International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants

| Union internationale pour la protection des obtentions végétales | |

UPOV Headquarters | |

| Headquarters | Geneva, Switzerland |

|---|---|

Key people |

|

| Website | UPOV.int |

The International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants or UPOV (French: Union internationale pour la protection des obtentions végétales) is an intergovernmental organization with headquarters in Geneva, Switzerland. The current Secretary-General of UPOV is Francis Gurry.[1]

UPOV was established by the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants. The Convention was adopted in Paris in 1961 and revised in 1972, 1978 and 1991. The objective of the Convention is the protection of new varieties of plants by an intellectual property right. By codifying intellectual property for plant breeders, UPOV aims to encourage the development of new varieties of plants for the benefit of society.

For plant breeders' rights to be granted, the new variety must meet four criteria under the rules established by UPOV:[2]

- The new plant must be novel, which means that it must not have been previously marketed in the country where rights are applied for.

- The new plant must be distinct from other available varieties.

- The plants must display homogeneity.

- The trait or traits unique to the new variety must be stable so that the plant remains true to type after repeated cycles of propagation.

Protection can be obtained for a new plant variety (legally defined) however it has been obtained, e.g. through conventional breeding techniques or genetic engineering.

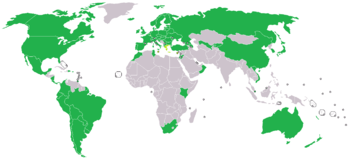

Members

As of October 2, 2015 the following 74 parties were members of UPOV:[3] African Intellectual Property Organisation, Albania, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, the People's Republic of China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Estonia, European Union,[4] Finland, France, Georgia,[5] Germany, Guatemala, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kenya, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Mexico, Moldova, Morocco, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Oman, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Republic of Korea, Romania, Russian Federation, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, Turkey, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, the United States of America (with a reservation),[6] Uruguay, Uzbekistan, and Viet Nam.[7]

The membership to the different versions of the convention is shown below:

| Party | 1961 Convention | 1978 Convention | 1991 Convention | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 October 2005 | ||||

| 25 December 1994 | ||||

| 1 March 1989 | 20 January 2000 | |||

| 14 July 1994 | 1 July 2004 | |||

| 9 December 2004 | ||||

| 5 January 2003 | ||||

| 5 December 1976 | ||||

| 21 May 1999 | ||||

| 23 May 1999 | ||||

| 24 April 1998 | ||||

| 4 March 1991 | 19 July 2015 | |||

| 5 January 1996 | ||||

| 23 April 1999 | ||||

| 13 September 1996 | ||||

| 12 January 2009 | ||||

| 1 September 2001 | ||||

| 1 January 1993 | 24 November 2002 | |||

| 6 October 1968 | 8 November 1981 | 24 April 1998 | ||

| 16 June 2007 | ||||

| 8 August 1997 | ||||

| 24 September 2000 | ||||

| 29 July 2005 | ||||

| 16 April 1993 | 20 July 2001 | |||

| 3 October 1971 | 17 March 1983 | 27 May 2012 | ||

| 29 November 2008 | ||||

| 10 August 1968 | 12 April 1986 | 25 July 1998 | ||

| 16 April 1983 | 1 January 2003 | |||

| 3 May 2006 | ||||

| 8 November 1981 | 8 January 2012 | |||

| 12 December 1979 | 12 May 1984 | 24 April 1998 | ||

| 1 July 1977 | 28 May 1986 | |||

| 3 September 1982 | 24 December 1998 | |||

| 24 October 2004 | ||||

| 13 May 1999 | ||||

| 26 June 2000 | ||||

| 30 August 2002 | ||||

| 10 December 2003 | ||||

| 4 May 2011 | ||||

| 9 August 1997 | ||||

| 28 October 1998 | ||||

| 24 September 2015 | ||||

| 8 October 2006 | ||||

| 10 August 1968 | 2 September 1984 | 1 July 2004 | European Netherlands only | |

| 8 November 1981 | ||||

| 6 September 2001 | ||||

| 13 September 1993 | ||||

| OAPI | 24 April 1998 | |||

| 23 May 1999 | 22 November 2012 | |||

| 8 February 1997 | ||||

| 8 August 2011 | ||||

| 11 November 1989 | 15 August 2003 | |||

| 14 October 1995 | ||||

| 16 March 2001 | ||||

| 24 April 1998 | ||||

| 5 January 2013 | ||||

| 30 July 2004 | ||||

| 1 January 1993 | 12 June 2009 | |||

| 29 July 1999 | ||||

| 6 November 1977 | 8 November 1981 | |||

| 7 January 2002 | ||||

| 18 May 1980 | 18 July 2007 | |||

| 17 December 1971 | 1 January 1983 | 24 April 1998 | ||

| 10 July 1977 | 8 November 1981 | 1 September 2008 | ||

| 30 January 1998 | ||||

| 31 August 2003 | ||||

| 18 November 2007 | ||||

| 3 November 1995 | 19 January 2007 | |||

| 10 August 1968 | 24 September 1983 | 3 January 1999 | ||

| 8 November 1981 | 22 February 1999 | |||

| 13 November 1994 | ||||

| 14 November 2004 | ||||

| 24 December 2006 |

System of protection

The Convention defines both how the organization must be governed and run, and the basic concepts of plant variety protection that must be included in the domestic laws of the members of the Union. These concepts include:[8]

- The criteria for new varieties to be protected: novelty, distinctness, uniformity, and stability.

