Homelessness in England

In England, local authorities have duties to homeless people under Part VII of the Housing Act 1996 as amended by the Homelessness Act 2002. There are five hurdles which a homeless person must overcome in order to qualify as statutory homeless. If an applicant only needs the first three of these tests Councils still have a duty to provide interim accommodation. However an applicant must satisfy all five for a Council to have to give an applicant "reasonable preference" on the social housing register.[1] Even if a person passes these fives tests councils have the ability to use the private rented sector to end their duty to a homeless person.[2]

The five tests are:

- Is the applicant homeless or threatened with homelessness?

- Is the applicant eligible for assistance?

- Is the applicant priority need?

- Is the applicant intentionally homeless?

- Does the applicant have a local connection?

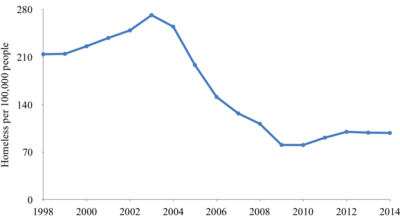

The annual number of homeless households in England peaked in 2003-04 at 135,420 before falling to a low of 40,020 in 2009-10. In 2014-15, there were 54,430 homeless households, which was 60 per cent below the 2003-04 peak.[3] However, in December 2016 the housing charity Shelter estimated homelessness in England to amount to more than 250,000 people; Shelter calculated the figure using four sets of official sources: statistics on rough sleepers, statistics on those in temporary accommodation, the number of people housed in hostels and the number of people waiting to be housed by council social services departments.[4]

In England, it had been estimated in 2007 an average of 498 people slept rough each night, with 248 of those in London.[5] But reportedly numbers sleeping rough have soared in recent years and doubled since 2010; figures reported for the 2015 count were 3,569 people rough sleeping in England on a single night, up 102% from 2010.[6]

Given the costs of providing temporary accommodation and the limited amount of social housing in the United Kingdom some Councils have been criticised for attempting to circumvent their duties under the law a process which has been termed "gatekeeping". The term "Non-statutory homelessness" covers people who are considered by the local authority to be not eligible for assistance, not in priority need or "intentionally homeless".[7][8]

Households in temporary accommodation rose from 35,850 in 2011 to 54,280 in early 2017. Part of the cause is people losing private tenancies, which Shelter maintains increased drastically since 2011 when housing benefit cuts began.[9] Almost three quarters of homeless people are single parent families. Just under 30,000 single parent families became homeless in 2017, this rose 8% from five years previously. Their limited income makes it hard for them to deal with rising living costs, high rents and benefit cuts. The number of households in temporary accommodation has risen by almost two thirds since 2010 and reached 78,930.[10]

Reasons for homelessness

In 2007/2008, the Office of the Deputy for Homelessness Statistics produced a table which showed some of the more immediate reasons for homelessness in England.[11] These were not underlying reasons but before the onset of homelessness. These reasons were given by the minister's report for 2007/2008 as:[12]

- 37% - Parents, family, or friends no longer willing or able to accommodate

- 20% - Loss of private dwelling, including tied accommodation

- 19% - Breakdown of relationship with partner

- 4% - Mortgage arrears

- 2% - Rent arrears

- 18% - other

The longer term causes of homelessness in England have been examined by a number of research studies. These suggest that both personal factors (e.g. addictions) and structural factors (e.g. poverty) are responsible for homelessness. A number of different pathways into homelessness have been identified.[13] There are additional factors that appear to be causes of homelessness among young people, most notably needing to face the responsibilities of independent living before they are ready for them [14]

The 2016 Homelessness Monitor report for England stated the bulk of the increase in statutory homelessness over the previous five years was attributable to sharply rising numbers of people made homeless from the private rented sector; as a proportion of all statutory homelessness acceptances loss of a private tenancy increased from 11 per cent in 2009-10 to 29 per cent in 2014-15 (from 4,600 to 16,000). This report concludes that 'homelessness worsened considerably' during the five years of the Coalition Government (2010–15) and adds 'services have been overwhelmed by the knock-on consequences of wider ministerial decisions, especially on welfare reform' (see Executive Summary).[15]

Government treatment of the homeless

Statutory Homeslessness Tests

All local authorities in England have a legal duty to provide 24-hour advice to homeless people, or those who are at risk of becoming homeless within 28 days.

