Horten Ho 229

| Ho 229 | |

|---|---|

| |

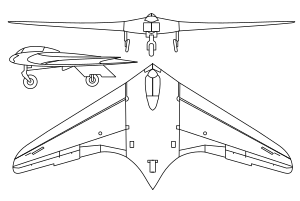

| H.IX V1 glider drawings | |

| Role | Fighter/Bomber |

| Manufacturer | Gothaer Waggonfabrik |

| Designer | Horten brothers |

| First flight | 1 March 1944 (glider) |

| Primary user | Luftwaffe |

| Number built | 3 |

The Horten H.IX, RLM designation Ho 229 (or Gotha Go 229 for extensive re-design work done by Gotha to prepare the aircraft for mass production) was a German prototype fighter/bomber initially designed by Reimar and Walter Horten to be built by Gothaer Waggonfabrik late in World War II. It was the first flying wing to be powered by jet engines.[1]

The design was a response to Hermann Göring's call for light bomber designs capable of meeting the "3×1000" requirement; namely to carry 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) of bombs a distance of 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) with a speed of 1,000 kilometres per hour (620 mph). Only jets could provide the speed, but these were extremely fuel-hungry, so considerable effort had to be made to meet the range requirement. Based on a flying wing, the Ho 229 lacked all extraneous control surfaces to lower drag. It was the only design to come even close to the 3×1000 requirements and received Göring's approval. Its ceiling was 15,000 metres (49,000 ft).[2]

Design and development

In the early 1930s, the Horten brothers had become interested in the flying wing design as a method of improving the performance of gliders. The German government was funding glider clubs at the time because production of military and even motorized aircraft was forbidden by the Treaty of Versailles after World War I. The flying wing layout removed the need for a tail and associated control surfaces and theoretically offered the lowest possible weight, using wings that were relatively short and sturdy, and without the added drag of the fuselage. The result was the Horten H.IV.[3]

In 1943, Reichsmarschall Göring issued a request for design proposals to produce a bomber that was capable of carrying a 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb) load over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) at 1,000 kilometres per hour (620 mph); the so-called "3×1000 project". Conventional German bombers could reach Allied command centers in Great Britain, but were suffering devastating losses from Allied fighters.[3] At the time, there was no way to meet these goals—the new Junkers Jumo 004B turbojets could provide the required speed, but had excessive fuel consumption.

The Hortens concluded that the low-drag flying wing design could meet all of the goals: by reducing the drag, cruise power could be lowered to the point where the range requirement could be met. They put forward their private project, the H.IX, as the basis for the bomber. The Government Air Ministry (Reichsluftfahrtministerium) approved the Horten proposal, but ordered the addition of two 30 mm cannons, as they felt the aircraft would also be useful as a fighter due to its estimated top speed being significantly higher than that of any Allied aircraft.

The H.IX was of mixed construction, with the center pod made from welded steel tubing and wing spars built from wood. The wings were made from two thin, carbon-impregnated plywood panels glued together with a charcoal and sawdust mixture. The wing had a single main spar, penetrated by the jet engine inlets, and a secondary spar used for attaching the elevons. It was designed with a 7g load factor and a 1.8× safety rating; therefore, the aircraft had a 12.6g ultimate load rating. The wing's chord/thickness ratio ranged from 15% at the root to 8% at the wingtips.[1] The aircraft utilized retractable tricycle landing gear, with the nosegear on the first two prototypes sourced from a He 177's tailwheel system, with the third prototype using an He 177A main gear wheelrim and tire on its custom-designed nosegear strutwork and wheel fork. A drogue parachute slowed the aircraft upon landing. The pilot sat on a primitive ejection seat. A special pressure suit was developed by Dräger. The aircraft was originally designed for the BMW 003 jet engine, but that engine was not quite ready, and the Junkers Jumo 004 engine was substituted.[1]

Control was achieved with elevons and spoilers. The control system included both long-span (inboard) and short-span (outboard) spoilers, with the smaller outboard spoilers activated first. This system gave a smoother and more graceful control of yaw than would a single-spoiler system.[1]

