Itinerant court

The modern capital city has, historically, not always existed. In medieval Western Europe, a migrating form of government was more common: the itinerant court or travelling kingdom. This was the only existing West European form of kingship in the Early Middle Ages, and remained so until around the middle of the thirteenth century, when permanent (stationary) royal residences began to develop - i.e. embryonic capital cities.

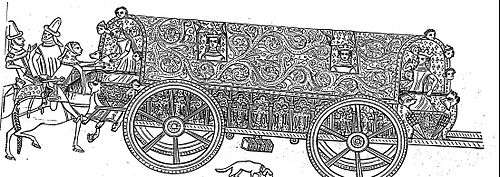

The itinerant court can be defined as the alternative to having a capital city, a permanent political centre from which a kingdom is governed. Especially medieval Western Europe was characterized by a political rule where the highest political authorities constantly changed their whereabouts, bringing with them (the whole or parts of) the country's central government on their journey. The kingdom thus had no real centre, no permanent seat of government.

German itinerant kingship

This manner of ruling a country is particularly strongly associated with German history, where the emergence of a capital city took an unusually long time. The German itinerant regime ("Reisekönigtum") was, from the Frankish period and up to late medieval times, the usual form of royal or imperial government. The Holy Roman Emperors, in the Middle Ages and even later, did not rule from any permanent central residence. They constantly traveled, with their family and court, through the kingdom.

The Holy Roman Empire did not have even a rudimentary capital city; the emperor and other princes ruled by constantly changing their residence. Imperial dwelling-places were typically palaces built by the Crown, sometimes episcopal cities. The routes followed by the court during the journeys are usually called "itineraries". Palaces were notably erected in accessible, fertile areas - surrounded by Crown mansions, where imperial rights to local resources existed. These princely estates were scattered around the whole country. The composition of the ruler's retinue changed constantly, depending on what area the court was passing through, and which noblemen joined their master on the trip, or left him again.

During the course of a year, impressive distances were passed through. German historians calculate for example, on the basis of royal letters and charters, that Emperor Henry VI and his entourage in 1193 (between January 28 and December 20) traversed more than 4,000 kilometres - crisscrossing the entire German area. A reconstruction of destinations gives the following chronological route: Regensburg – Würzburg – Speyer – Hagenau – Straßburg – Hagenau – Boppard – Mosbach – Würzburg – Gelnhausen – Koblenz – Worms – Kaiserslautern – Worms – Haßloch – Straßburg – Kaiserslautern – Würzburg – Sinzig – Aachen – Kaiserswerth – Gelnhausen – Frankfurt am Main – and finally Gelnhausen again.

The itinerant court in other countries

The itinerant court is often conceived as a typically German institution. Not only medieval Germany was, however, ruled in a migrating way. This was also the case in most other contemporary European countries, where terms like "corte itinerante" describe this phenomenon. Kings and their companions traveled continuously from one royal palace to the next. The old Parliament of Scotland assembled in many different places, Scotland being ruled by an itinerant court in early historical sources. In royal pre-conquest England, conditions were the same.[1]

A more centralized way of ruling did evolve during this time, but only slowly and gradually.[2] London and Paris began to develop into permanent political centers from the late 1300s, when Lisbon also showed similar tendencies. (Spain, on the other hand, lacked a fixed royal residence until Philip II elevated El Escorial outside Madrid to this rank.) Smaller kingdoms had a similar, but slower development.[3]

The itinerant court and the evolving capital city

Germany never developed a fixed capital city during the medieval or early modern period. "Multizentralität" remained its alternative solution: a decentralized state where the governmental functions never ended up in just one place until the late modern period.

