Igo Hatsuyōron

| Author | Inoue Dōsetsu Inseki |

|---|---|

| Original title | 囲碁 発陽論 |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

| Genre | Collection of Tsumego |

Publication date | 1713 |

Igo Hatsuyōron (囲碁 発陽論, literally Literally: From yang production in the game of go, often abbreviated Hatsuyōron) is a collection of 183 go problems (mostly tsumego), compiled in 1713 by the Japanese go master Inoue Dōsetsu Inseki.

Until the end of the XIXth century, the Hatsuyōron remains a closely guarded secret of the Inoue house, where he used to drive the best disciples at the tactics. It becomes public after the collapse of the Four go houses; several incorrect editions are published, before the discovery in 1982 of a copy that is close to the original now lost.

Igo Hatsuyōron is considered the most difficult of such collections, and as such is still used for training Go professionals. It contains many problems so complex that false or incomplete solutions were given in the first editions, and in particular an exceptional problem by its theme and its depth, rediscovered in 1982, and which is not yet completely solved in 2015.

History

Inoue Dōsetsu Inseki, the fourth head of the Inoue house and Meijin from 1708 to his death in 1719, is best known for his role as guardian of the young Dōchi after the death of his master Dōsaku[1]; his exceptional skill as a composer of go problems is only discovered after the collapse of the Four go houses from 1868, during the Meiji Restoration[N 1].

In 1713, Dōsetsu compiled Igo Hatsuyōron (Japanese: 囲 碁 発 陽 論, simplified Chinese: 围棋 发 阳 论, pinyin: wéiqí fāyánglùn, literally meaning: From yang production in the game of go[N 2]) from a collection of more than 1500 problems, many of which are compounded by him or improved from previous problems[2]. The book is designed to serve the training of the best disciples, and to this end contains only the problems, without any indication on their solution[N 3]. For more than 150 years, he is kept secret, being studied only one problem at a time, under the direct control of the Inoue house; the very existence of the book is ignored by the other three houses (Hon'inbō, Hayashi and Yasui)[2].

The Hatsuyōron becomes public after 1868 (passing hand in hand in the Hon'inbō house[2]), and a first edition was published in 1914 by Hon'inbō Shūsai, enriched with solutions and comments; from that moment, the book acquires its reputation of the "most difficult collection of go problems"[3]. Two other editions, mostly from Shūsai, but improving and detailing the solutions, appeared in 1953 (under the direction of Hideyuki Fujisawa) and in 1980 (under the direction of Utaro Hashimoto). These editions, however, are based not on the original manuscript (which is thought to have been destroyed in a fire[2]), but on incorrect copies, in which some problems from Xuanxuan Qijing (the oldest Chinese classics) slipped.

In 1982, Araki Naomi discovers a previous copy[4] apparently containing only the problems of the original version, including two previously unknown; the responsibility of a new edition is entrusted to Hideyuki Fujisawa (then Kisei), which causes it to look more closely at one of these two problems (the number 120), to conclude that this is "The most difficult problem ever composed"; he publishes an article on this subject[5], detailing the remarks of the complete edition.

From 1988, an analysis of the solutions of the 1982 edition by Chinese professionals leads them to question some of the Japanese conclusions; Cheng Xiaoliu[N 4] published in 2010 a revised edition of their comments, under the title of Wéiqí Fāyánglùn Yánjiū (围棋 发 阳 论 研究, Research on Hatsuyōron)[6].

Content

The exact initial composition of the collection is unknown, and the order of the problems is probably corrupt; Cheng Xiaoliu note that in the edition of 1914, the first problem is no solution[N 5], and suggests that it could have been placed at the head of a rival schools, to discredit the book [7].

The copy used in the 1982 edition, however, is considered fairly close to the original work composed by Dōsetsu[2], and also contains a written postface by his hand, in which he explains in particular the meaning of the title of the collection[N 2] and how it should be studied[N 3]; this copy contains 183 problems, divided into six sections[N 6]:

- live (30 problems);

- kill (46 problems, among which 13 problems of sacrifice of blocks (nakade and ishinoshita) grouped at the end of section);

- ko battles (51 problems);

- freedom races (semeai) (36 problems);

- stairs (shichō[N 7]) (12 problems);

- various problems (8 problems).

Most of these problems (except perhaps those of the last two sections) can be considered life and death problems; the Hatsuyōron does not deal with issues of strategy, but only aims to develop the capacity tactical players [N 3]. These problems, however, are not "realistic" in the sense that they come from situations that can be partially met; they seek above all to show extraordinary blows and maneuvers, and to oblige one to envisage well-hidden resistances; moreover, one of the conventions chosen for these problems is that "all the stones of the utterance must be useful"[8][N 8], which Dōsetsu sometimes exploits for additional artistic effects, as shown by the example of problem 43, shown in the previous section.

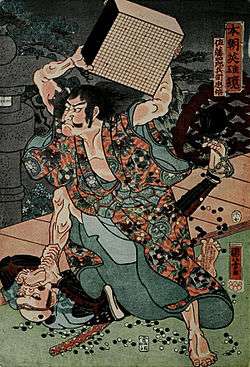

Almost all these problems are at the level of professional players (and are still used in their training)[2], that is to say that an amateur player cannot solve them in a game situation, without laying stones; some of them are so difficult that they are probably insoluble under these conditions, even by the best players; this is particularly the case of the seven problems covering the entire goban, including the astonishing problem 76 represented above, which Nakayama attributes to Dōsaku[N 9], and to which he gives the title "the bait swallows the fish"[9].

