Ogier the Dane

Ogier the Dane (French: Ogier le Danois, Ogier de Danemarche; Danish: Holger Danske) is a legendary knight of Charlemagne who appears in many Old French chansons de geste. In particular, he features as the protagonist in La chevalerie Ogier (ca. 1220), which belongs to the Geste de Doon de Mayence ("cycle of the rebellious vassals").[1] The first part of this epic, the enfance[s] (childhood exploits) of Ogier, is marked by his duel against a Saracen from whom he obtains the sword Corte, followed by victory over another Saracen opponent from whom he wins the horse Broiefort. In subsequent parts, Ogier turns into a rebel with cause, seeking refuge with the King of Lombardy and warring with Charlemagne for many years, until he is eventually reconciled when a dire need for him emerges after another Saracen incursion.

His character is a composite based on a historical Autcharius Francus who was aligned with king Desiderius of Lombardy against Charlemagne. The legend of a certain Othgerius buried in Meaux is also incorporated into the Chevalerie. In Scandinavia he was first known as Oddgeir danski in the Old Norse prose translation Karlamagnús saga, but later became more widely known as Holger Danske and was given the pedigree of being Olaf son of King Gøtrik, in a Danish translation published in the 16th century. Holger Danske became a Danish folklore hero, with a sleeping hero motif attached to him.

Historical references

The Ogier character is generally believed to be based on Autcharius Francus (or Otkerus),[lower-alpha 1] a Frankish knight who had served Carloman and escorted his widow and young children to Desiderius, King of Lombardy, but eventually surrendered to Charlemagne.[2][lower-alpha 2] The Ogier character could also have been partly constructed from the historical Adalgis (or Algisus), son of Desiderius, who played a similar role.[lower-alpha 3][7][6] The chanson de geste does parallel this, and Ogier does seek refuge with the Lombardian king Didier or Désier (as Desiderius is styled in French).[8]

An unrelated Othgerius (Otgerius), a benefactor buried at the Abbey of Saint Faro in Meaux in France,[lower-alpha 4] became connected with Ogier by a work called Conversio Othgeri militis (ca. 1070–1080) written by the monks there.[2][9] This tradition is reflected in the chanson of Ogier, which states that the hero was buried at Meaux.[10]

There is no Ogier of consequence in Danish history; at least, no Ogier as such appears in Saxo Grammaticus's Gesta Danorum.[11] However, the Danish work Holger Danskes Krønike (1534) made Ogier into the son of King Gøtrek of Denmark[lower-alpha 5][12][11] (namely Olaf son of Gøtrek,[13] mentioned by Saxo). "Olgerus, dux Daniæ" ("Olger, War-Leader of the Danes") had rebuilt the St. Martin's monastery pillaged by the Saxons in 778, according to the chronicle of this monastery at Cologne (ca. 1050). However, this is not a contemporary record and may just be poetic fiction.[3][11]

Sword Cortain

Ogier the Dane had a sword named Cortain (also spelled Courtain, Cortana, Curtana, etc.) This name is the accusative case declension of Old French corte, meaning "short".[14]

The tradition that Ogier had a short sword is quite old. There is an entry for "Oggero spata curta" ("Ogier of the short sword") in the Nota Emilianense (ca. 1065–1075),[15] and this is taken as a nickname derived from his sword-name Cortain.[16] The sword name does not appear in the oldest extant copy of La chanson de Roland (Oxford manuscript), only in versions postdating the Nota.[17] According to the first part (enfances) of Chevalerie Ogier, the sword, which once belonged to Brumadant the Savage, was remade more than twenty times; finally it was tested on a block of marble and broke about a palm's length. It was reforged and named Corte or Cortain, meaning "short".[18] This became the weapon of a chivalric-minded Saracen named Karaheut,[lower-alpha 6] who gives it to Ogier so he can fight Brunamont in single combat.[19][20] The sword has appeared in chansons de geste somewhat predating Chevalerie Ogier, or composed around the same time as it, such as Aspremont (before 1190) and Renaut de Montauban (c. 1200).[21]

The Prose Tristan (1230–1235, expanded in 1240[22]) states that Ogier inherited the sword of the Arthurian knight Tristan, shortening it and thus naming it Cortaine.[lower-alpha 7][23][24] The English monarchy also laid claim to owning "Tristram's sword",[lower-alpha 8] and this according to Roger Sherman Loomis was the "Curtana" ("short") used in the coronation of the British monarch.[lower-alpha 9]

