Ivy Mike

| Ivy Mike | |

|---|---|

The mushroom cloud from the Mike shot | |

| Information | |

| Country | United States |

| Test series | Operation Ivy |

| Test site | Enewetak |

| Date | November 1, 1952 |

| Test type | Atmospheric |

| Yield | 10.4 megatons of TNT |

| Test chronology | |

Ivy Mike was the codename given to the first test of a full-scale[1] thermonuclear device, in which part of the explosive yield comes from nuclear fusion. It was detonated on November 1, 1952 by the United States on the island of Elugelab in Enewetak Atoll, in the Pacific Ocean, as part of Operation Ivy. It was the first full test of the Teller–Ulam design, a staged fusion device.

Due to its physical size and fusion fuel type (cryogenic liquid deuterium), the Mike device was not suitable for use as a deliverable weapon; it was intended as an extremely conservative proof of concept experiment to validate the concepts used for multi-megaton detonations. A simplified and lightened bomb version (the EC-16) was prepared and scheduled to be tested in operation Castle Yankee, as a backup in case the non-cryogenic "Shrimp" fusion device (tested in Castle Bravo) failed to work; that test was cancelled when the Bravo device was tested successfully, making the cryogenic designs obsolete.

Device design and preparations

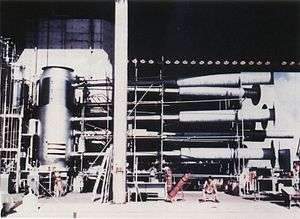

The 82-ton "Mike" device was essentially a building that resembled a factory rather than a weapon. It has been reported that Soviet engineers derisively referred to Mike as a "thermonuclear installation".[2] At its center, a very large cylindrical thermos flask or cryostat held the cryogenic deuterium fusion fuel. A regular fission bomb (the "primary") at one end was used to create the conditions needed to initiate the fusion reaction.

The device was designed by Richard Garwin, a student of Enrico Fermi, on the suggestion of Edward Teller. It had been decided that nothing other than a full-scale test would validate the idea of the Teller-Ulam design, and Garwin was instructed to use very conservative estimates when designing the test, and that it need not be small and light enough to be deployed by air.[3]

The primary stage was a TX-5 fission bomb[4]:66 (it was not boosted[4]:43) nested inside the radiation case at the upper section of the device, and it was not in contact with the "secondary" fusion stage (the TX-5 primary was also not refrigerated).[4]:43 The "secondary" fusion stage used liquid deuterium despite the difficulty of handling this material, because this fuel simplified the experiment, and made the results easier to analyze. Running down the center of the flask which held it, was a cylindrical rod of plutonium (the "sparkplug") to ignite the fusion reaction. Surrounding this assembly was a five-ton (4.5 tonne) natural uranium "tamper". The exterior of the tamper was lined with sheets of lead and polyethylene, which formed a radiation channel to conduct X-rays from the primary to secondary. The function of the X-rays was to compress the secondary; with tamper/pusher ablation, foam plasma pressure and radiation pressure. This process increases the density and temperature of the deuterium to the level needed to sustain a thermonuclear reaction, and compress the sparkplug to a supercritical mass - Inducing the sparkplug to undergo nuclear fission, to start a fusion reaction in the surrounding deuterium fuel. The outermost layer was a steel casing 10–12 inches (25–30 cm) thick. The entire assembly, nicknamed "Sausage", measured 80 inches (2.03 m) in diameter and 244 inches (6.19 m) in height and weighed about 54 tons.

The entire Mike device (including cryogenic equipment) weighed 82 short tons (73.8 metric tonnes), and was housed in a large corrugated-aluminium building called a "shot cab" which was set up on the Pacific island of Elugelab, part of the Enewetak atoll.

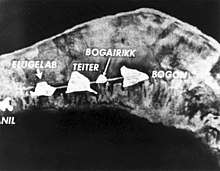

A 9,000-foot (2.7 km) artificial causeway connected the islands of Elugelab, Teiter, Bogairikk, and Bogon. Atop this causeway was an aluminium-sheathed plywood tube (named a "Krause-Ogle box") filled with helium ballonets. This allowed gamma and neutron radiation to pass uninhibited to an unmanned detection station housed in a bunker on Bogon.

In total, 9,350 military and 2,300 civilian personnel were involved in the Mike shot. A large cryogenics plant was installed on Parry Island, at the South end of the Enewetak atoll, to produce the liquid hydrogen (used for cooling the device) and deuterium needed for the test.

Detonation

The test was carried out on 1 November 1952 at 07:15 local time (19:15 on 31 October, Greenwich Mean Time). It produced a yield of 10.4 megatons of TNT.[5] However, 77% of the final yield came from fast fission of the uranium tamper, which produced large amounts of radioactive fallout.

