History of the central steppe

Sea

Darya

Balkash

garia

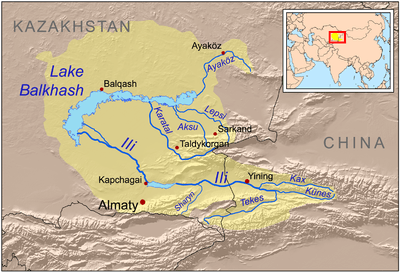

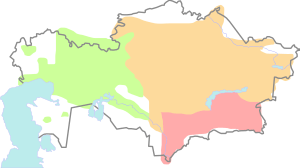

Note the east-west Kyrgyz mountains

This is a short History of the central steppe, an area roughly equivalent to modern Kazakhstan. Because the history is complex it is mainly an outline and index to the more detailed articles given in the links. It is a companion to History of the western steppe and History of the eastern steppe and is parallel to the History of Kazakhstan and the History of central Asia.

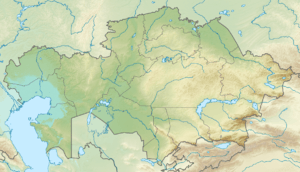

Geography

"Central steppe" is an informal term for the middle part of the Eurasian steppe. It is grassland with some semi-desert and becomes dryer toward the south. On the east it is separated from Dzungaria and the eastern steppe by the low mountains along the current Chinese border. On the west it merges into the western steppe along the narrowing between the Ural Mountains and the Caspian Sea. On the north it is bounded by the forests of Siberia. The southern boundary has three sections. In the east the Tian Shan mountains of Kyrgyzstan extend about 650 kilometres west and give the steppe a sharp southern boundary. The center is approximately the line of the Syr Darya which runs from the eastern mountains northwest to the Aral Sea. South of the Syr Darya the steppe grades into semi-desert but there are cities based on irrigation agriculture which give the area a different history. The western part between the Aral and Caspian Seas is dry and thinly populated. The Syr Darya and the area between the Urals and Caspian were not significant barriers and the low mountains of Dzungaria were fairly easy to cross. The other boundaries were significant barriers to movement.

General

The central steppe is far from the areas of literate civilization and is therefore poorly documented. Most of the "peoples" mentioned were some tribe or clan that gained power over its neighbors and became important enough to be noticed by literate historians. Some were definite ethnic groups and some movements were genuine folk migrations, but in most cases we do not know. Most dates are circa because they were processes or ill-documented. There are two major facts which theorists have not explained. During the last 2,500 years nearly all movements on the steppe have been from east to west. From about 1000 BC all the known peoples of the western and central steppe spoke Iranian languages. From about 500 AD the Turkic languages expanded from Mongolia and replaced most of the Iranian languages.

Before written history

Omits Yamnaya culture northwest of the Caspian.

The origins of pastoral nomadism and horse archery are not clearly understood. At some time in the distant past people of European appearance lived in or crossed the central steppe and left the Tarim mummies in the Tarim basin. In the centuries around 3000 BC we find the semi-nomadic and probably Indo-European Yamnaya culture west of the central steppe. East of the central steppe was the rather similar Afanasevo culture. The Yamnaya-Afanasevo complex is probably connected to the eastward spread of the Indo-European languages, especially Tokharian. Between them on the central steppe was the horse-using Botai culture. After 2000 BC the Andronovo Culture complex was southeast of the Urals. They had chariots, fortified towns, spread southeast to much of central Asia and are associated with the rise of the Indo-Iranian languages. Iron appears about 1000 BC. Around 500 BC Herodotus vaguely described the area as inhabited by Massagetae, Issidonians and others. Around 200 BC we begin to get Chinese reports from the east.

Eastern third (Zhetysu or Semirechye)

The area north of the Tien Shan needs special treatment because of the better documentation and the large number of peoples who moved thru it. It is a kind of steppe "bay" bounded on the north by the Siberian forests, on the south by the Kyrgyz mountains and on the east by low mountains. Zhetysu is Turkic and Semirechye is Russian for "seven rivers".

- Sakas (before 200 BC) The Iranian-speaking nomads in the western and central steppe were called Scythians by the Greeks, Sakas by the Persians and Sai by the Chinese, the three words meaning about the same thing. They also occupied the western Tarim basin. Iranian languages extended south to Persia and Afghanistan.

- Chinese: Under the Han dynasty the Chinese expanded to the west. In 125 BC Zhang Qian returned with the first reports of the Western Regions. Around 100 BC to 100 AD, with interruptions, the Chinese controlled the Tarim Basin southeast of the central steppe. Chinese historians give us the first good information about the central steppe.