- The process for application for a grant.

- Intellectual property rights conferred to an approved breeder.

- Exceptions to the rights conferred to the breeder.

- Required duration of breeder's right.

- Events in which a breeder's rights must be declared null and void.

In order to be granted breeder's rights, the variety in question must be shown to be new. This means that the plant variety cannot have previously been available for more than one year in the applicant’s country, or for more than four years in any other country or territory. The variety must also be distinct (D), that is, easily distinguishable through certain characteristics from any other known variety (protected or otherwise). The other two criteria, uniformity (U) and stability (S), mean that individual plants of the new variety must show no more variation in the relevant characteristics than one would naturally expect to see, and that future generations of the variety through various propagation means must continue to show the relevant distinguishing characteristics. The UPOV offers general guidelines for DUS testing.[9]

A breeder can apply for rights for a new variety in any union member country, and can file in as many countries as desired without waiting for a result from previous applications. Protection only applies in the country in which it was granted, so there are no reciprocal protections unless otherwise agreed by the countries in question. There is a right of priority, and the application date of the first application filed in any country is the date used in determining priority.

The rights conferred to the breeder are similar to those of copyright in the United States, in that they protect both the breeder's financial interests in the variety and his recognition for achievement and labor in the breeding process. The breeder must authorize any actions taken in propagating the new variety, including selling and marketing, importing and exporting, keeping stock of, and reproducing. This means that the breeder can, for example, require a licensing fee for any company interested in reproducing his variety for sale. The breeder also has the right to name the new variety, based on certain guidelines that prevent the name from being deliberately misleading or too similar to another variety's name.

There are explicit exceptions to the rights of the breeder, known as the "breeder's exemption clause", that make it unnecessary to receive authorization for the use of a protected variety where those rights interfere in the use of the variety for a private individual's non-monetary benefit, or the use of the variety for further research. For example, the breeder's rights do not cover the use of the variety for subsistence farming, though they do cover the use of the variety for cash crop farming. Additionally, the breeder's authorization is not required to use a protected variety for experimental purposes, or for breeding other varieties, as long as the new varieties are not "essentially derivative" of the protected variety.[8]

The Convention specifies that the breeder's right must be granted for at least 20 years from grant date, except in the case of varieties of trees or vines, in which case the duration must be at least 25 years.[8]

Finally, there are provisions for how to negate granted breeders' rights if the rights are determined to be unfounded. That is, if it is discovered after the application has been granted that the variety is not actually novel or distinct, or if it is discovered to not be uniform or stable, the breeder's rights are nullified. In addition, if it is discovered that the person who applied for protection of the variety is not the actual breeder, the rights are nullified unless they can be transferred to the proper person. If it is discovered after a period of protection that the variety is no longer uniform and stable, the breeder's rights are canceled.

Genetically modified plant varieties

The UPOV has been updated several times to reflect changing technology and increased understanding of how plant variety intellectual property protection must work. The last revision was in 1991, and specifically mentioned genetic engineering only insofar as it is a method of creating variation.[10] Under the UPOV Convention alone, genetically modified crops and the intellectual property rights granted to them are no different from the intellectual property rights granted for traditionally bred varieties. It is important to note that this necessarily includes the ability to use protected varieties for subsistence farming and for research.

In October 2004, two joint Symposia were held in Geneva with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). These Symposia were the WIPO-UPOV Symposium on Intellectual Property Rights in Plant Biotechnology (24 October 2003) and the WIPO-UPOV Symposium on the Co-Existence of Patents and Plant Breeders’ Rights in the Promotion of Biotechnological Developments (25 October 2003). No new policy was created at either of these events, but a consensus emerged that both patents and plant-breeders' rights must combine to promote plant biotechnology.[11]

As a policy matter, the UPOV is known to consider open and un-restricted access to the genetic resources of protected plant varieties to be important to the continued development of new varieties.[12] This opinion is indicated in the "breeders' exemption" clause of the Convention, as described above, and was reinforced in October 2005 in a reply to a notification from the Convention on Biological Diversity.

In April 2003, the Convention on Biological Diversity asked the UPOV for comment on the use of Genetic Use Restriction Technologies (also known pejoratively as 'terminator genes') as they relate to the promotion of intellectual property rights. In the summary of their response, the UPOV stated that intellectual property protection is necessary because breeders must have the ability to recoup their money and labor investment in creating new varieties, and in that light, plants with 'terminator genes' may still be accepted for protection if they meet the other criteria. However, the UPOV comment states that the Convention and its system of protection is sufficient to protect intellectual property rights, and that with proper legal protections in place, technologies like 'terminator genes' should not be necessary.[13]

Development and public interest concerns

Whether or not UPOV negatively affects agriculture in developing countries is much debated. It is argued that UPOV's focus on patents for plant varieties hurts farmers, in that it does not allow them to use saved seed or that of protected varieties. Countries with strong farmers' rights, such as India, cannot comply to all aspects of UPOV. François Meienberg is of this opinion, and writes that the UPOV system has disadvantages, especially for developing countries, and that "at some point, protection starts to thwart development".[14]

On the other hand, Rolf Jördens argues that plant variety protection is necessary. He believes that by joining UPOV, developing countries will have more access to new and improved varieties (better yielding, stronger resistance) instead of depending on old varieties or landraces, thus helping fight poverty and feed the growing world population.[15]

Empirical evidence to support either point of view is lacking. However, two things are clear.

