Irreducible representation

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

|

|

Infinite dimensional Lie group

|

In mathematics, specifically in the representation theory of groups and algebras, an irreducible representation or irrep of an algebraic structure is a nonzero representation that has no proper subrepresentation closed under the action of .

Every finite-dimensional unitary representation on a Hermitian vector space is the direct sum of irreducible representations. As irreducible representations are always indecomposable (i.e. cannot be decomposed further into a direct sum of representations), these terms are often confused; however, in general there are many reducible but indecomposable representations, such as the two-dimensional representation of the real numbers acting by upper triangular unipotent matrices.

History

Group representation theory was generalized by Richard Brauer from the 1940s to give modular representation theory, in which the matrix operators act over a field of arbitrary characteristic, rather than a vector space of real or complex numbers. The structure analogous to an irreducible representation in the resulting theory is a simple module.

Overview

Let be a representation i.e. a homomorphism of a group where is a vector space over a field . If we pick a basis for , can be thought of as a function (a homomorphism) from a group into a set of invertible matrices and in this context is called a matrix representation. However, it simplifies things greatly if we think of the space without a basis.

A linear subspace is called -invariant if for all and all . The restriction of to a -invariant subspace is known as a subrepresentation. A representation is said to be irreducible if it has only trivial subrepresentations (all representations can form a subrepresentation with the trivial -invariant subspaces, e.g. the whole vector space , and {0}). If there is a proper non-trivial invariant subspace, is said to be reducible.

Notation and terminology of group representations

Group elements can be represented by matrices, although the term "represented" has a specific and precise meaning in this context. A representation of a group is a mapping from the group elements to the general linear group of matrices. As notation, let a, b, c... denote elements of a group G with group product signified without any symbol, so ab is the group product of a and b and is also an element of G, and let representations be indicated by D. The representation of a is written

By definition of group representations, the representation of a group product is translated into matrix multiplication of the representations:

If e is the identity element of the group (so that ae = ea = a, etc.), then D(e) is an identity matrix, or identically a block matrix of identity matrices, since we must have

and similarly for all other group elements.

Decomposable and Indecomposable representations

A representation is decomposable if a similar matrix P can be found for the similarity transformation:[1]

which diagonalizes every matrix in the representation into the same pattern of diagonal blocks – each of the blocks are representation of the group independent of each other. The representations D(a) and D'(a) are said to be equivalent representations.[2] The representation can be decomposed into a direct sum of k matrices:

so D(a) is decomposable, and it is customary to label the decomposed matrices by a superscript in brackets, as in D(n)(a) for n = 1, 2, ..., k, although some authors just write the numerical label without brackets.

The dimension of D(a) is the sum of the dimensions of the blocks:

If this is not possible, then the representation is indecomposable.[1][3]

Examples of Irreducible Representations

Trivial Representation

All groups have a one-dimensional, irreducible trivial representation. More generally, any one-dimensional representation is irreducible by virtue of having no proper nontrivial subspaces.

Irreducible Complex Representations

The irreducible complex representations of a finite group G can be characterized using results from character theory. In particular, all such representations decompose as a direct sum of irreps, and the number of irreps of is equal to the number of conjugacy classes of .[4]

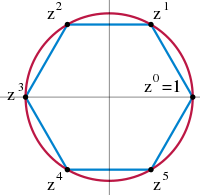

- The irreducible complex representations of are exactly given by the maps , where is an th root of unity.

- Let be an -dimensional complex representation of with basis . Then decomposes as a direct sum of the irreps and the orthogonal subspace given by:

- The former irrep is one-dimensional and isomorphic to the trivial representation of . The latter is dimensional and is known as the standard representation of .[4]

- Let be a group. The regular representation of is the free complex vector space on the basis with the group action , denoted . All irreducible representations of appear in the decomposition of as a direct sum of irreps.

Applications in theoretical physics and chemistry

In quantum physics and quantum chemistry, each set of degenerate eigenstates of the Hamiltonian operator comprises a vector space V for a representation of the symmetry group of the Hamiltonian, a "multiplet", best studied through reduction to its irreducible parts. Identifying the irreducible representations therefore allows one to label the states, predict how they will split under perturbations; or transition to other states in V. Thus, in quantum mechanics, irreducible representations of the symmetry group of the system partially or completely label the energy levels of the system, allowing the selection rules to be determined.[5]

Lie groups

Lorentz group

The irreps of D(K) and D(J), where J is the generator of rotations and K the generator of boosts, can be used to build to spin representations of the Lorentz group, because they are related to the spin matrices of quantum mechanics. This allows them to derive relativistic wave equations.[6]

See also

Associative algebras

Lie groups

References

- 1 2 E.P. Wigner (1959). Group theory and its application to the quantum mechanics of atomic spectra. Pure and applied physics. Academic press. p. 73.

