Hippophae

| Hippophae | |

|---|---|

| Common sea buckthorn shrub in the Netherlands | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Elaeagnaceae |

| Genus: | Hippophae L. |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| |

Hippophae is a genus of sea buckthorns, deciduous shrubs in the family Elaeagnaceae. The name sea buckthorn may be hyphenated[1] to avoid confusion with the buckthorns (Rhamnus, family Rhamnaceae). It is also referred to as sandthorn, sallowthorn,[2] or seaberry.[3]

Taxonomy

In ancient times, leaves and young branches from sea buckthorn were supposedly fed as a remedy to horses to support weight gain and appearance of the coat, thus leading to the name of the genus, Hippophae derived from hippo (horse), and phaos (shining).[4]

Distribution

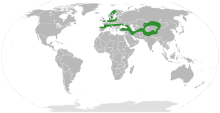

Hippophae rhamnoides, the common sea buckthorn, is by far the most widespread of the species in the genus, with the ranges of its eight subspecies extending from the Atlantic coasts of Europe across to northwestern Mongolia and northwestern China.[5][6] In western Europe, it is largely confined to sea coasts where salt spray off the sea prevents other larger plants from outcompeting it, but in central Asia, it is more widespread in dry semi-desert sites where other plants cannot survive the dry conditions.

In central Europe and Asia, it also occurs as a sub-alpine shrub above the tree line in mountains, and other sunny areas such as river banks where it has been used to stabilize erosion.[5] They are tolerant of salt in the air and soil, but demand full sunlight for good growth and do not tolerate shady conditions near larger trees. They typically grow in dry, sandy areas.

More than 90% or about 1,500,000 ha (5,800 sq mi) of the world's natural sea buckthorn habitat is found in China, Mongolia, Russia, northern Europe, and Canada, where the plant is used for soil, water and wildlife conservation, anti-desertification purposes, and consumer products.[5]

Sea buckthorn USDA hardiness zones are about 3 through 7.[5]

Description

The shrubs reach 0.5–6 metres (1.6–19.7 ft) tall, rarely up to 10 metres (33 ft) in central Asia. The leaf arrangement can be alternate or opposite.[7]

- Hippophae goniocarpa grows in mountainous regions in Nepal and China on mountain slopes, river banks, flood lands and valley terraces. The growth altitude is typically between 2650 and 3700 m. The species is divided into two distinct subspecies, H. goniocarpa subsp. litangensis and H. goniocarpa subsp. goniocarpa. H. goniocarpa subsp. litangensis differs from the typical subspecies by the young branchlets and the lower surface of leaves.[8] The Latin specific epithet goniocarpa refers to goniocarpus -a -um with angular fruits.[9]

- Hippophae gyantsensis

- Hippophae litangensis

- Hippophae neurocarpa

- Hippophae rhamnoides: Common sea buckthorn has dense and stiff branches, and are very thorny. The leaves are a distinct pale silvery-green, lanceolate, 3–8 cm (1.2–3.1 in) long, and less than 7 mm (0.28 in) broad. It is dioecious, with separate male and female plants. The male produces brownish flowers which produce wind-distributed pollen. The female plants produce orange berries 6–9 mm (0.24–0.35 in) in diameter, soft, juicy, and rich in oils. The roots distribute rapidly and extensively, providing a nonleguminous nitrogen fixation role in surrounding soils.

- Hippophae salicifolia (willow-leaved sea buckthorn) is restricted to the Himalayas, to the south of the common sea buckthorn, growing at high altitudes in dry valleys; it differs from H. rhamnoides in having broader (to 10 mm (0.39 in)) and greener (less silvery) leaves, and yellow berries. A wild variant occurs in the same area, but at even higher altitudes in the alpine zone. It is a low shrub not growing taller than 1 m (3.3 ft) with small leaves 1–3 cm (0.39–1.18 in) long.

- Hippophae tibetana

Varieties

During the Cold War, Russian and East German horticulturists developed new varieties with greater nutritional value, larger berries, different ripening months and branches that are easier to harvest. Over the past 20 years, experimental crops have been grown in the United States, one in Nevada and one in Arizona, and in several provinces of Canada.[10]

Genetics

A study of nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer sequence data[11] showed that the genus can be divided into three monophyletic clades:

- H. tibetana

- H. rhamnoides with the exception of H. rhamnoides ssp. gyantsensis (=H. gyantsensis)

- remaining species

A study using chloroplast sequences and morphology,[6] however, recovered only two clades:

- H. tibetana, H. gyantsensis, H. salicifolia, H. neurocarpa

- H. rhamnoides

Natural history

The fruit is an important winter food resource for some birds, notably fieldfares.