England was very different in this respect. Central political power was permanently established in London approximately in the middle of the fourteenth century, but London's outstanding position as a financial center was firmly established many centuries earlier. A monarch like King Henry II of England (1133-1189) was evidently attracted by its great wealth, but he was hesitant about taking up residence there. During his reign, London was becoming as near to an economic capital as the conditions of the age allowed. But its very prosperity and its extensive liberties forbade it as a desirable place of residence for the king and his court, and stood in the way of its becoming a political capital. The king often wished to be near the great city, but he claimed the same power to control his own court that the citizens demanded to govern their own city. The only way to avoid conflict between the household jurisdiction and the municipal jurisdiction was for the king to keep away from the latter much of the time. He could only be in the city as a guest or a conqueror. Accordingly, he seldom ventured within the city walls. He established himself on such occasions either in the Tower fortress or at his palace of Westminster just outside London town.

London was the natural leader among English towns. In order to control England it was necessary for the kings to control London first. But London was too powerful to control, and it took centuries before the monarchs finally settled down there. They tried, unsuccessfully, to drive the London merchants out of business by making Westminster a rival economic center. They tried to find some other suitable place in the Kingdom where they could deposit their archives, which were gradually growing too large and heavy to be transported with them on their unending journeys. York tended, during a time of war with Scotland, towards becoming a political capital. But then came the Hundred Years' War against France and the political center of gravity again shifted to the southern parts of England, where London was totally dominating. Gradually, many of the institutions of the State ceased to follow the king on his journeys, and established themselves permanently in London: the Treasury, the Parliament, the court. Last of all, the king experienced a need to take up permanent residence in London himself. But it was possible for him to make London his capital city only after he had become powerful enough to "tame the financial metropolis" and transform it into an obedient tool of the State authority.[4]

The English historical example clearly shows that a political center does not naturally evolve at the same place as the economically most important place in a given country. It has a certain tendency of doing so, admittedly. But centralizing and centrifugal forces counteracted each other at this time, at the same time as wealth was both an attractive and a repelling force vis-à-vis the rulers.

The purpose of the itinerant court

A migrating form of political was a natural ingredient in the feudalism that succeeded the more centralized Roman Empire of old. In Eastern Europe, ancient Constantinople retained the characteristics of a political capital city much more than any western city. But why did the West European itinerant kingship persist for such a long time?

This travelling government enabled a better surveillance of the realm. The king's nomadic lifestyle also facilitated control over local magnates, strengthening national cohesion. Medieval government was for a long time a system of personal relationships, rather than an administration of geographic areas. Therefore, the ruler had to "personally" deal with his subordinates. This "oral" culture gradually, during medieval times, gave way to a "documentary" type of rule - based on written communication, which generated archives, making stationary rule increasingly more attractive to the kings.

Originally, rulers also needed to travel in order to meet the court's purely financial needs - because contemporary inadequate transportation facilities simply did not allow a large group of people to stay permanently in one place. (Instead of sending food to the government, the government wandered to the food, so to speak.) In many countries, however, the traveling kingship persisted throughout the 1500s or even longer - when food supplies and other necessities were, however, normally instead transferred to the place where the court resided for the moment. Consequently, these pure economic benefits must have been clearly less decisive than the political importance of traveling. The transition from a state with an itinerant court to a state ruled from a capital city was a reflection of how an "oral" way of life (when kings could win loyalty only by personally meeting their subjects face to face) gave way to a "documentary" rule (when the ruler was able to order people around simply by letting his incipient bureaucracy send them a written message).

Bibliography

- Karl Otmar von Aretin: Das Reich ohne Hauptstadt? In: Hauptstädte in europäischen Nationalstaaten. ed T Schieder & G Brunn, Munich/Vienna 1983.

- Wilhelm Berges: Das Reich ohne Hauptstadt. In: Das Hauptstadtproblem in der Geschichte Tübingen 1952.

- John W. Bernhardt: Itinerant kingship and royal monasteries in early medieval Germany, 936–1075. CUP, Cambridge 1993, ISBN 0-521-39489-9.

- Carlrichard Brühl: Fodrum, Gistum, Servitium Regis. Cologne/Graz 1968.