Given the difficulties in design and development, Russell Lee, the chair of the Aeronautics Department at the National Air and Space Museum, suggests an important purpose of the project for the Horton Brothers was to prevent them and their workers from being assigned to more dangerous roles by the German military.[4]

Operational history

Testing and evaluation

The first prototype H.IX V1, an unpowered glider with fixed tricycle landing gear, flew on 1 March 1944. Flight results were very favorable, but there was an accident when the pilot attempted to land without first retracting an instrument-carrying pole extending from the aircraft. The design was taken from the Horten brothers and given to Gothaer Waggonfabrik. The Gotha team made some changes: they added a simple ejection seat, dramatically changed the undercarriage to enable a higher gross weight, changed the jet engine inlets, and added ducting to air-cool the jet engine's outer casing to prevent damage to the wooden wing.[1]

The H.IX V1 was followed in December 1944 by the Junkers Jumo 004-powered second prototype H.IX V2; the BMW 003 engine was preferred, but unavailable. Göring believed in the design and ordered a production series of 40 aircraft from Gothaer Waggonfabrik with the RLM designation Ho 229, even though it had not yet taken to the air under jet power. The first flight of the H.IX V2 was made in Oranienburg on 2 February 1945.[3] All subsequent test flights and development were done by Gothaer Waggonfabrik. By this time, the Horten brothers were working on a turbojet-powered design for the Amerika Bomber contract competition and did not attend the first test flight. The test pilot was Leutnant Erwin Ziller. Two further test flights were made between 2 and 18 February 1945. Another test pilot used in the evaluation was Heinz Scheidhauer.

The H.IX V2 reportedly displayed very good handling qualities, with only moderate lateral instability (a typical deficiency of tailless aircraft). While the second flight was equally successful, the undercarriage was damaged by a heavy landing caused by Ziller deploying the brake parachute too early during his landing approach. There are reports that during one of these test flights, the H.IX V2 undertook a simulated "dog-fight" with a Messerschmitt Me 262, the first operational jet fighter, and that the H.IX V2 outperformed the Me 262.

Two weeks later, on 18 February 1945, disaster struck during the third test flight. Ziller took off without any problems to perform a series of flight tests. After about 45 minutes, at an altitude of around 800 m, one of the Jumo 004 turbojet engines developed a problem, caught fire and stopped. Ziller was seen to put the aircraft into a dive and pull up several times in an attempt to restart the engine and save the precious prototype.[5] Ziller undertook a series of four complete turns at 20° angle of bank. Ziller did not use his radio or eject from the aircraft. He may already have been unconscious as a result of the fumes from the burning engine. The aircraft crashed just outside the boundary of the airfield. Ziller was thrown from the aircraft on impact and died from his injuries two weeks later. The prototype aircraft was completely destroyed.[5][6]

Despite this setback, the project continued with sustained energy. On 12 March 1945, nearly a week after the U.S. Army had launched Operation Lumberjack to cross the Rhine River, the Ho 229 was included in the Jäger-Notprogramm (Emergency Fighter Program) for accelerated production of inexpensive "wonder weapons". The prototype workshop was moved to the Gothaer Waggonfabrik (Gotha) in Friedrichroda, western Thuringia. In the same month, work commenced on the third prototype, the Ho 229 V3.

The V3 was larger than previous prototypes, the shape being modified in various areas, and it was meant to be a template for the pre-production series Ho 229 A-0 day fighters, of which 20 machines had been ordered. The V3 was meant to be powered by two Jumo 004C engines, with 10% greater thrust each than the earlier Jumo 004B production engine used for the Me 262A and Ar 234B, and could carry two MK 108 30 mm cannons in the wing roots. Work had also started on the two-seat Ho 229 V4 and Ho 229 V5 night-fighter prototypes, the Ho 229 V6 armament test prototype, and the Ho 229 V7 two-seat trainer.