French sources

Ogier the Dane's first appearance (spelled Oger) in any work is in Chanson de Roland (c. 1060),[14] where he is not named as one of the douzepers (twelve peers or paladins) of Charlemagne, although he is usually one of the twelve peers in other works.[25] In the poeticized Battle of Ronceveaux, Ogier is assigned to be the vanguard and commands the Bavarian Army in the battle against Baligant in the later half.[26][20] He plays only a minor part in this poem, and it is unclear what becomes of him, but the Pseudo-Turpin knows of a tradition that Ogier was killed at Roncevaux.[27]

A full career of Ogier from youth to death is treated in La Chevalerie Ogier de Danemarche, a 13th-century assonanced poem of approximately 13,000 lines[lower-alpha 10] attributed to Raimbert de Paris. It relates Ogier's early years, his rebellion against Charles and eventual reconciliation.[1] This is now considered a retelling.[lower-alpha 11] Ogier in a lost original "Chevalerie Ogier primitive"[lower-alpha 12] is thought to have fought alongside the Lombards because Charlemagne attacked at the Pope's bidding, as historically happened in the Siege of Pavia (773–74),[28] that is, there was no fighting with the Saracens as a prelude to this.

The legend that Ogier fought valiantly with some Saracens in his youth is the chief material of the first branch (about 3,000 lines[lower-alpha 13]) of Raimbert's Chevalerie Ogier.[31] This is also recounted in Enfances Ogier (c. 1270), a rhymed poem of 9,229 lines by Adenet le Roi. The story of Ogier's youth develops with close similarity in these two works starting at the beginning, but they diverge at a certain point when Raimbert's version begins to be more economical with the details.[32]

Ogier in versions of the Renaissance travels to the Avalon ruled by King Arthur and eventually becomes Morgan le Fay's paramour. This is how the story culminates in Roman d'Ogier, a reworking in Alexandrines written in the 14th century, as well as its prose redaction retitled Ogier le Danois (Ogyer le Danois) printed in a number of editions from the late 15th century onwards.[33][lower-alpha 14]

There are also several texts that might be classed as "histories" which refer to Ogier. Girart d'Amiens' Charlemagne contains a variant of Ogier's enfances.[34][35] Jean d'Outremeuse's Ly Myreur des Histors writes of Ogier's combat with the capalus (chapalu). Philippe Mouskes's 13th-century Chronique rimée writes on Ogier's death.[36]

Chevalerie Ogier

Ogier is the main character in the poem La Chevalerie Ogier de Danemarche (written ca. 1200–1215). Here he is the son of Geoffroy de Danemarche given as a hostage to Charlemagne. Ogier's son is slain by Charlot, son of Charlemagne. Ogier attacks Charlot and demands his life in revenge, resulting in his banishment. Ogier wars with Charlemagne for seven years and survives prison for another seven years. They eventually make peace and Ogier goes to fight at Charlemagne's side against the Saracens, in which battle he slays the giant Brehus. The work consists of twelve parts (or "branches") of varying lengths.[lower-alpha 15][37]

Ogier, a condemned hostage, is initially an unarmed spectator when Charles fights Saracens in Italy at the Pope's request. But when the French suffer a setback, Ogier joins the fight, seizing a flag and arms from a fleeing standard-bearer, and is knighted by the king in gratitude.[38] Next, Ogier accepts the challenge of single combat from the Saracen Karaheut,[lower-alpha 6] but enemies interrupt and abduct Ogier. Karaheut protests for Ogier's release, to no avail, and loses his engagement to the admiral's daughter.[39] She now wishes to marry the newcomer on the battlefield, Brunamont of Maiolgre (Majorca), but her wish will only be granted if a champion fights against Brunamont, and she names Ogier. Ogier, armed with Karaheut's sword Cortain, vanquishes Brunamont and wins the horse Broiefort.[40][21]

Roman d'Ogier

The 14th-century Roman d'Ogier is a refacimento in Alexandrines[lower-alpha 16][42] of 29,000 verses.[43][lower-alpha 17] In this version, Ogier is fated to be taken away by Morgan le Fay to Avalon and become her paramour. This fate is set in motion while Ogier is still a newborn in his crib. Six fées visit the baby, each with a gift, and Morgan's gift is longevity and life living with her. Ogier has an enhanced career, even becoming King of England,[lower-alpha 18] and when he reaches the age of 100, he is shipwrecked by Morgan so he can be conveyed to Avalon. He returns after two hundred years to save France, and is given a firebrand which must not be allowed to be burnt down for him to remain alive.[lower-alpha 19] Ogier tries to forfeit his life after accomplishing his task but is save by Morgan.[44][45] It states the Ogier and Morgan have a son named Meurvin, who himself became the subject of a lengthy Renaissance era romance.[46]

