Huygens–Fresnel principle

The Huygens–Fresnel principle (named after Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens and French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel) is a method of analysis applied to problems of wave propagation both in the far-field limit and in near-field diffraction.

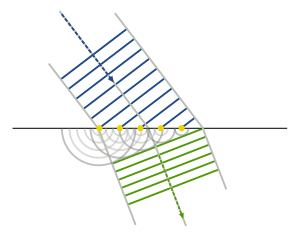

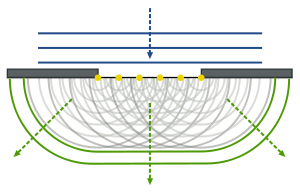

It states that every point on a wavefront is itself the source of spherical wavelets.[1] The sum of these spherical wavelets forms the wavefront.

History

In 1678, Huygens[2] proposed that every point to which a luminous disturbance reaches becomes a source of a spherical wave; the sum of these secondary waves determines the form of the wave at any subsequent time. He assumed that the secondary waves travelled only in the "forward" direction and it is not explained in the theory why this is the case. He was able to provide a qualitative explanation of linear and spherical wave propagation, and to derive the laws of reflection and refraction using this principle, but could not explain the deviations from rectilinear propagation that occur when light encounters edges, apertures and screens, commonly known as diffraction effects.[3] The resolution of this error was finally explained by David A.B. Miller in 1991.[4] The resolution is that the source is a dipole (not the monopole assumed by Huygens), which cancels in the reflected direction.

In 1818, Fresnel[5] showed that Huygens' principle, together with his own principle of interference could explain both the rectilinear propagation of light and also diffraction effects. To obtain agreement with experimental results, he had to include additional arbitrary assumptions about the phase and amplitude of the secondary waves, and also an obliquity factor. These assumptions have no obvious physical foundation but led to predictions that agreed with many experimental observations, including the Arago spot.

Poisson was a member of the French Academy, which reviewed Fresnel's work.[6] He used Fresnel's theory to predict that a bright spot ought to appear in the center of the shadow of a small disc, and deduced from this that the theory was incorrect. However, Arago, another member of the committee, performed the experiment and showed that the prediction was correct. (Lisle had observed this fifty years earlier.[3]) This was one of the investigations that led to the victory of the wave theory of light over the then predominant corpuscular theory.

The Huygens–Fresnel principle provides a reasonable basis for understanding and predicting the classical wave propagation of light. However, there are limitations to the principle, and not all experts agree that it is an accurate representation of reality—for instance, Melvin Schwartz argued that "Huygens' principle actually does give the right answer but for the wrong reasons".[7] See Huygens' Theory and the Modern Photon Wavefunction below.

Kirchhoff's diffraction formula provides a rigorous mathematical foundation for diffraction, based on the wave equation. The arbitrary assumptions made by Fresnel to arrive at the Huygens–Fresnel equation emerge automatically from the mathematics in this derivation.[8]

A simple example of the operation of the principle can be seen when an open doorway connects two rooms and a sound is produced in a remote corner of one of them. A person in the other room will hear the sound as if it originated at the doorway. As far as the second room is concerned, the vibrating air in the doorway is the source of the sound.

Mathematical expression of the principle

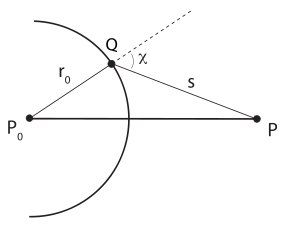

Consider the case of a point source located at a point P0, vibrating at a frequency f. The disturbance may be described by a complex variable U0 known as the complex amplitude. It produces a spherical wave with wavelength λ, wavenumber k = 2π/λ. The complex amplitude of the primary wave at the point Q located at a distance r0 from P0 is given by:

since the magnitude decreases in inverse proportion to the distance travelled, and the phase changes as k times the distance travelled.

Using Huygens' theory and the principle of superposition of waves, the complex amplitude at a further point P is found by summing the contributions from each point on the sphere of radius r0. In order to get agreement with experimental results, Fresnel found that the individual contributions from the secondary waves on the sphere had to be multiplied by a constant, −i/λ, and by an additional inclination factor, K(χ). The first assumption means that the secondary waves oscillate at a quarter of a cycle out of phase with respect to the primary wave, and that the magnitude of the secondary waves are in a ratio of 1:λ to the primary wave. He also assumed that K(χ) had a maximum value when χ = 0, and was equal to zero when χ = π/2. The complex amplitude at P is then given by:

where S describes the surface of the sphere, and s is the distance between Q and P.

Fresnel used a zone construction method to find approximate values of K for the different zones,[6] which enabled him to make predictions that were in agreement with experimental results.

The various assumptions made by Fresnel emerge automatically in Kirchhoff's diffraction formula,[6] to which the Huygens–Fresnel principle can be considered to be an approximation. Kirchhoff gave the following expression for K(χ):

K has a maximum value at χ = 0 as in the Huygens–Fresnel principle; however, K is not equal to zero at χ = π/2.