During the final stages of the war, the U.S. military initiated Operation Paperclip, an effort to capture advanced German weapons research, and keep it out of the hands of advancing Soviet troops. A Horten glider and the Ho 229 V3, which was undergoing final assembly, were transported by sea to the United States as part of Operation Seahorse for evaluation. On the way, the Ho 229 spent a brief time at RAE Farnborough in the UK,[3] during which it was considered whether British jet engines could be fitted, but the mountings were found to be incompatible[7] with the early British turbojets, which used larger-diameter centrifugal compressors as opposed to the slimmer axial-flow turbojets the Germans had developed. The Americans were just starting to create their own axial-compressor turbojets before the war's end, such as the Westinghouse J30, with a thrust level only approaching the BMW 003A's full output.

Surviving aircraft

The only surviving Ho 229 airframe, the V3—and the only surviving World War II-era German jet prototype still in existence—has been at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's Paul E. Garber Restoration Facility in Suitland, Maryland, U.S. In December 2011, the National Air and Space Museum moved the Ho 229 into the active restoration area of the Garber Restoration Facility, and it is being reviewed for full restoration and display.[8] The central section of the V3 prototype was meant to be moved to the Smithsonian NASM's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in late 2012 to commence a detailed examination of it before starting any serious conservation/restoration efforts[9] and has been cleared for the move to the Udvar-Hazy facility's restoration shops as of summer 2014, with only the NASM's B-26B Marauder Flak Bait medium bomber ahead of it for restoration,[10] within the Udvar-Hazy facility's Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar. As of early 2018, the surviving Horten Ho 229 is currently on display at the Udvar-Hazy Center.

Claimed stealth technology

After the war, Reimar Horten said he mixed charcoal dust in with the wood glue to absorb electromagnetic waves (radar), which he believed could shield the aircraft from detection by British early-warning ground-based radar that operated at 20 to 30 MHz (top end of the HF band), known as Chain Home.[11] A jet-powered flying wing design such as the Horten Ho 229 has a smaller radar cross-section than conventional contemporary twin-engine aircraft because the wings blended into the fuselage and there are no large propeller disks or vertical and horizontal tail surfaces to provide a typical identifiable radar signature.[12][5]

Engineers of the Northrop-Grumman Corporation had long been interested in the Ho 229, and several of them visited the Smithsonian Museum's facility in Silver Hill, Maryland in the early 1980s to study the V3 airframe, in the context of developing the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit. A team of engineers from Northrop-Grumman ran electromagnetic tests on the V3's multilayer wooden center-section nose cones. The cones are 19 mm (0.75 in) thick and made from thin sheets of veneer. The team concluded that there was some form of conducting element in the glue, as the radar signal attenuated considerably as it passed through the cone.[12] However, a later inspection by the museum found no trace of such material.

Northrop-built reproduction

In early 2008, Northrop Grumman paired up television documentary producer Michael Jorgensen and the National Geographic Channel to produce a documentary to determine whether the Ho 229 was, in fact, the world's first true "stealth" fighter-bomber.[12] Northrop Grumman built a full-size non-flying reproduction of the V3, constructed to match the aircraft's radar properties. After an expenditure of about US$250,000 and 2,500 man-hours, Northrop's Ho 229 reproduction was tested at the company's (RCS) test range at Tejon, California, where it was placed on a 15-meter (50 ft) articulating pole and exposed to electromagnetic energy sources from various angles, using the same three HF/VHF-boundary area frequencies in the 20–50 MHz range used by the Chain Home.[12]

RCS testing showed that a hypothetical Ho 229 approaching the English coast from France flying at 885 kilometres per hour (550 mph) at 15–30 metres (49–98 ft) above the water would have been visible to CH radar at a distance of 80% that of a Bf 109. This implies a frontal RCS of only 40% that of a Bf 109 at the Chain Home frequencies. The most visible parts of the aircraft were the jet inlets and the cockpit, but caused no return through smaller dimensions than the roughly ten-meter CH wavelength.