- c. 162-132 BC: Yuezhi: The Yuezhi were originally a major power in Gansu and Mongolia. Around 162 BC they were driven west by the Xiongnu and settled in the Ili valley, driving out the Sakas. About 132 BC they were driven out by the Wusun and moved south and later formed a major state in Bactria as the Kushans.

- Wusun: c. 133 BC-100 AD: The Wusun from Gansu drove the Yuezhi out of the Ili valley. By c. 80 BC they had some power in the Tarim basin. After 100 AD they declined and gradually disappear from the records.

- Xiongnu (c. 40 BC-c. 155 AD): When the Northern Xiongnu were driven west by the Chinese they occupied Dzungaria and Semirechye, perhaps somewhat north of the Wusun. The Xianbei who defeated them may also reached this area.

- Yueban : (c. 160-490): After the Han lost control of the Tarim basin our sources become thin. The Chinese called the local population Yueban or Yuepan. They appear to have been Xiongnu remnants.

- ?Ephthalites (c. 493?-c. 560): The poorly-documented Ephthalites were based in the south and may have extended north of the Tian Shan.

- Tiele people (c. 100-800) is a vague Chinese term for the probably Turkic peoples mainly on the northern edge of the steppe from Mongolia westward.

- Outside influences (c. 500-800): Turkic-speaking peoples spread from Mongolia and occupied the central steppe. The Chinese returned under the Tang dynasty. Islam arrived about 750. Meanwhile, the Sogdian merchants controlled most of the long-distance trade.

- Gokturks (c. 558-657): The Gokturks were the first Turkic-speakers to found an empire and were the first to rule both the eastern and central steppe, the only other case being the Mongols. In 552 they took over Mongolia, c. 558 reached the Volga and c. 571 reached the Oxus. By 603 the Western Turkic Khaganate had definitely split from the Eastern Khaganate in Mongolia. Circa 657 they were defeated by the Chinese.

- Chinese again (c. 657-756): Chinese power was restored by the Tang dynasty. They took over the Tarim basin and the mountains of Kyrgyzstan, captured Tashkent, subjugated what was left of the western Turks and lost a battle to the Arabs in 751. Around 756 they withdrew because of the An Lushan rebellion.

- Islam (c. 750–present): After the Arab conquest of Merv in 651 there were raids northward. From 705 Islam expanded into the area between the Oxus and Syr Darya. Muslims in central Asia soon became more Persian than Arab. From around 750 Islam expanded slowly north of the Syr Darya and into the Tarim Basin and Gansu.

- Sogdian Merchants (c. 300-840): Merchants from Sogdia controlled most of the trade between China and the west. They had settlements all the way from Bukhara to northern China.

- Dulu Turks (c. 603-659): were the semi-independent eastern half of the Western Turkic Khaganate.

- Chinese vassals (c. 658-756): After the defeat of the Gokturks the Chinese had some limited control of the peoples west and north of the mountains, but the matter is poorly documented.

- Turgesh (c. 699-766): The Turgesh were Dulu who restored a kind of Turkic Khaganate. Fought Arabs and Chinese.

- Karluks (c. 766-840): The Turkic Karluks drove the Turgesh out of Semirechye and later evolved into the Karakhanids. As a tribe they originated in Dzungaria and existed from at least 644 into Mongol times.

- Karakhanids (c. 850-1134): The Karakhanid Khaganate was founded by Karluks and others. c. 960 they adopted Islam. c. 999 they conquered Transoxiana. About 1041 they split into an eastern group in Semirechye and a western group in Transoxiana. By 1081 they were Seljuk vassals, at least in theory. Following their defeat in 1134, many Karakhanids remained as local rulers.