Leaves are eaten by the larva of the coastal race of the ash pug moth and by larvae of other Lepidoptera, including brown-tail, dun-bar, emperor moth, mottled umber, and Coleophora elaeagnisella.

Uses

Products

Sea buckthorn berries are edible and nutritious, though astringent, sour and oily, unpleasant to eat raw,[12] unless 'bletted' (frosted to reduce the astringency) and/or mixed as a drink with sweeter substances such as apple or grape juice. Additionally, malolactic fermentation of sea buckthorn juice reduces sourness, thus in general enhancing sensory properties. The mechanism behind this change is transformation of malic acid into lactic acid in microbial metabolism.[13]

When the berries are pressed, the resulting sea buckthorn juice separates into three layers: on top is a thick, orange cream; in the middle, a layer containing sea buckthorn's characteristic high content of saturated and polyunsaturated fats; and the bottom layer is sediment and juice.[14][15] Containing fat sources applicable for cosmetic purposes, the upper two layers can be processed for skin creams and liniments, whereas the bottom layer can be used for edible products such as syrup.[14]

Besides juice, sea buckthorn fruit can be used to make pies, jams, lotions, teas, fruit wines, and liquors. The juice or pulp has other potential applications in foods, beverages, or cosmetics products. Fruit drinks were among the earliest sea buckthorn products developed in China. Sea buckthorn-based juice is popular in Germany and Scandinavian countries. It provides a nutritious beverage, rich in vitamin C and carotenoids.

For its troops confronting extremely low temperatures (see Siachen), India's Defence Research Development Organization established a factory in Leh to manufacture a multivitamin herbal beverage based on sea buckthorn juice.[16]

The seed and pulp oils have nutritional properties that vary under different processing methods.[17] Sea buckthorn oils are used as a source for ingredients in several commercially available cosmetic products and nutritional supplements.

Landscape uses

Sea buckthorn is a popular garden and landscaping shrub with an aggressive basal shoot system used for barrier hedges and windbreaks, and to stabilize riverbanks and steep slopes. They have value in northern climates for their landscape qualities, as the colorful berry clusters are retained through winter.[18] Branches may be used by florists for designing ornaments.

In northwestern China, sea buckthorn shrubs have been planted on the bottoms of dry riverbeds to increase water retention of the soil, thus decreasing sediment loss. Because of increased moisture conservation of the soil and nitrogen-fixing capabilities of sea buckthorn, vegetation levels have increased in areas where sea buckthorn have been planted.[19][20] Sea buckthorn was once distributed free of charge to Canadian prairie farmers by PFRA to be used in shelterbelts.[21]

Folk medicine and research

Different parts of sea buckthorn have been used as folk medicine,[22][23] although there is no high-quality clinical evidence that such uses are safe or effective.[22][24] Berry oil, either taken orally as a dietary supplement or applied topically, is believed to be a skin softener.[22] In Indian, Chinese and Tibetan traditional medicines, sea buckthorn fruit may be added to medications in the belief it provides treatments for diseases.[23]

Organizations

In 2005, the "EAN-Seabuck" network between European Union states, China, Russia and New Independent States was funded by the European Commission to promote sustainable crop and consumer product development. In Mongolia, there is an active National Association of Seabuckthorn Cultivators and Producers.

The International Seabuckthorn Association, formerly the International Center for Research and Training on Seabuckthorn (ICRTS), was formed jointly in 1988 by the China Research and Training Center on Seabuckthorn, the Seabuckthorn Office of the Yellow River Water Commission, and the Shaanxi Seabuckthorn Development Office. From 1995 to 2000, ICRTS published the research journal, Hippophae, which appears to be no longer active.

See also

- Sea buckthorn oil

- Wolfberry, a native Asian plant occasionally mistaken for sea buckthorn

References

- ↑ "Sea buckthorn". The Wildlife Trusts. Archived from the original on 2013-07-23. Retrieved 23 July 2013.

- ↑ "Hippophae rhamnoides". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "PLANTS Profile for Hippophae rhamnoides (seaberry)". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- ↑ Singh, Virendra (2005). "Seabuckthorn (Hippophae L.) in traditional medicines". Seabuckthorn (Hippophae L.): A Multipurpose Wonder Plant, Vol. II. New Delhi, India: Daya Publishing House. pp. 505–521. ISBN 978-81-7035-415-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Li TSC (2002). Janick J, Whipkey A, eds. Product development of sea buckthorn (PDF). Trends in new crops and new uses. ASHS Press, Alexandria, VA. pp. 393–8. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- 1 2 Bartish, Igor V.; Jeppsson, Niklas; Nybom, Hilde; Swenson, Ulf (2002). "Phylogeny of Hippophae (Elaeagnaceae) inferred from parsimony analysis of chloroplast DNA and morphology". Systematic Botany. 2 (1): 41–54. doi:10.1043/0363-6445-27.1.41 (inactive 2018-09-11). JSTOR 3093894.