With testing complete, the reproduction was donated by Northrop Grumman to the San Diego Air and Space Museum.[12][13] The television documentary, Hitler's Stealth Fighter (2009), produced by Myth Merchant Films, featured the Northrop Grumman full-scale Ho 229 model as well as CGI reconstructions depicting a fictional wartime scenario, where Ho 229s were operational in both offensive and defensive roles, armed with "protruding" cannon barrels, an allusion to the proposed fitting of a pair of the existing, long-barreled (1.34 meters, 52-3/4 inch) MK 103 cannon proposed for the Ho 229.[14]

Expert Debunking of Stealth Claims

Due to the popularity of this documentary project, the Smithsonian has since posted an extensive debunking of these claims citing their own research and the paper published and presented at the 10th American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (ATIO) Conference held September 13 through 15 in 2010, in Fort Worth, Texas by the Northrop Grumman team followed in the Myth Merchant documentary.[15]

In his later life, Reimar Horten promoted the idea that the Horten Ho 229 V3 was intended to be built as a stealth aircraft, which would have placed this jet’s design several decades ahead of its time. Reimar Horten claimed that he wanted to add charcoal to the adhesive layers of the plywood skin of the production model to render it invisible to radar, because the charcoal “should diffuse radar beams, and make the aircraft invisible on radar” (Horten and Selinger 1983). This statement was published in his 1983 co-authored book Nurflügel (which translates as “Flying Wing”). While this statement refers to the never-made production model, it seems possible that the experimental charcoal addition could have been used on the Horten Ho 229 V3 prototype. The mere mention of early stealth technology sparked the imagination of aircraft enthusiasts across the world and spurred vibrant debate within the aviation community.

The stealth myth has been growing since the 1980s and was invigorated when the National Geographic Channel, in collaboration with Northrup Grumman, produced a documentary called "Hitler's Stealth Fighter" in 2009. The program featured the Horten Ho 229 V3 as a potential "Wonder Weapon" that arrived too late in the war to be used (Myth Merchant Films, 2009). The documentary also referred to the jet's storage location as "a secret government warehouse," which added to the mystique of this artifact. Since the airing of the documentary, public pressure has increased to remove the jet from its so-called secret government warehouse and put it on display. In fact, this secret warehouse is the Museum's Paul E. Garber Facility in Suitland, Maryland where a team of conservators, material scientists, a curator, and aircraft mechanic has been evaluating the aircraft.

The Smithsonian has performed a technical study of the materials used and determined that there is "no evidence of carbon black or charcoal in the Horten jet" thus invalidating the proposed mechanism for an essentially non-existent radar absorbent property as compared to the control sample of plywood used in the original testing.

"The Ho 229 leading edge has the same characteristics as the plywood [control sample] except that the frequency [do not exactly match] and have a shorter bandwidth. This indicates that the dielectric constant of the Ho 229 leading edge is higher than the plywood test sample. The similarity of the two tests indicates that the design using the carbon black type material produced a poor absorber."

Dobrenz and Spadoni use the term 'absorber' to refer to the ability of the Ho 229 leading edge to absorb the radar signal rather than reflecting it back to the antenna receiver. More absorption means less reflected signal and greater stealth. The authors assumed in their paper that crafts persons used the "carbon black material" to lower the RCS, however, our technical study findings described above found no evidence of carbon black or charcoal in the Horten jet.

Variants

- H.IX V1

- First prototype, an unpowered glider, one built and flown (three-view drawing above).[1]

- H.IX V2

- First powered prototype, one built and flown with twin Junkers Jumo 004B engines.[1]

Gotha Developments:

- Ho 229 V3

- Revised air intakes, engines moved forward to correct longitudinal imbalance. Its nearly completed airframe was captured in production, with two Junkers Jumo 004B jet engines installed in the airframe.

- Ho 229 V4

- Planned two-seat all-weather fighter, in construction at Friedrichroda, but not much more than the center-section's tubular framework completed.[1]

- Ho 229 V5

- Planned two-seat all-weather fighter, in construction at Friedrichroda, but not much more than the center-section's tubular framework completed.[1]

- Ho 229 V6

- Projected definitive single-seat fighter version with different cannon, mock-up in production at Ilmenau.

Horten Developments:

- H.IXb (also designated V6 and V7 by the Hortens)

- Projected two-seat trainer or night-fighter; not built.[1]

- Ho 229 A-0

- Projected expedited production version based on Ho 229 V6; not built.

Specifications (Horten Ho 229 V3)

From manufacturer's estimates—three-view drawing at top of page shows the H.IX V1 glider prototype.