The fireball created by the explosion had a maximum radius of 2.9 to 3.3 km (1.8 to 2.1 mi).[6][7][8] This maximum is reached a number of seconds after the detonation and during this time the hot fireball invariably rises due to buoyancy. While still relatively close to the ground, the fireball had yet to reach its maximum dimensions and was thus approximately 5.2 km (3.2 mi) wide. The mushroom cloud rose to an altitude of 17 km (56,000 ft) in less than 90 seconds. One minute later it had reached 33 km (108,000 ft), before stabilizing at 41 km (135,000 ft) with the top eventually spreading out to a diameter of 161 km (100 mi) with a stem 32 km (20 mi) wide.

The blast created a crater 1.9 km (6,230 ft) in diameter and 50 m (164 ft) deep where Elugelab had once been;[9] the blast and water waves from the explosion (some waves up to 6 m (20 ft) high) stripped the test islands clean of vegetation, as observed by a helicopter survey within 60 minutes after the test, by which time the mushroom cloud and steam were blown away. Radioactive coral debris fell upon ships positioned 56 km (35 mi) away, and the immediate area around the atoll was heavily contaminated for some time. Two new elements, einsteinium and fermium, were produced by intensely concentrated neutron flux about the detonation site.[10] One USAF pilot was lost when his F-86 Sabre crashed during a sampling mission.[11][12]

Close to the fireball, lightning discharges were rapidly triggered.[13]

The entire shot was documented by the filmmakers of Lookout Mountain studios. A post production explosion sound was overdubbed over what was a completely silent detonation from the vantage point of the camera, with the blast wave sound only arriving a number of seconds later, as akin to thunder, with the exact time depending on its distance.[14] The film was also accompanied by powerful, Wagner-esque music featured on many test films of that period and was hosted by actor Reed Hadley. A private screening was given to President Dwight D. Eisenhower who had succeeded President Harry S. Truman in January 1953.[15] In 1954, the film was released to the public after censoring, and was shown on commercial television channels.[16]

Edward Teller, perhaps the most ardent supporter of the development of the hydrogen bomb, was in Berkeley, California at the time of the shot. He was able to receive first notice that the test was successful by observing a seismometer, which picked up the shock wave that traveled through the earth from the Pacific Proving Grounds.[17] In his memoirs, Teller wrote that he immediately sent an unclassified telegram to Dr. Elizabeth "Diz" Graves, the head of the rump project remaining at Los Alamos during the shot. The unclassified telegram contained only the words "It's a boy.", which came hours earlier than any other word from Enewetak.[18][19]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The first small-scale thermonuclear test was the George explosion of Operation Greenhouse.

- ↑ Herken, Gregg: "Brotherhood Of The Bomb", notes for chapter 14 - #4. Henry Holt & Co. 2002. Notes available online at brotherhoodofthebomb.com

- ↑ Edward Teller, Memoirs: A Twentieth-Century Journey in Science and Politics (Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing, 2001), 327.

- 1 2 3 Hansen, Chuck (1995). Swords of Armageddon. III. Retrieved 2016-12-28.

- ↑ https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2014/02/27/castle-bravo-the-largest-u-s-nuclear-explosion/

- ↑ Walker, John (June 2005). "Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer". Fourmilab. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ Walker, John (June 2005). "Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer Revised Edition 1962, Based on Data from The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Revised Edition "The maximum fireball radius presented on the computer is an average between that for air and surface bursts. Thus, the fireball radius for a surface burst is 13 percent larger than that indicated and for an air burst, 13 percent smaller. "". Fourmilab. Retrieved 2009-11-22.

- ↑ "Mock up". Remm.nlm.gov. Retrieved 2013-11-30.

- ↑ Nuclear Weapon Archive

- ↑ Nuclides and Isotopes - Chart of the Nuclides, 17th Ed. Bechtel and Knolls Atomic Power Laboratory (2009)

- ↑ Pacific Wrecks memorial

- ↑ Air & Space magazine, Smithsonian Into the Mushroom Cloud Most pilots would head away from a thermonuclear explosion

- ↑ An empirical study of the nuclear explosion-induced lightning seen on IVY-MIKE

- ↑ "Nuclear Warfare Lecture 14 by Professor Grant J. Matthews of University of Notre Dame OpenCourseWare. Mechanical Shock velocity equation". Archived from the original on 2013-12-19.

- ↑ Weart, Spencer. The Rise of Nuclear Fear, p. 80 (Harvard University Press 2012).

- ↑ Weart, Spencer. Nuclear Fear: A History of Images, p. 183 (Harvard University Press, 2009).

- ↑ Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80400-X

- ↑ Teller, Memoirs, 352.

- ↑ Ford, Kenneth; Wheeler, John Archibald (2010-06-18). Geons, Black Holes, and Quantum Foam: A Life in Physics. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 227. Retrieved 2013-12-21.

References

- Chuck Hansen, U. S. Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History (Arlington: AeroFax, 1988)

- Richard Rhodes, Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Ivy. |

- The short film Operation IVY is available for free download at the Internet Archive — formerly classified.

- Nuclearweaponarchive.org: Operation Ivy

- Sonicbomb.com: "Ivy Mike test" video

- Technical Photography on Operation Ivy by EG&G — "Full Text". (5.5 MB)

Coordinates: 11°40′0″N 162°11′13″E / 11.66667°N 162.18694°E