The most difficult problem ever composed

In 1982, a copy of the xixth century is found, containing two issues not included in previous editions[4]. The manuscript is entrusted to Fujisawa Hideyuki (then Kisei) to make a new edition commented on it, but, assuming that the problem 120 should have been copied badly, he hands it over to one of his disciples, Yasuda Yasutoshi, to try to rectify it[10]. He finally sees the unprecedented sacrifice maneuver which is the main theme of the problem, and after about a thousand hours of collective work[N 10], Fujisawa believes that the problem is solved, and publishes its solution, translated in GB World number 29 under the title The Most Difficult Problem Ever, accompanied by a complimentary comment, mentioning "the surprising novelty of the theme and forms, the precise calculation of the fights, and the delicate balance of trade and score, all of which make this unique problem the masterpiece of a lifetime"[11].

The statement of the problem (figure on the right) is a position that could almost be drawn from a real game[N 11], accompanied by the caption "Black plays and wins the game"[N 12]; the solution is, in the main variant, a long series of battles using tactics unthinkable even for professional players, containing in particular a sacrifice of twenty black stones that White is obliged to refuse as long as possible[N 13], and completing, after more than one hundred and fifty strokes, end-game subtleties (yose) finally winning Black one or two points[12].

This analysis is not disputed by the Chinese edition of Hatsuyōron in 1988, although this edition contains an improvement of the main sequence, bringing the advance of Black to three points. But in 2005, a German amateur player, Joachim Meinhardt, discovers an unexpected resistance of White[4]; confirmed by professionals[N 14], this line of play questions all previous solutions. At the end of 2007, another German amateur, Thomas Redecker, observes that a seemingly mediocre blow of Black, which had never been envisaged until then, played at the opportune moment (at stroke 67) of the main variant), perhaps allows to save the situation, but it does not reach at this time to make study this maneuver by professionals, and decides to publish all of its analyzes on a website, then in form of book[13]. They are enriched (first with the help of a wiki[14]) by many amateur and professional players, and a winning line for Black is confirmed by professional players starting in 2012, but, in 2015, new variations appear again[14], the problem cannot be considered as completely resolved[N 15].

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ For example, The Go Player's ALMANAC, which relies for its historic part of documents of the Edo period, does not even mention the Hatsuyōron in its section on Dosetsu.

- 1 2 Since the rediscovery of the postface of Dōsetsu in 1982, we know that for him, in the context of go tactics, the yin represents the shape of the stones, and the yang changes the relations between the groups thanks to remarkable tactical moves, tesujis.

- 1 2 3 In his postface, Dōsetsu insists on the necessity, for the study of these problems to bear fruit, to give no indication about them, not even the objective to reach.

- ↑ 6th dan Chinese Professional.

- ↑ In the 1982 edition, this issue bears the number 17 and, according to Cheng Xiaoliu, deserves the sarcastic caption: "Black plays and dies".

- ↑ This distribution (as well as numbering problems) seems to have been introduced in the 1982 edition by Fujisawa Hideyuki.

- ↑ Also classified in this section shichōs "fuzzy" (yurumi shicho), that is to say the sequences where the fleeing group runs an important part of goban, but failed to win freedom.

- ↑ This convention sometimes makes the resolution easier, since we know that we have not yet perceived all the subtleties of the position if there remains a stone whose role is not understood; it also ensures that there are not really false intentional tracks in these statements.

- ↑ An improvement of the problem 76, carrying the sacrifice to 83 stones, was published (in the Genran) by Akaboshi Intetsu in 1833; we can think that this problem at least was not considered secret at that time.

- ↑ Which is unusually long for professionals: analyzing this question, Harry Fearnley, a British 2nd dan, for example says, discussing the shots yose a secondary variant of the problem 120 with a Korean professional, she showed him immediately the correct sequence... that his group of fans had taken several weeks to determine (Igo Hatsuyoron Problem 120, p. 138).

- ↑ Only a few stones on the first line would be difficult to justify if it was a real part.

- ↑ In fact, this statement was added by Fujisawa; in accordance with the principles stated by Dōsetsu in his postface, the original manuscript contained no indication of the purpose of the problem.

- ↑ These stones are on the border of a temporary seki, in a rare configuration known as hanezeki; an accurate analysis of the reasons for which White refuses to accept this poisoned gift is found in the corresponding article of Sensei 's Library; more detailed calculations of the consequences of capture can be found, for example, in Harry Fearnley's study, p. 27.

- ↑ Cheng Xiaoliu carefully analyzing this resistance (not attributed to Joachim Meinhardt) in the Chinese edition of 2010 (Cheng 2010, p. 386).

- ↑ The complete resolution of a tsumego problem, according to the criteria of professional players, requires that all essential variants have been explored, and not only that the statement is satisfied (here, that Black wins the game), but that the result is the best possible, and so in this case that Black has the greatest possible advance against the best white resistance.

References

- ↑ The Go Player's ALMANAC, Ishi Press, June 1992, p. 24-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Yutopian 1997, p. iii to vii (preface); some of this information comes from the postface of Dōsetsu rediscovered in 1982.

- ↑ Igo Hatsuyōron is hailed as the highest authority in tsumego (Yutopian 1997, p.1).

- 1 2 3 (Redecker 2011, p. 9).

- ↑ Fujisawa 1982, p. 49.

- ↑ Cheng 2010.

- ↑ Yutopian 1997, p. 41.

- ↑ Yutopian 1997, p. 158.

- ↑ The bait catches the fish, in Noriyuki Nakayama, The Treasure Chest Enigma, Slate and Shell, 2005, p. 180.

- ↑ Redecker 2011, p. 135.

- ↑ Fujisawa 1982, p. 49.

- ↑ Redecker 2011, p. 52-53

- ↑ Redecker 2011

- 1 2 Collaborative website maintained by Thomas Redecker; in 2015, this site was redesigned for a paper publication, and its content is now available at volume I (solution) and volume II volume II (theoretical analyzes).