Huygens' theory and the modern photon wavefunction

Huygens' theory served as a fundamental explanation of the wave nature of light interference and was further developed by Fresnel and Young but did not fully resolve all observations such as the low-intensity double-slit experiment that was first performed by G. I. Taylor in 1909, see double-slit experiment. It was not until the early, and mid-1900s that quantum theory discussions, particularly the early discussions at the 1927 Brussels Solvay Conference, where Louis de Broglie proposed his de Broglie hypothesis that the photon is guided by a wavefunction.[9] The wavefunction presents a much different explanation of the observed light and dark bands in a double slit experiment. In this conception, the photon follows a path which is a random choice of one of many possible paths. These possible paths form the pattern: in dark areas, no photons are landing, and in bright areas, many photons are landing. The set of possible photon paths is determined by the surroundings: the photon's originating point (atom), the slit, and the screen. The wavefunction is a solution to this geometry. The wavefunction approach was further proven by additional double-slit experiments in Italy and Japan in the 1970s and 1980s with electrons.[10]

Huygens' principle and quantum field theory

Huygens' principle can be seen as a consequence of the homogeneity of space—the space is uniform in all locations.[11] Any disturbance created in a sufficiently small region of homogenous space (or in a homogenous medium) propagates from that region in all geodesic directions. The waves produced by this disturbance, in turn, create disturbances in other regions, and so on. The superposition of all the waves results in the observed pattern of wave propagation.

Homogeneity of space is fundamental to quantum field theory (QFT) where the wave function of any object propagates along all available unobstructed paths. When integrated along all possible paths, with a phase factor proportional to the action, the interference of the wave-functions correctly predicts observable phenomena. Every point on the wavefront acts as the source of secondary wavelets that spread out in the light cone with the same speed as the wave. The new wavefront is found by constructing the surface tangent to the secondary wavelets.

In other spatial dimensions

In 1900, Jacques Hadamard observed that Huygens' principle was broken when the number of spatial dimensions is even.[12][13][14] From this, he developed a set of conjectures that remain an active topic of research.[15][16] In particular, it has been discovered that Huygens' principle holds on a large class of homogenous spaces derived from the Coxeter group (so, for example, the Weyl groups of simple Lie algebras).[11][17]

The traditional statement of Huygens' principle for the D'Alembertian gives rise to the KdV hierarchy; analogously, the Dirac operator gives rise to the AKNS hierarchy.[18][19]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Huygens' principle. |

References

- ↑ "Huygens' Principle". MathPages. Retrieved 2017-10-03.

- ↑ Chr. Huygens, Traité de la Lumière (drafted 1678; published in Leyden by Van der Aa, 1690), translated by Silvanus P. Thompson as Treatise on Light (London: Macmillan, 1912; Project Gutenberg edition, 2005), p.19.

- 1 2 OS Heavens and RW Ditchburn, Insight into Optics, 1987, Wiley & Sons, Chichester ISBN 0-471-92769-4

- ↑ David A. B. Miller Huygens's wave propagation principle corrected, Optics Letters 16, pp. 1370-2 (1991). doi:10.1364/OL.16.001370

- ↑ A. Fresnel, "Mémoire sur la diffraction de la lumière" (deposited 1818, "crowned" 1819), in Oeuvres complètes (Paris: Imprimerie impériale, 1866–70), vol.1, pp. 247–363; partly translated as "Fresnel's prize memoir on the diffraction of light", in H. Crew (ed.), The Wave Theory of Light: Memoirs by Huygens, Young and Fresnel, American Book Co., 1900, archive.org/details/wavetheoryofligh00crewrich, pp. 81–144. (Not to be confused with the earlier work of the same title in Annales de Chimie et de Physique, 1:238–81, 1816.)

- 1 2 3 Max Born and Emil Wolf, Principles of Optics, 1999, Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0-521-64222-4

- ↑ Huygens' Principle

- ↑ MV Klein & TE Furtak, Optics, 1986, John Wiley & Sons, New York

- ↑ Baggott, Jim (2011). The Quantum Story. Oxford Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-19-965597-7.

- ↑ Peter, Rodgers. "The double-slit experiment". www.physicsworld.com. Physics World. Retrieved 10 Sep 2018.

- 1 2 Alexander P. Veselov, "Huygens' principle and integrable systems", Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena 87 (1995) 9-13 DOI 10.1016/0167-2789(95)00166-2

- ↑ Alexander P. Veselov, "Huygens’ principle Archived 2016-02-21 at the Wayback Machine.", 2002

- ↑ "Wave Equation in Higher Dimensions" Stanford University, Math 220a class notes.

- ↑ M. Belger, R. Schimming and V. Wünsch, "A Survey on Huygens’ Principle", ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ANALYSIS UND IHRE ANWENDUNGEN Volume 16, Issue 1, 1997, pp. 9–36 DOI: 10.4171/ZAA/747

- ↑ Leifur Ásgeirsson, "Some hints on Huygens' principle and Hadamard's conjecture", Communications on Pure and Applied Mathematics, Volume 9, Issue 3, pages 307–326, August 1956

- ↑ Paul Günther, "Huygens’ principle and Hadamard’s conjecture", The Mathematical Intelligencer, March 1991, Volume 13, Issue 2, pp 56-63

- ↑ Yu. Yu. Berest, A. P. Veselov, "Hadamard's problem and Coxeter groups: New examples of Huygens' equations", Functional Analysis and Its Applications January 1994, Volume 28, Issue 1, pp 3-12

- ↑ Fabio A. C. C. Chalub and Jorge P. Zubelli, "Huygens’ Principle for Hyperbolic Operators and Integrable Hierarchies"

- ↑ Yuri Yu. Berest and Igor M. Loutsenko, "Huygens’ Principle in Minkowski Spaces and Soliton Solutions of the Korteweg-de Vries Equation", arXiv:solv-int/9704012 DOI 10.1007/s002200050235

Further reading

- Stratton, Julius Adams: Electromagnetic Theory, McGraw-Hill, 1941. (Reissued by Wiley – IEEE Press, ISBN 978-0-470-13153-4).