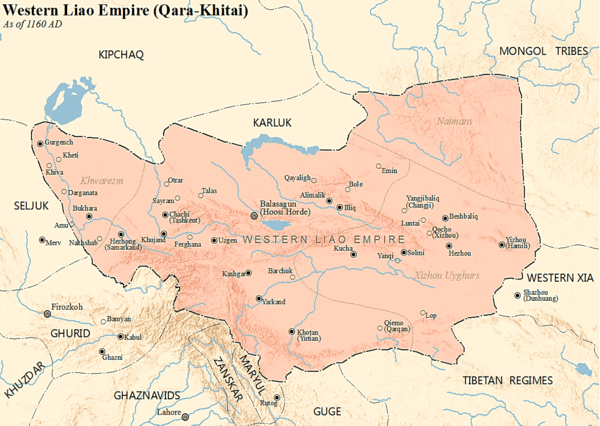

- Karakitai (1134–1220): The Karakitai rulers were refugees from north China. The Manchurian Kitans ruled north China as the Liao dynasty (907–1125). After they were overthrown by the Jurchens, Kitan remnants fled west, conquered Semirechye in 1134 and by 1141 held most of the lands of the Karakhanids. They were non-Muslim, had some degree of Chinese culture and generally left the former rulers in place as vassals. In 1211 a Naiman prince who had fled the Mongols usurped power. The Mongols pursued him and by 1220 conquered most of the Karakitai lands.

- Mongols and after: After the Mongol conquest in 1220 the eastern third does not need separate treatment, so see the "Mongols and after" section below. Continuing with Zhetysu we might mention the following.

- Chagataids: When the Mongol empire split up central Asia fell to the Chagataids but they never formed a strong state and soon adopted Islam and the local language.

- Moghulistan (c. 1450-1500): emerged from declining Chagataids. Zhetysu was split between Mogulistan in the east and the emerging Kazakhs.

- Kazakhs (1465–present) first appeared in Zhetysu and soon spread their name all over the central steppe. Semirechye was under the Senior Horde.

- Dzungar Khanate (c. 1680-1758) held the area until it was destroyed by the Chinese.

- Russians conquered the area from the north in 1847–68. See Russian conquest of Turkestan.

Westerm two-thirds and Turkic migrations

This area is far from areas of literate civilization and sources are scattered.

.png)

- From circa 500 BC we have Greek and Persian reports. The so-called Pointed-Hat Sakas may have lived along the upper Syr-darya and may have some connection to Ptolemy’s Sacaraucae. The Dahae lived between the Caspian and Aral Seas. The Massagatae probably lived east of the Aral Sea. Herodotus speaks vaguely of Issedones, Arimaspi, Hyperborians and others.

- From 125 BC we have Chinese reports. The Kangju lived along the Syr Darya and the Yancai probably north of the Aral Sea. The Yancai were possibly the Greek’s Sarmatians, and specifically the Alans. The above peoples were all independent of the Persian and Macedonian Empires to the south.

- Huns (before 370 AD): The Huns formed somewhere in Central Asia, crossed the Volga about 370 AD and raided the Roman Empire. They were probably a mixture of Xiongnu and other peoples.

- First Turkic Khaganate (552-659 AD): The first Turkic Khaganate formed in Mongolia and quickly spread to the Volga. It soon split and the central steppe became the Western Turkic Khaganate. It developed two factions, with the Dulu Turks south of lake Balkhash and the Nushibi between them and the Kangars east of the Aral Sea.

- Turkic migrations (c.500-1100):[1] If we group Turkic speakers by language family they moved west in three waves. Basically, the Oghurs disappeared, the Oghuz went southwest and left their languages in Turkmenistan and Turkey and the Kipchaks occupied the whole central and western steppe. The Karluks stayed home and moved somewhat southwest. Since our records refer to the ruling class we do not know how long Iranian languages survived among the common people on the steppe. South of the Syr Darya Turkic slave-soldiers began appearing about 800. This and other causes spread Turkic languages south of the Syr Darya, replacing most of the Iranian languages.

- Oghur: Circa 500, before the Turkic Khaganate, the Oghur may have been north of the Aral Sea and west of the Tiele. They continued west and founded several kingdoms around the western steppe. Their languages have disappeared except for the Chuvash language.

- Oghuz: About 700, after the fall of the Turkic Khaganate, the Oghuz Turks appear north of Lake Balkhash east of the Oghurs and west of the Karluks and Kipchaks. Before c. 900 they reached the Aral Sea and soon pushed south on both sides of the Aral Sea, possibly driven by the Kipchaks. Muslim Oghuz came to be known as Turkomans. Under the leadership of the Seljuks they pushed south and west, occupied Turkmenistan and gave their language and religion to modern Turkey. Oghuz who went west and fought Kievan Rus were called Pechenegs.

- Kipchak: Around 700, after the fall of the Turkic Khaganate, we find the Kipchaks in western Dzungaria north of the Karluks. Before 900 they had replaced the Oghuz north of Lake Balkhash and were somehow associated with the Kimeks to their north. By 1000 they reached the Aral Sea and by 1100 the Volga. They continued west and occupied the whole western steppe where they were known as Cumans and Polovtsi. They may have been ruled by the Kimeks at some point and the Cumans may be somewhat different. Starting about 1500 they were pushed off the western steppe by Russians and Ukrainians, but remained on the central steppe and became the Kazakhs.