Legend at Meaux

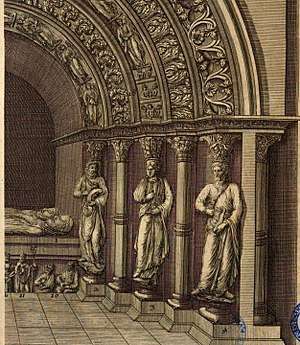

View entire right half / view entire illustration (from 1735 edition).

A legend of Conversio Othgeri militis was invented by the monks at the abbey of Saint Faro at Meaux around 1070–1080. It claimed Othgerius Francus ("Frankish") to be the most illustrious member of Charlemagne's court after the king himself,[47] thus making him identifiable with Ogier the Dane.[lower-alpha 20] He was buried in the abbey in a mausoleum built for him. His remains were placed in a sarcophagus lidded with his recumbent tomb effigy lying next to that of Saint Benedictus, and the chamber was enshrined with erect statues of various figures from the Charlemagne Cycle.[2][9][20]

This document was first commented on by Jean Mabillon in his Acta Sanctorum Ordinis S. Benedicti,[47] printed editions of which include a detailed illustration of the mausoleum at St. Faro. The statues at the mausoleum even included la belle Aude, affianced to Roland,[9] with one of the inscriptions there (according to Mabillon) claiming that Aude was Ogier's sister.[49][50][lower-alpha 21] It underwent restoration in 1535 by the Italian Gabriele Simeoni.[lower-alpha 22][51][52] That mausoleum is no longer preserved, but an illustration of the interior was printed in editions of Mabillon's Acta Sanctorum Ordinis S. Benedicti.[53][54]

-Pl_XI-tete-meaux.jpg)

A stone head later found in Meaux was determined to be Ogier's head from comparisons with these incunabula etchings.[55] This stone head can still be viewed today.

Scandinavia

The early form of the chanson de geste was translated in the 13th century into Old Norse as Oddgeirs þáttr danska ("Story of Oddgeir danski"), Branch III of the Karlamagnús saga. An Old Danish version of it, Karl Magnus krønike, was later created (some copies date to 1480).[56]

The 16th-century Olger Danskes krønike was a Danish translation of the French prose romance Ogier le Danois by Kristiern Pedersen, started while in Paris in 1514–1515, probably completed during his second sojourn in 1527, and printed in 1534 in Malmö.[12][11] Pedersen also fused the romance with Danish genealogy, thus making Ogier the son of Danish king Gøtrik (Godfred).[57][11]

Balladry

"Holger Danske og Burmand" (DgF 30, TSB E 133) recounts the fight between the hero and Burmand, described as a giant (and not a Saracen).[56] The ballad also exists in Swedish (SMB 216) and tells the story of how Holger Dansk is released from prison to fight against a troll by the name of Burman.[58][59]

Kronborg legend

Similar to Frederick Barbarossa, Saint Wenceslas and King Arthur, Ogier in Danish legend becomes a king in the mountain; he is said to dwell in the castle of Kronborg, his beard grown down to the floor. He will sleep there until some day when the country of Denmark is in peril, at which time he will rise up and save the nation. This is a common folklore motif, classed as Type 1960.2, "The King Asleep in the Mountain".[60] According to the tour guides of Kronborg Castle, legend has it that Holger sat down in his present location after walking all the way from his complete battles in France.

The 1789 opera Holger Danske, composed by F.L.Æ. Kunzen with a libretto by Jens Baggesen, had a considerable impact on Danish nationalism in the late 18th century. It spawned the literary "Holger feud", which revealed the increasing dissatisfaction among the native Danish population with the German influence on Danish society. The Danish intellectual Peter Andreas Heiberg joined the feud by writing a satirical version entitled Holger Tyske ("Holger the German") ridiculing Baggesen's lyrics. During the German occupation of Denmark, presentation of the same opera in Copenhagen became a manifestation of Danish national feeling and opposition to the occupation.

