 561.

- ↑ Arnold, John (ed.) (1777). The Essex Harmony. ii (second ed.). London: J. Buckland and S. Crowder. p. 130.

- ↑ "Groundwater". earthsci.org. Earth Science Australia. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 A. Jack, Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes (London: Penguin, 2008), ISBN 0-14-190930-7.

- ↑ C. Roberts, Heavy Words Lightly Thrown: the Reason Behind the Rhyme (Colchester: Granta, 2nd edn., 2004), ISBN 1-86207-765-7, pp. 137–40.

- ↑ W. B. McCarthy and C. Oxford, Jack in Two Worlds: Contemporary North American Tales and their Tellers (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), ISBN 0-8078-4443-8, p. xvi.

- ↑ G. A. Kleparski, "CDs, petticoats, skirts, ankas, tamaras and shielas" in C. Kay and J. J. Smith, eds, Categorization in the History of English (Amsterdam, 2004), ISBN 90-272-4775-7, p. 80.

- ↑ W. S. Baring-Gould and C. Baring Gould, The Annotated Mother Goose (Bramhall House, 1962), ISBN 0-517-02959-6, pp. 60–62.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jack and Jill. |