First, UPOV supports an agricultural system that is clearly export-oriented. In other word, developing countries moving towards UPOV-consistent systems tend to favour breeders who are producing for export. The example of Kenya is telling in this regard, as UPOV's own study points out, the majority of varieties are owned by foreign producers and are horticultural crops, clearly destined for export. An over-heavy dependence on agriculture for export is increasingly recognized as being unwise.[16][17]

Second, given the lack of empirical evidence to support this, it would make sense to encourage debate, exchange of knowledge and research on the impacts of UPOV type plant variety protection on farming, food, human rights and other public interest objectives. However, UPOV seems to be resisting this, for instance by keeping meetings secret, not making its documents available and [refusing farmers' organisations observer status with UPOV.[18] A recent study by Professor Graham Dutfield[19] exploring the role of UPOV concluded that UPOV's governance falls short in many different ways. In addition, UPOV officials know very little about actual farming. They may know about breeding and favour commercial breeders, but this is not the same as knowing about how small-scale farmers actually develop new varieties and produce them. The UPOV system thus favours commercial breeders over farmers and producers, and private interests over public interests. The UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, Olivier De Schutter, came to similar findings in his study of UPOV in 2009. He found that IP-related monopoly rights could cause poor farmers to become “increasingly dependent on expensive inputs” and at risk of indebtedness. Further, the system risks neglecting poor farmers’ needs in favour of agribusiness needs, jeopardising traditional systems of seed saving and exchange, and losing biodiversity to “the uniformization encouraged by the spread of commercial varieties.[20]

See also

- Community Plant Variety Office (CPVO)

- Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970

- Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers' Rights Act, 2001

- "Plant variety" (the legal term) vs. "variety" (the botanical taxonomy term)

Notes and references

- ↑ NEW SECRETARY-GENERAL OUTLINES FUTURE PRIORITIES FOR UPOV, UPOV Press Release No. 77, Geneva, October 30, 2008 Archived March 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "About the UPOV System of Plant Variety Protection". UPOV.int. Union internationale pour la protection des obtentions végétales. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- ↑ List of UPOV Members published by (PDF )

- ↑ The European Community was the first intergovernmental organization to join; The European Union is its legal successor.

- ↑ UPOV Notification No. 106, International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, Accession by Georgia, October 29, 2008.

- ↑ "UPOV Notification No. 69: Ratification by the United States of America of the 1991 Act". UPOV. 22 January 1999. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ UPOV web site, Members of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants, UPOV Convention (1961), as revised at Geneva (1972, 1978 and 1991) Status on May 12, 2009. Consulted on June 26, 2009. Archived January 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 UPOV System of Protection. http://www.upov.int/en/about/upov_system.htm Archived 2005-12-18 at the Wayback Machine.. 2002.

- ↑ UPOV (19 April 2002). General introduction to the examination of distinctness, uniformity and stability and the development of harmonized descriptions of new varieties of plants (PDF) (Report). UPOV. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-08-21. Retrieved 2006-08-15. UPOV Convention: 1991 Act, Article 14, Section 5c. 1991.

- ↑ http://www.upov.int/en/documents/Symposium2003/intro_index.html%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D WIPO-UPOV Symposium. 2003.

- ↑ http://www.upov.int/en/about/pdf/cbd_respons_oct_31_2005.pdf Jordens, Rolf. Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit-Sharing. October 31, 2005. p 4. Archived May 26, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20050504231127/http://www.upov.int/en/about/pdf/gurts_11april2003.pdf Position of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) concerning Decision VI/5 of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). April 11, 2003. p 2.

- ↑ François Meienberg: Infringement of farmers' rights D+C, 2010/04, Focus, Page 156-158 Archived January 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Rolf Jördens: Legal framework for investment D+C, 2010/04, Focus, Page 150-153 Archived January 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ George Kent: Africa's food security under globalization Archived 2011-10-26 at the Wayback Machine. African Journal of Food and Nutritional Sciences: Vol. 2 No. 1 March 2002

- ↑ Joseph Stiglitz: Causes of hunger are related to poverty globalissues.org, 2010

- ↑ UPOV to decide on farmers’ and civil society participation in its sessions European Coordination Via Campesina (ECVC) & Association for Plant Breeding for the Benefit of Society (APBREBES) Archived January 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Graham Dutfield: Food, Biological Diversity and Intellectual Property – The Role of the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV) Archived 2012-03-23 at the Wayback Machine. 2011

- ↑ UN Special Rapporteur on the right to food