A local authority must accept an application for assistance from a person seeking homelessness assistance if they have reason to believe that the person may be homeless or threatened with homelessness. They are then duty bound to make inquiries into that person's circumstances in order to decide whether a legal duty to provide accommodation and assistance is owed. "Interim accommodation" must be provided to those that may be eligible for permanent assistance pending a final decision. If the local authority decides that a person is homeless but does not fall into a priority need category, then a lesser duty shall be owed which does not extend to the provision of temporary accommodation. If the authority decides that a person is homeless and priority need but became homeless intentionally then the authority must secure that accommodation is available for such a period as will give the person reasonable time to find long term accommodation, which can extend to provision of temporary accommodation. The local authority shall in all the above cases be lawfully obliged to offer advice and assistance.

If the applicant qualifies under the five criteria (that they are not ineligible for housing, such as a person subject to immigration control; that the applicant is statutorily homeless or threatened with homelessness; that they are of 'priority need'; that the applicant is not intentionally homeless; and that the applicant has a local connection) then the local authority has a legal duty to provide accommodation for the applicant, those living with them, and any other person who it is reasonable to reside with them. However, if the applicant does not have a local connection with the district of the authority then they may be referred to another local authority with which they have a local connection (unless it is likely that the applicant would suffer violence or threats of violence in that other area).

Homelessness

A person does not have to be roofless to qualify legally as being homeless. They may be in possession of accommodation which is not reasonably tenable for a person to occupy by virtue of its affordability, condition, location, if it is not available to all members of the household, or because an occupant is at risk of violence or threats of violence which are likely to be carried out.

Eligibility

Certain categories of persons from abroad (including British citizens who have lived abroad for some time) may be ineligible for assistance under the legislation.

Priority need

People have a priority need for being provided with temporary housing (and a given a 'reasonable preference' for permanent accommodation on the Council's Housing Register) if any of the following apply:

- they are pregnant

- they have dependent children

- they are homeless because of an emergency such as a flood or a fire

- they are aged 16 or 17 (except certain care leavers [orphans, etc.] who remain the responsibility of social services)

- they are care leavers aged 18–20 (if looked after, accommodated or fostered while aged 16–17)

- they are vulnerable due to:

- old age

- a physical or mental illness

- a handicap or physical disability

- other special reason (such as a person at risk of exploitation)

- they are vulnerable as a result of

- having been in care (regardless of age)

- fleeing violence or threats of violence

- service in one of the armed forces

- having served a custodial sentence or having been remanded in custody.

Intentional homelessness

Under 191(1) and 196(1) of the Housing Act 1996, "a person becomes homeless intentionally or threatened with homelessness intentionally, if:

i) the person deliberately does or fails to do anything in consequence of which the person ceases to occupy accommodation (or the likely result of which is that the person will be forced to leave accommodation); ii) the accommodation is available for the person’s occupation; and iii) it would have been reasonable for the person to continue to occupy the accommodation.

However, an act or omission made in good faith by someone who was unaware of any relevant fact must not be treated as deliberate." [16]

Local connection

Someone may have a local connection with a local council area if they fulfil any of the following:

(1) they live in the area now or have done in the recent past, (2) they work in the area, or (3) they have close family in the area.