Data from The Great Book of Fighters[16]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 7.47 m (24 ft 6 in)

- Wingspan: 16.76 m (55 ft 0 in)

- Height: 2.81 m (9 ft 2 in)

- Wing area: 50.20 m² (540.35 ft²)

- Empty weight: 4,600 kg (10,141 lb)

- Loaded weight: 6,912 kg (15,238 lb)

- Max. takeoff weight: 8,100 kg (17,857 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Junkers Jumo 004B turbojet, 8.7 kN (1,956 lbf) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 977 km/h (estimated) (607 mph) at 12,000 metres (39,000 ft)

- Service ceiling: 16,000 m (estimated) (52,000 ft)

- Rate of climb: 22 m/s (estimated) (4,330 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 137.7 kg/m² (28.2 lb/ft²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.26

Armament

- Guns: 2 × 30 mm MK 108 cannon

- Rockets: R4M rockets

- Bombs: 2 × 500 kilograms (1,100 lb) bombs.

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Green 1970, p. 247.

- ↑ Boyne 1994, p. 325.

- 1 2 3 4 Dowling, Stephen. "The Flying Wing Decades Ahead of its Time." BBC News, 2 February 2016.

- ↑ "Desperate for victory, the Nazis built an aircraft that was all wing. It didn't work". Smithsonian Insider. 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- 1 2 3 Handwerk, Brian (25 June 2009). "Hitler's Stealth Fighter Re-created". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ↑ "Horten Ho 229 V-2 (Ho IX V 2) der Absturz." Archived 2016-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. DeutscheLuftwaffe.de, Retrieved: 21 February 2016.

- ↑ Brown 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ "Horten Ho 229 V3 Technical Study and Conservation". hortenconservation.squarespace.com. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ↑ "National Air and Space Museum Image Detail – Horten H IX V3 Plan – Condition of the Major Metal Components". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on May 1, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Horten Flying Wing Heading to NASM's Udvar-Hazy Center". warbirdsnews.com. June 24, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Flying under the Radar: A History of Stealth Planes." National Geographic Channel, 2009. Retrieved: 6 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Myhra 2009, p. 11.

- ↑ "San Diego Air Museum will house replica German flying wing." signonsandiego.com. Retrieved: 6 July 2009.

- ↑ "Hitler's Stealth Fighter." Myth Merchant Films, 2009, first aired on 28 June 2009 on the National Geographic Channel (USA). Retrieved: 24 October 2010.

- ↑ "Is it Stealth?". Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ Green, William and Gordon Swanborough. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

Bibliography

- Boyne, Walter J. Clash of Wings. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994. ISBN 0-684-83915-6.

- Brown, Eric. Wings On My Sleeve: The World's Greatest Test Pilot tells his Story. London: Orion Books. 2006. ISBN 978-0-297-84565-2.

- Green, William. Warplanes of the Third Reich. London: Macdonald and Jane's Publishers Ltd., 1970. ISBN 0-356-02382-6.

- Myhra, David. The Horten Brothers and Their All-wing Aircraft. London: Bushwood Books, 1997. ISBN 0-7643-0441-0.

- Myhra, David. "Northrop Tests Hitler's 'Stealth' Fighter." Aviation History, Volume 19, Issue 6, July 2009.

- Shepelev, Andrei and Huib Ottens. Ho 229, The Spirit of Thuringia: The Horten All-wing jet Fighter. London: Classic Publications, 2007. ISBN 1-903223-66-0.

Further reading

- Thomas Dobrenz, Aldo Spadoni, Michael Jorgensen, "Aviation Archeology of the Horten 229 v3 Aircraft", 10th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations (ATIO) Conference

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Horten H.IX. |

- National Air & Space Museum's Ho 229 V3 Restoration Project Homepage

- Air & Space Smithsonian "Restoring Germany’s Captured 'Bat Wing'" Article on the Ho 229 V3's restoration, August 2016 issue

- Horten Nurflügels

- Arthur Bentley's scale drawings of the Ho-229

- Construction of a model of the Horten IX including CAD files (in German)

- "Horten: Two brothers, one wing"

- "Photo: Horten Ho 229 flying over Göttingen, Germany. 1945".

- The German Army Horten Ho-229