_en.png)

- Four peoples on the lower Syr Darya: After the fall of the Gokturks the Kangar union (659–750?) was based on the lower Syr Darya. They may have been a revived Kangju under Turkic rule. The Pechenegs (750–790, very uncertain) were either Kangars or replaced them. From about 775 and 783[2] the Oghuz drove them west where they fought Kievan Rus. Circa 790 one of the Oghuz leaders took the title of Yabgu. Around 985 one of his subjects broke with the Yabgu and founded the Seljuks. The so-called Oghuz Yabgu State was overthrown by the Seljuks in 1043. They were followed by the Qangli who lasted until the Mongol conquest.

- Other Turkic peoples: The Kimek tribe lived north of the Kipchaks and moved west with them. Their ruler called himself Khan and he may have had some power over the Kipchaks. The Karluks remained in the east. The Qun (Kuns) (c. 1000-1100) were in western Dzungaria and around 1020 pushed the Kipchaks west. They either disappeared or reappeared in Hungary with the Kipchak/Cumans. The Tiele people were probably Turkic.

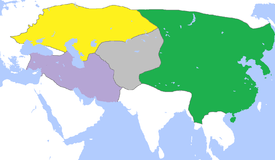

Mongols and after

- Mongols (1206-c. 1294): The Mongol Empire was founded in 1206, reached the Ural River about 1227 and reached the edge of western Europe by 1240.

- Golden Horde (c. 1241-c. 1504): The Mongol Empire gradually split into four parts. The western and central steppe became the Golden Horde. (But the Chagataids held Semirechye and, approximately, the land south of the Syr Darya.) Within a hundred years they adopted Islam and the Kipchak language of their subjects. They reached maximum power before 1350, decayed due to internal conflicts, lost outlying areas and broke up, the last khan dying about 1504.

- Sibir (c. 1405-1582): North of the main steppe and east of the Urals, the Khanate of Sibir lasted until it was conquered by the Russians as they began the conquest of Siberia.

- Abul-Khayr (c. 1428-67): As the Golden Horde was breaking up, Abu'l-Khayr Khan, a Shaybanid or descendent of Batu’s brother, briefly unified the area from the Aral Sea north toward Siberia and east toward Lake Balkash. The term Uzbek appears about this time, originally meaning something like Shaybanid and later applied to Turkic speakers along the Oxus.

- Kazakhs (c.1460–present): A group of Abu’l-Khayr’s people broke off and settled in Semirechye. They came to be called Uzbek-Kazakhs, meaning something like free Uzbeks. Because of the disturbances following Abu’l-Khayr’s death more Uzbeks joined them and the term Kazakh spread all over the central steppe. After about 1718 they divided into three Zhuzes. The Russians slowly gained power from 1730 and in 1845 the title of Khan was formally abolished. Kazakhstan became independent in 1991.

- Nogai: Around 1500 the Kipchaks north of the Caspian came to be called the Nogai Horde and their name spread to all the Kipchaks west of the Kazakhs. Those on the western steppe were slowly destroyed by the Russians while those on the central steppe seem to have been absorbed by the Kazakhs and Kalmyks.

- Kalmyks (1618–1771): The Kalmyks were Buddhist Mongols from Dzungaria. In 1618 they crossed the central steppe and settled north of the Caspian. In 1771 part of them returned to Dzungaria.

- Russians (c. 1743-1991): In 1582–1639 Russians made themselves masters of the Siberian forests. In 1743 they founded Orenburg on the Ural River from which they watched the steppe and slowly gained control of the Kazakh country. See Russian conquest of Turkestan. Some Russian peasants settled along the northern steppe. Western civilization in its Russian or Soviet form transformed daily life while the results of the industrial revolution made steppe nomadism economically and militarily obsolete. In 1953–62 the Virgin lands campaign brought a significant number of Russians and Ukrainians to northern Kazakhstan.

Sources and footnotes

- Since this is an overview article, sources, footnotes and details are best found in the linked articles. Standard sources for steppe history are:

- Yuri Bregel, Historical Atlas of Central Asia, 2003

- Rene Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, 1970

- Denis Sinor (editor), The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, 1990

- Cristoph Baumer, The History of Central Asia, 2012--, 3 volumes