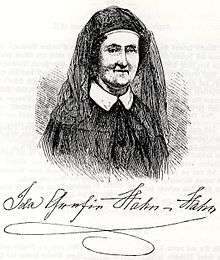

Ida, Countess von Hahn-Hahn

Countess Ida von Hahn-Hahn (German: Ida Gräfin von Hahn-Hahn; 22 June 1805 – 12 January 1880) was a German author from a wealthy family who lost their fortune because of her father's eccentric spending. She defied convention by living with Adolf von Bystram unmarried for 21 years. Her writings about the German aristocracy were greatly favored by the general public of her time. Ida von Hahn-Hahn often wrote about the tragedies of the soul and was influenced by the French poet, George Sand. She "was an indefatigable campaigner for the emancipation of women"[1] and her writings include many strong female characters.[2][3]

Biography

She was born at Tressow, in the duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. She was the daughter of Carl Friedrich Graf (Count) von Hahn (1782 – 21 May 1857 Altona), who was well known for his enthusiasm for stage productions, upon which he squandered a large portion of his fortune. In his old age, he was obliged to support himself by managing a provincial company, and died in poverty. In 1826, Ida married her wealthy cousin Friedrich Wilhelm Adolph Graf von Hahn, which gave her the doubled name. With him she had an extremely unhappy life, and in 1829 her husband's irregularities led to a divorce.[4][5] She spent the years after her divorce ignoring social norms by traveling and living with Baron Adolf von Bystram.[1] Bystram encouraged her to write about their travels across Europe and the Near East.[2]

In 1847 the author drew upon herself the merciless ridicule of Fanny Lewald who "attacked her as a self-indulgent aristocrat indifferent to the plight of the poor."[3] After the revolutions of 1848 and the death of Adolf von Bystram in 1849, she embraced the Roman Catholic religion in 1850. Hahn-Hahn justified her step in a polemical work entitled Von Babylon nach Jerusalem (1851), which elicited a vigorous reply from Heinrich Abeken, and from several others as well.[4]

In November 1852, she retired into a convent at Angers, which she however soon left, taking up residence in Mainz as a "layperson in a convent she had co-founded for "fallen" girls."[2] Hahn-Hahn devoted herself to the reformation of outcasts of her own sex, and wrote several works, among which are: Bilder aus der Geschichte der Kirche (3 vols., 1856-'64); Peregrina (1864); and Eudoxia (1868).[5]

Writings

For many years, her novels were the most popular works of fiction in aristocratic circles; many of her later publications, however, passed unnoticed as mere religious manifestoes. Ulrich and Gräfin Faustine, both published in 1841, mark the culmination of her power; but Sigismund Forster (1843), Cecil (1844), Sibylle (1846) and Maria Regina (1860) also obtained considerable popularity. For several years, the countess continued to produce novels bearing a certain subjective resemblance to those of George Sand, but less hostile to social institutions, and dealing almost exclusively with aristocratic society.[1]

Her collected works, Gesammelte Werke, with an introduction by Otto von Schaching, were published in two series, 45 volumes in all (Regensburg, 1903–1904).[6]

Gräfin Faustine

Gräfin Faustine or Countess Faustine travels to the Orient and ends up in "a cloister to expiate her sins".[1] Countess Faustine is a female Don Joan set in a world of adultery.[3] [6]

Catholic writings

After converting to Roman Catholic, Hahn-Hahn began writing to show lost souls they way to the Church in Rome.[1]

Publications

Countess von Hahn-Hahn's published works as cited by An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers.[1]

- Gedichte [Poems] (1841)

- Gedichte [Poems], 1835.

- Lieder und Gedichte [Songs and Poems], 1837.

- Ilda Schönholm [Ilda Schönholm], 1838.

- Gräfin Faustine [Countess Faustine], 1841.

- Ulrish, 1841.

- Gräfin Cecil [Countess Cecil], 1844.

- Aus der Gesselschaft [From the Realm of Society], 1845.

- Sybille, 1846.

- Von Babylon nach Jerusalem [From Babylon to Jerusalem], 1851.

- Die Liebhaber des Kreuzes [The Lover of the Cross], 1852.

- Maria Regina, 1860.

- Peregrin, 1864.

- Die Glocknerstochter [The Bell-ringer's Daughters], 1871.

- Vergib uns unsere Schuld [Forgive Us Our Trespasses], 1871.

- Wahl und Führung [Choice and Leading], 1878.

- Gesamtausgabe [Complete Works: Protestant Works], 21 volumes, 1851.

- Gesammelte Werke [Collected Works: Catholic Works], 45 volumes, 1930.

Further reading

- Gert Oberembt, Ida Gräfin Hahn-Hahn, Weltschmerz und Ultramontanismus (Bonn, 1980)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wilson, Katharina M. (1991). An Encyclopedia of Continental Women Writers. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc.

- 1 2 3 Argyle, Gisela (2007). "THE HORROR AND THE PLEASURE OF UN-ENGLISH FICTION: IDA VON HAHN-HAHN AND FANNY LEWALD IN ENGLAND". Comparative Literature Studies. 44 (1): 144–165.

- 1 2 3 Kontje, Todd (1998). Women, the Novel, and the German Nation 1771-1871. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521631106.

- 1 2 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "

- 1 2 "

- 1 2 Chambers, Helen (2007). Humor and Irony in Nineteenth-Century German Women's Writing. Rochester, New York: Camden House. ISBN 9781571133045.

Notes

- Regarding personal names: Gräfin is a title, translated as Countess, not a first or middle name. The masculine form is Graf.

- Heinrich Keiter, Ida Gräfin Hahn-Hahn, ein Lebens- und Literaturbild (Würzburg, 1879–80)

- Paul Haffner, Gräfin Ida Hahn-Hahn, eine psychologische Studie (Frankfurt, 1880)

- Alinda Jacoby, Ida Gräfin Hahn-Hahn, Novellistisches Lebensbild (Mainz, 1894)

- Cayzer, Herlinde. Feminist Awakening in Ida von Hahn-Hahn's 'Graefin Faustine' and Luise Muehlbach's 'Aphra Behn.' (Brisbane, 2007).