It is possible to have a local connection with more than one area.[17]

Rough sleeping

The official figures for England are that an average of 498 people sleep rough each night, with 248 of those in London (2007).[5] It is important to note that many individuals may spend only a few days or weeks sleeping rough, and so this number hides the total number of people actually affected in any one year. However, it is thought numbers sleeping rough have soared in recent years and doubled since 2010; figures reported for the 2015 count were 3,569 people rough sleeping in England on a single night, up 102% from 2010.[6]

Services for rough sleepers

A national service, called Streetlink, was established in 2012 to help members of the public obtain near-immediate assistance for specific rough sleepers, with the support of the Government (as housing is a devolved matter, the service currently only extends to England). Currently, the service does not operate on a statutory basis, and the involvement of local authorities is merely due to political pressure from the government and charities, with funding being provided by the government (and others) on an ad-hoc basis.

A member of the public who is concerned that someone is sleeping on the streets can report the individual's details via the Street Link website or by calling the referral line number on 0300 500 0914. Someone who finds themselves sleeping on the streets can also report their situation using the same methods. It is important to note that the Streetlink service is for those who are genuinely sleeping on the streets, and not those who may merely be begging, or ostensibly living their life on the streets despite a place to sleep elsewhere (such as a hostel or supported accommodation).

The service aims to respond within 24-hours, including an assessment of the individual circumstances and an offer of temporary accommodation for the following nights. The response typically includes a visit to the rough sleeper early in the morning that follows the day or night on which the report has been made. The service operates via a number of charities and with the assistance of local councils.

Where appropriate, rough sleepers will also be offered specialist support:

- if they have substance misuse issues, they will be referred for support from organisations such as St. Mungo's (despite the name, this is a non-religious charity)

- if they are foreign nationals with no right to access public funds in the UK, repatriation assistance will be offered, including finding accommodation in the home country, construction of support plans, and financial assistance.

The service was piloted in London, in 2010, under the title No Second Night Out, which has been gone on to become the brand name used for the service in a number of other council areas. Since the launch in 2010, a number of charities have provided the core functions of the service in London:

- Thames Reach runs the London Street Rescue Service which provides support to people sleeping on the streets of the capital,

- Broadway Outreach Teams provide services on the streets in the particular areas of Kensington and Chelsea, The City, and Heathrow Airport.

Recent trends

Localism Act

A provision of the Localism Act gave Councils greater discretion to place those who are statutory homeless in private sector accommodation. Critics have argued that this masks the level of homelessness by deterring people from applying in the first place.[18]

Critics have harshly critiqued the benefit cap and other welfare cuts, arguing that these policies lead to "social cleansing" and pointing to the displacement of families from inner London.[19]

Homelessness Prevention Programme

The Government at Westminster does recognise homelessness in England as a growing problem and announced a £40m initiative in Oct 2016 to help prevent people becoming homeless.[20] A network of Homelessness Prevention Trailblazer areas are to develop innovative approaches to prevent homelessness; early adopters are Greater Manchester, Newcastle and Southwark councils (HM Govt Homelessness Prevention Programme Oct 17th 2016).[21] Newcastle upon Tyne has successfully applied a cooperative and preventative approach to homelessness previous to 2016 by linking local government departments with other agencies and charities.[22]

Homelessness Reduction Act 2017

The Homelessness Reduction Act 2017 places a new duty on local authorities in England to assist people threatened with homelessness within 56 days and to assess, prevent and relieve homelessness for all eligible applicants including single homeless people from April 2018.[23] In short, no one should be turned away.

Homelessness advice

Practical advice regarding homelessness can be obtained through a number of major non-governmental organisations including,

- Citizens Advice Bureaus and some other charities also offer free legal advice in person, by telephone, or by email, from qualified lawyers and others operating on a pro bono basis

- Shelter provides extensive advice about homelessness and other housing problems on their website, and from the telephone number given there, including about rights and legal situations.

- In an emergency, a person contacts a local council.

See also

References

- ↑ http://england.shelter.org.uk/get_advice/social_housing/applying_for_social_housing/who_gets_priority

- ↑ http://www.insidehousing.co.uk/homeless-forced-into-private-rented-sector/6524606.article

- ↑ "Statutory Homelessness: April to June Quarter 2015" (PDF).