- ↑ Swenson, Ulf; Bartish, Igor V. (2002). "Taxonomic synopsis of Hippophae (Elaeagnaceae)". Nordic Journal of Botany. 22 (3): 369–374. doi:10.1111/j.1756-1051.2002.tb01386.x.

- ↑ Yongshan, Lian; Xuelin, Chen; Hong, Lian (2003). "Taxonomy of seabuckthorn (Hippophae L.)". Seabuckthorn (Hippophae L.): A Multipurpose Wonder Plant, Vol. I. New Delhi, India: Indus Publishing Company. pp. 35–46. ISBN 978-81-7387-156-6.

- ↑ D. Gledhill The Names of Plants, p. 192, at Google Books

- ↑ Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration Center, Sea-buckthorn: A promising multi-purpose crop for Saskatchewan, January 2008

- ↑ Sun, K.; Chen, X.; Ma, R.; Li, C.; Wang, Q.; Ge, S. (2002). "Molecular phylogenetics of Hippophae L. (Elaeagnaceae) based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences of nrDNA". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 235: 121–134. doi:10.1007/s00606-002-0206-0.

- ↑ Tiitinen, Katja M.; Hakala, Mari A.; Kallio, Heikki P. (March 2005). "Quality components of sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides) varieties". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 53 (5): 1692–1699. doi:10.1021/jf0484125. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 15740060.

- ↑ Tiitinen, Katja M.; Vahvaselkä, Marjatta; Hakala, Mari; Laakso, Simo; Kallio, Heikki (December 2005). "Malolactic fermentation in sea buckthorn (Hippophaë rhamnoides L.) juice processing". European Food Research and Technology. 222 (5–6): 686–691. doi:10.1007/s00217-005-0163-2. ISSN 1438-2377.

- 1 2 Seglina, D.; et al. (2006). "The effect of processing on the composition of sea buckthorn juice" (PDF). J Fruit Ornamental Plant Res. 14: 257–63. (Suppl 2)

- ↑ Zeb, A (2004). "Chemical and nutritional constituents of sea buckthorn juice" (PDF). Pakistan J Nutr. 3 (2): 99–106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-28.

- ↑ "Leh berries to dot Himalayan deserts by 2020". Archived from the original on 8 October 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ↑ Cenkowski S; et al. (2006). "Quality of extracted sea buckthorn seed and pulp oil". Can Biosystems Engin. 48 (3): 9–16.

- ↑ Kam, B.; N. Bryan (2003). The Prairie Winterscape: Creative Gardening for the Forgotten Season. Fifth House Ltd. pp. 108–10. ISBN 978-1-894856-08-9.

- ↑ Zhang, Kang; Xu, Mengzhen; Wang, Zhaoyin (2009). "Study on reforestation with seabuckthorn in the Pisha Sandstone area". Journal of Hydro-environment Research. 3 (2): 77–84. doi:10.1016/j.jher.2009.06.001. ISSN 1570-6443.

- ↑ Yang, Fang-She; Bi, Ci-Fen; Cao, Ming-Ming; Li, Huai-En; Wang, Xin-Hong; Wu, Wei (2014). "Simulation of sediment retention effects of the double seabuckthorn plant flexible dams in the Pisha Sandstone area of China". Ecological Engineering. 71: 21–31. doi:10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.07.050. ISSN 0925-8574.

- ↑ "Prairie Shelterbelt Program:Application for Trees" (PDF). Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013.

- 1 2 3 "Sea buckthorn". Drugs.com. 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- 1 2 Zeb, Alam (2004). "Important therapeutic uses of sea buckthorn (Hippophae): a review" (PDF). Journal of Biological Sciences. 4 (5): 687–693. ISSN 1727-3048.

- ↑ Sayegh, Marietta; Miglio, Cristiana; Ray, Sumantra (2014). "Potential cardiovascular implications of Sea Buckthorn berry consumption in humans". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 65 (5): 521–528. doi:10.3109/09637486.2014.880672. ISSN 0963-7486. PMID 24490987.

Further reading

- Beveridge, Thomas H. J.; Li, Thomas S. C. (2003). Sea buckthorn (Hippophae rhamnoides L.) production and utilization. Ottawa: NRC Research Press. ISBN 978-0-660-19007-5. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25.

- Li TSC, Oliver A. Sea buckthorn factsheet, British Columbia Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries, May 2001

- Todd, J. Introduction to sea-buckthorn, Ontario Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Rural Affairs, February, 2006

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Swallowthorn. |