- Fernand Braudel: Capitalism and material life 1400-1800, Harper & Row, New York 1973.

- Edith Ennen: Funktions- und Bedeutungswandel der 'Hauptstadt' vom Mittelalter zur Moderne. In: Hauptstädte in europäischen Nationalstaaten ed. Theodor Schieder & Gerhard Brunn, Munich/Vienna 1983.

- Fernández, Luis (1981a): España en tiempo de Felipe II, Historia de España, ed R Menéndez Pidal, tomo XXII, vol I, cuarta edición, Madrid.

- Fernández, Luis (1981b): España en tiempo de Felipe II, Historia de España, ed R Menéndez Pidal, tomo XXII, vol II, cuarta edición, Madrid.

- František Graus: Prag als Mitte Böhmens. In: Zentralität als Problem der mittelalterlichen Stadtgeschichtsforschung. ed. F Meynen, Vienna/Cologne 1979.

- Bernard Guenee: States and rulers in later medieval Europe. Glasgow 1985.

- T. Duffus Hardy: A Description of the Patent Rolls, London 1835.

- Oliver Hermann: Lothar III. und sein Wirkungsbereich. Räumliche Bezüge königlichen Handelns im hochmittelalterlichen Reich (1125–1137). Winkler, Bochum 2000, ISBN 3-930083-60-4.

- Jusserand, J.J.: English wayfaring life in the Middle Ages (XIVth century), 2nd revised and enlarged edition, London 1921.

- Mina Martens: Bruxelles, capitale de fait sous les Bourgignons. In: Vierteljahrschrift für Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte. II, 1964.

- Ferdinand Opll: Das itinerar Kaiser Friedrichs Barbarossa. Vienna/Cologne/Graz 1978.

- Hans Jacob Orning: Unpredictability and presence - Norwegian Kingship in the High Middle Ages. Leiden/Boston 2008.

- Hans Conrad Peyer: Das Reisekönigtum des Mittelalters. In: Vierteljahrschrift für Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte. ed. Hermann Aubin, vol 51, Wiesbaden 1964, S. 1–21.

- Gustav Roloff: Hauptstadt und Staat in Frankreich. In: Das Hauptstadtproblem in der Geschichte. Tübingen 1952.

- Peter Sawyer: The royal tun in pre-conquest England. In: Ideal and reality in Frankish and Anglo-Saxon society, Oxford 1983.

- JBLD Strömberg: The Swedish Kings in Progress – and the Centre of Power. In: Scandia. 70:2, Lund 2004.

- JBLD Strömberg: De svenska resande kungarna – och maktens centrum. (The Swedish travelling kingdom –and the center of power) Uppsala 2013. Samlingar utgivna av Svenska fornskriftsällskapet. Serie 1. Svenska skrifter 97, 557 pp. ISBN 978-91-979881-1-7. English summary:

- Thomas Frederick Tout: The beginnings of a modern capital, London and Westminster in the fourteenth century. In: The collected papers of Thomas Frederick Tout vol III, Manchester 1934.

Footnotes

- ↑ Peter Sawyer 1983.

- ↑ A general survey in Guenee 1985, pp. 126 etc, 238 etc; Peyer 1964.

- ↑ About the German development, see von Aretin, Berges, Bernhardt, Brühl, Ennen, Hermann and Opll. About Brussels, see Martens. About French conditions, see Roloff. About Scandinavia, see Orning and Stromberg (2004, 2013). About Prague, see Graus. About Spain, see Fernández 1981a, pp. 63, 77, 599, 601, 602, 605; Fernández 1981b, pp. 609, 617, 662.

- ↑ About "taming" of autonomous cities, see Braudel 1973 p. 402-406. About English conditions, see especially Tout 1934, and Jusserand 1921 p. 83, 104, 108, 118. John Lackland's itinerary in Hardy 1835.