- ↑ Richardson, Hannah (1 December 2016). "More than 250,000 are homeless in England - Shelter" (BBC News From the section Education & Family). BBC News. Education and social affairs reporter. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- 1 2 "Homelessness Statistics September 2007 and Rough Sleeping – 10 Years on from the Target" September 2007 Department for Communities and Local Government: London

- 1 2 McVeigh, Tracy (4 December 2016). "Growing crisis on UK streets as rough sleeper numbers soar". The Observer. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ "About homelessness". Homeless Link. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ "The homeless people - a priority need?". Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ↑ One in 25 people homeless in England's worst hit areas BBC

- ↑ Almost 30,000 lone parent families made homeless in England in 2017 BBC

- ↑ Office of the Deputy Prime Minister for Homelessness Statistics, "Reasons for Homelessness in England", 2005/2006.

- ↑ "Housing needs, homelessness and lettings", UK Housing Review 2007/2008, University of York, England.

- ↑ Harding, Irving and Whowell,"Homelessness, Pathways to Exclusion and Opportunities for Intervention", 2011, The Cyrenians and Northumbria University School of Arts and Social Sciences Press.

- ↑ Harding, 2004, "Making it Work: the Keys to Success Among Young People Living Independently", 2004, Bristol: The Policy Press.

- ↑ "The homelessness monitor: England 2016 (pub Jan 2016)" (PDF). Crisis. Crisis and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ Communities and Local Government. gov.uk (PDF). The British Government https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7842/1304826.pdf. Retrieved 17 December 2017. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Shelter. england.shelter.org.uk http://england.shelter.org.uk/housing_advice/homelessness/rules/local_connection. Retrieved 17 December 2017. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ https://www.theguardian.com/housing-network/2015/feb/27/council-gatekeeping-scandal-homeless-exposed

- ↑

- Matthew Taylor, 'Vast social cleansing' pushes tens of thousands of families out of London, The Guardian (August 28, 2015).

- Jon Stone, Welfare cuts are leading to the 'social cleansing' of London, says Jeremy Corbyn, The Independent (July 21, 2015).

- 'Social cleansing' housing benefit cap row: Duncan Smith hits back, BBC News (April 24, 2012).

- ↑ "£40 million homelessness prevention programme announced 17 October 2016". Gov.UK press release. Department for Communities and Local Government, Prime Minister's Office, 10 Downing Street. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ "Homelessness Prevention Programme 17 October 2016". Gov.UK publications. Department for Communities and Local Government. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ "Homelessness in Newcastle". Newcastle Residential Areas. Kay's Geography. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ↑ "Homelessness Reduction Bill to become law". BBC News. 2017-03-23. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

Further reading

- Angell, Ian, "No More Leaning on Lamp-posts", London School of Economics

- BBC News, "Warning over homelessness figures: Government claims that homelessness numbers have fallen by a fifth since last year should be taken with a health warning, says housing charity Shelter", Monday, 13 June 2005.

- BBC News, "More than 250,000 are homeless in England - Shelter", December 1, 2016.

- BBC Radio 4, "No Home, a season of television and radio programmes that introduce the new homeless.", 2006

- "UK Housing Review", University of York, England

- The Guardian,"Homelessness section"

External links

- The Homelessness Code of Guidance for Local Authorities – Provides statutory guidance on Local Authority obligations towards homeless people

- Quarterly government statistics on statutory homelessness – Quarterly statistics from central government on statutory homelessness and rough sleeping statistics in England.

- Statutory Homelessness Statistics, England – since 2007

- StreetLink - Government funded homeless support service and charity

- Homeless link, "Facts and Figures"

- Homelessness Monitor "project reports" University research studies funded by the homeless people charity "Crisis".

- Shelter "databank" for England.