- ↑ W.K. Tung (1985). Group Theory in Physics. World Scientific. p. 32. ISBN 997-1966-565.

- ↑ W.K. Tung (1985). Group Theory in Physics. World Scientific. p. 33. ISBN 997-1966-565.

- 1 2 Serre, Jean-Pierre (1977). Linear Representations of Finite Groups. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0387901909.

- ↑ "A Dictionary of Chemistry, Answers.com" (6th ed.). Oxford Dictionary of Chemistry.

- ↑ T. Jaroszewicz; P.S Kurzepa (1992). "Geometry of spacetime propagation of spinning particles". Annals of Physics. California, USA. 216: 226–267. Bibcode:1992AnPhy.216..226J. doi:10.1016/0003-4916(92)90176-M.

Books

- H. Weyl (1950). The theory of groups and quantum mechanics. Courier Dover Publications. p. 203.

- A. D. Boardman; D. E. O'Conner; P. A. Young (1973). Symmetry and its applications in science. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0-07-084011-3.

- V. Heine (2007). Group theory in quantum mechanics: an introduction to its present usage. Dover. ISBN 0-07-084011-3.

- V. Heine (1993). Group Theory in Quantum Mechanics: An Introduction to Its Present Usage. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 048-6675-858.

- E. Abers (2004). Quantum Mechanics. Addison Wesley. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-13-146100-0.

- B. R. Martin, G.Shaw. Particle Physics (3rd ed.). Manchester Physics Series, John Wiley & Sons. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-470-03294-7.

- Weinberg, S (1995), The Quantum Theory of Fields, 1, Cambridge university press, pp. 230–231, ISBN 0-521-55001-7

- Weinberg, S (1996), The Quantum Theory of Fields, 2, Cambridge university press, ISBN 0-521-55002-5

- Weinberg, S (2000), The Quantum Theory of Fields, 3, Cambridge university press, ISBN 0-521-66000-9

- R. Penrose (2007). The Road to Reality. Vintage books. ISBN 0-679-77631-1.

- P. W. Atkins (1970). Molecular Quantum Mechanics (Parts 1 and 2): An introduction to quantum chemistry. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 125–126. ISBN 0-19-855129-0.

Papers

- Bargmann, V.; Wigner, E. P. (1948). "Group theoretical discussion of relativistic wave equations". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 34 (5): 211–23. Bibcode:1948PNAS...34..211B. doi:10.1073/pnas.34.5.211. PMC 1079095. PMID 16578292.

- E. Wigner (1937). "On Unitary Representations Of The Inhomogeneous Lorentz Group" (PDF). Annals of Mathematics. 40 (1): 149. Bibcode:1989NuPhS...6....9W. doi:10.2307/1968551. JSTOR 1968551.

Further reading

- Artin, Michael (1999). "Noncommutative Rings" (PDF). Chapter V.

External links

- "Commission on Mathematical and Theoretical Crystallography, Summer Schools on Mathematical Crystallography" (PDF). 2010.

- van Beveren, Eef (2012). "Some notes on group theory" (PDF).

- Teleman, Constantin (2005). "Representation Theory" (PDF).

- Finley. "Some Notes on Young Tableaux as useful for irreps of su(n)" (PDF).

- Hunt (2008). "Irreducible Representation (IR) Symmetry Labels" (PDF).

- Dermisek, Radovan (2008). "Representations of Lorentz Group" (PDF).

- Maciejko, Joseph (2007). "Representations of Lorentz and Poincaré groups" (PDF).

- Woit, Peter (2015). "Quantum Mechanics for Mathematicians: Representations of the Lorentz Group" (PDF). , see chapter 40

- Drake, Kyle; Feinberg, Michael; Guild, David; Turetsky, Emma (2009). "Representations of the Symmetry Group of Spacetime" (PDF).

- Finley. "Lie Algebra for the Poincaré, and Lorentz, Groups" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-06-17.

- Bekaert, Xavier; Boulanger, Niclas (2006). "The unitary representations of the Poincaré group in any spacetime dimension". arXiv:hep-th/0611263.

- "McGraw-Hill dictionary of scientific and technical terms".