In art

The hero's popularity led to him being depicted on 15th- and 16th-century paintings in two churches in Denmark and Sweden.[11] The Holger Danske and Burman painted on the ceiling of Floda Church in Sweden are attributed to Albertus Pictor around 1480. It also includes the text Holger Dane won victory over Burman; this is the burden of the Danish and Swedish ballad, but the painting predates other written texts for this ballad.[61][62]

The Hotel Marienlyst in Helsingør commissioned a statue of Holger Danske in 1907 from the sculptor Hans Peder Pedersen-Dan. The bronze statue was outside the hotel until 2013, when it was sold and moved to Skjern.[63][64] The bronze statue was based on an original in plaster. The plaster statue was placed in the vaults at Kronborg castle, also in Helsingør, where it became a popular attraction in its own right.[65] The plaster statue was replaced by a concrete copy in 1985.[66]

Eponyms

- The largest World War II Danish resistance group, Holger Danske, was named after the legend.

- On the slopes of Rönneberga outside Landskrona in south Sweden (formerly a part of Denmark), there is a burial mound named Holger Danske mound.

Popular culture

- In Rudyard Kipling's poem "The Land" (1916), "Ogier the Dane" is the archetypal name used to signify Danish invaders who have overran Sussex over the years.

- In Poul Anderson's fantasy novel Three Hearts and Three Lions (1961), Danish Resistance member Holger Carlsen time warps and learns that he is Ogier the Dane.

- In Per Petterson's I Curse the River of Time (2001), there is a ferry named Holger Danske.[lower-alpha 23]

Explanatory notes

- ↑ "Autcharius" is the spelling as occurs in the Vita Hadriani (biography of Pope Adrian I in the Liber Pontificalis, "Otkerus" in a work by a monk of St. Gall (fl. 885).[2][3]

- ↑ Knud Togeby objected to identifying with Autcharius, and proposed Audacar who led Charlemagne's troops in Bavaria.[4][5]

- ↑ The exploits of "Algisus" is given full account in the Chronicon novaliciense.[6]

- ↑ Bédier's characterization was that this Othgerius had no distinction besides having donated some parcels of land to the abbey and being buried there (Voretzsch (1931), p. 209).

- ↑ "Gøtrek" is the spelling in Hanssen (1842) edition of the text. But there are various spellings: "Godfred",[11] etc.

- 1 2 "Karaheut" in Ludlow (1865) and Voretzsch (1931), p. 209; The courtois "Karaheu" in Togeby (1969), p. 51. Langlois, table des noms, p. 132, lists "Caraheu, Craheut, Karaheu, Karaheut, Karaheult, Kareeu". "Karahues" and "Karahuel" are also used.

- ↑ This passage is not included in Curtis (1994)'s English translation.

- ↑ King Johan received "duos enses scilicet ensem Tristrami.. (two swords, namely Tristram's sword.. )", Patent Rolls for 1207.

- ↑ Loomis also argues that Curtana's origins as Tristram's sword was known to the author of this passage in Prose Tristan, but the tradition was forgotten in England.

- ↑ More than 13,000 in the Barrois edition, less in Eusebi's edition.

- ↑ Bédier called it a "remaniement (reworking)",[28] but this term is also used by Keller to refer to the Alexandrine version.

- ↑ Bédier's term

- ↑ 3102 lines in Barrois's edition.[29][30]

- ↑ The Alexandrines version may contain some vestiges of the lost 12th century Chevalerie Ogier.[1]

- ↑ Barrois edited the text divided into theses branches, and made the determinations on where the divisions by the dropped capital letters in one of the manuscripts (ms. B). (Togeby (1969), p. 46).

- ↑ "refacimento" was the term employed by Pio Rajna[41] as well as by Paton. But this means "reworking", and the term has been indiscriminately applied to other works, not necessarily the Alexandrine version.

- ↑ For a list of excerpts and summary, see Paton (1903), p. 75 notes 2 and 7.

- ↑ He does rescue and marry the daughter of the king of England in the older version.

- ↑ Ward notes the firebrand is a motif seen in the legend of Meleager.

- ↑ Various references cite this document ("Conversion of Othger") as being one (purportedly) about Ogier.[1] Cerf even refers to the document as Conversio Ogeri militis ("Conversion of Ogier").[48]

- ↑ Togeby (1966), p. 113 states it differently, that the inscriptions agree with the chanson Girart de Vienne where Aude is Oliver's sister. But Mabillon can be quoted thus: "..forsan ab Auda matre, Otgerii nostri sorore, Rotlando nupta".

- ↑ This is pointed out by {Philipp August Becker, state by Mabillon.

- ↑ Translated into English by Charlotte Barslund from the Norwegian. The ferry sails between Norway and Denmark.

References

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Keller, Hans-Erich (1995). Kibler, William; Zinn, Grover A., eds. Chevaleri Ogier. Medieval France: An Encyclopedia. Garland. pp. 405–406. ISBN 978-0-8240-4444-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Voretzsch (1931), p. 209.

- 1 2 Dunlop & Wilson (1906), Wilson's note 1 (p. 330)

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 19.

- ↑ Emden (1988), p. 125.

- 1 2 Ludlow (1865), pp. 274ff, note.

- ↑ Voretzsch (1931), p. 208.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 265–273.

- 1 2 3 Shepard, W. P. (1921). Chansons de Geste and the Homeric Problem. The American Journal of Philology. 42. pp. 217–218. JSTOR 289581

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), p. 301.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Holger Danske", Nordisk familjebok, 1909 (in Swedish)

- 1 2 Jensen, Janus Møller (2007), Denmark and the Crusades, 1400–1650, BRILL, ISBN 9789047419846

- ↑ Hanssen (1842), p. 4: "Saa lod han ham christne og kaldte ham Oluf; men jeg vil kalde ham Olger (Then he was Baptized and christened Oluf, but I shall call him Ogier)".

- 1 2 Togeby (1969), p. 17.

- ↑ Sholod, Barton (1966). Charlemagne in Spain: The Cultural Legacy of Roncesvalles. Librairie Droz. p. 189.

- ↑ Togeby (1966), p. 112.

- ↑ Togeby (1966), p. 112 and Togeby (1969), p. 17

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), p. 256.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), p. 260.

- 1 2 3 van Dijk, Hans (2000). Gerritsen, Willem Pieter; Van Melle, Anthony G., eds. Ogier the Dane. A Dictionary of Medieval Heroes. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 186–188. ISBN 978-0-85115-780-1.

- 1 2 Togeby (1969), p. 52.

- ↑ Curtis, Renée L. (trans.), ed. (1994), The Romance of Tristan, Oxford, p. xvi ISBN 0-19-282792-8.

- ↑ Löseth, Eilert (1890), Analyse critique du Roman de Tristan en prose française, Paris: Bouillon, p. 302 (in French)

- ↑ Loomis, Roger Sherman (1922), "Tristram and the House of Anjou", The Modern Language Review, 17 (1): 29

- ↑ Cresswell, Julia (2014), Charlemagne and the Paladins, Bloomsbury Publishing, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Baker, Julie A. (2002), The Childhood of the Epic Hero: A Study of the Old French Enfances Texts of Epic Cycles, Indiana University, p. 54

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 28.

- 1 2 Bédier (1908), 2, pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Barrois (1842), I, p. lxxv.

- ↑ Henry (ed.) & Adenet (1956), p. 21.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 249–261.

- ↑ Henry (ed.) & Adenet (1956), pp. 21, 24–25.

- ↑ Taylor, Jane H. M. (2014). Rewriting Arthurian Romance in Renaissance France: From Manuscript to Printed Book. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Granzow (ed.) & Girart d'Amiens (1908), Charlemagne

- ↑ Baker (2002), p. 64.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 112.

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 46.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 249–252.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 252–259.

- ↑ Ludlow (1865), pp. 259–261.

- ↑ Rajna, Pio (1873), "Uggeri il Danese nella letteratura romanzesca degi Italiani", Romania, 2: 156, note 1 (in French)

- ↑ Paton (1903), p. 74.

- ↑ Reiss, Edmund; Reiss, Louise Horner; Taylor, Beverly, eds. (1984). Arthurian Legend and Literature: The Middle Ages. 1. Garland. p. 402. ISBN 9780824091231.

- ↑ Ward (1883), I, pp. 607–609.

- ↑ Child, Francis James (1884), "37. Thomas Rymer", The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Houghton Mifflin, I, p. 319

- ↑ Paton (1903), p. 77.

- 1 2 Cerf (1910), p. 2.

- ↑ Cerf (1910).

- ↑ Togeby (1969), p. 145.

- ↑ d'Achery & Mabillon (1677), p. 661n.

- ↑ Becker, Philipp August (1942), "Ogier Von Dänemark", Zeitschrift für französische Sprache und Literatur, 64 (1): 75, note 4 JSTOR 40615765 (in German)

- ↑ d'Achery & Mabillon (1677), p. 664.

- ↑ d'Achery, Lucas; Mabillon, Jean (1677), Acta Sanctorum Ordinis S. Benedicti: Pars Prima, IV, apud Ludovicum Billaine, in Palatio Regio, p. 664 (in Latin)

- ↑ Mabillon, Jean (1735), Acta Sanctorum Ordinis S. Benedicti: Pars Prima, IV, Coletus & Bettinellus, p. 624 (in Latin)

- ↑ Gassies, Georges (1905), "Note sur une tête de statue touvée à Meaux", Bulletin archéologique du Comité des travaux historiques et scientifiques: 40–42

- 1 2 Layher (2004), p. 93.

- ↑ Hanssen (1842), p. 1.

- ↑ Layher (2004), p. 98.

- ↑ The Faraway North, Scandinavian Folk Ballads, I. Cumpstey, 2016 ( ISBN 978-0-9576120-2-0)

- ↑ Baughman, Ernest W. (1966), Type and Motif-Index of the Folktales of England and North America, Walter de Gruyter, p. 122

- ↑ Malmberg, Christer. "Albertus Pictor - Floda kyrka". christermalmberg.se.

- ↑ Layher (2004), pp. 90–92.

- ↑ "Nu sover Holger Danske i Skjern".

- ↑ http://nyheder.tv2.dk/article.php/id-67626386%3Aholger-danske-ryger-til-skjern-solgt-for-rekordbel%C3%83%C2%83%C3%82%C2%83%C3%83%C2%82%C3%82%C2%B8b.html

- ↑ "Holger Danske - Udforsk slottet - Kronborg Slot - Slotte og haver - Kongelige Slotte". kongeligeslotte.dk.

- ↑ "Holger Danske - Ogier the Dane".

- Bibliography

- (primary sources)

- Raimbert de Paris (1842). Barrois, Joseph, ed. La chevalerie Ogier de Danemarche. Paris: Techener. Tome 1, Tome 2.

- Hanssen, Nis, ed. (1842), Olger Danskes Krønike, C. Molbech, Louis Klein, pp. 74–77

- Adenet le Roi (1996) [1956]. Henry, Albert, ed. Les enfances Ogier. Paris: Slatkine.

- Girart d'Amiens (1908), Granzow, Willi, ed., Die Ogier-Episode im "Charlemagne" des Girart d'Amiens, Hans Adler

- (secondary sources)

- Bédier, Joseph (1908), Les légendes épiques: recherches sur la formation des chansons de geste, 2 (1st ed.), pp. 184–185, 281–318 ; 3rd ed., pp. 191–194, 291-337

- Cerf, Barry (1910), "Ogier le Danois and the Abbey of St. Faro of Meaux", Romantic Review, 1 (1): 1–12

- Emden, W.G. van (1988), "The New Ogier Corpus", Mediaeval Scandinavia, 12

- Dunlop, John Colin (1906). Wilson, Henry, ed. Ogier le Danois. History of Prose Fiction. 1. G. Bell and sons. pp. 329–338.

- Ludlow, John Malcolm Forbes (1865), Popular epics of the middle ages of the Norse-German and Carlovingian Cycles, 2, London: Macmillan, pp. 247-

- Layher, William (2004), Bennett, P.E.; Green, R. Firth, eds., "Looking up at Holger Dansk og Burmand DgF 30", The Singer and the Scribe: European Ballad Traditions and European Ballad Cultures, Rodopi, pp. 89–104, ISBN 978-9-0420185-1-8

- Paton, Lucy Allen (1903), Studies in the Fairy Mythology of Arthurian Romance, Ginn&Company, pp. 74–77

- Togeby, Knud (1969), Ogier le Danois dans les littérratures européennes, Munksgaard

- Togeby, Knud (1966), "Ogier le Danois", Revue Romane, 1: 111–119

- Voretzsch, Karl (1976) [1931]. Introduction to the Study of Old French Literature. Genève: Slatkine. pp. 208–210.

- Ward, Harry Leigh Douglas (1883), Catalogue of romances in the Department of manuscripts in the British Museum, I, London: William Clowes, pp. 604-

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holger Danske. |