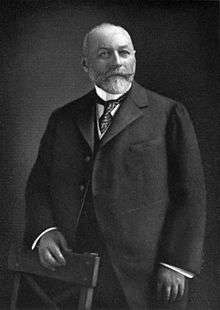

Herman Frasch

| Herman Frasch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

December 25, 1851 Oberrot bei Gaildorf, Württemberg |

| Died |

May 1, 1914 (aged 62) Paris |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Projects | Frasch Process |

| Awards | Perkin Medal (1912) |

Herman Frasch [or Hermann Frasch] (December 25, 1851 in Oberrot bei Gaildorf, Württemberg – May 1, 1914 in Paris) was a chemist, mining engineer and inventor known for his work with petroleum and sulphur.

Biography

Early life

He was the son of Johannes and Frieda Henrietta (Bauer) Frasch. Both his parents were natives of Stuttgart. His father was burgomaster of Gaildorf. Herman attended the Latin school in Gaildorf and was then apprenticed to a bookseller in nearby Schwäbisch Hall.[1]:47-53 At the age of 16 or 19, he left the apprenticeship and sailed from Bremen to New York, then took the train to Philadelphia.[1]:47-53 After his arrival in the United States, he became a lab assistant to John Michael Maisch at the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy.[2]:41

Engineering career

Oil career

In 1875, Frasch invented a recovery process for tin scrap and process to make white lead from galena. He patented a process for refining paraffin wax in 1876, and sold the patent to Standard Oil, for whom he became a consulting chemist based in Cleveland.[2]:41-42

In 1885 he bought the Empire Oil Company based in Petrolia, Ontario. The kerosene refined by Empire had a high sulfur content, producing a bad smell and excessive smoke. Frasch sweetened the sour crude through a patented desulphurization process. Recognizing Ohio and Indiana also produced sour crude, John D. Rockefeller bought Frasch's patents and company, using Standard stock, and made Frasch Standard's first director of research. Frasch was paid a salary, royalties, and allowed two months a year free for his own work ideas. Frasch became independently wealthy when he sold half his Standard stock, after the price rose from $168 to $820 per share, while the divided on the stock he retained increased from 7 to 40 per cent.[2]:41-42

Sulphur career

During the search for oil in Louisiana, near the present-day city of Sulphur, sulfur was found below a layer of quicksand. All attempts to get to the sulfur with conventional mining shafts ended in disaster. Herman Frasch drilled three dry holes nearby, but the sulfur was not on his property. Frasch concluded the sulfur was associated with a dome structure located on an island owned by the American Sulphur Company. On 20 Oct. 1890, he took out three patents for his Frasch Process. Frasch, and his business associates Frank Rockefeller and F.B. Squire, then entered into a 50-50 agreement with American Sulphur Company to form a new corporation called Union Sulphur Company.[2]

In 1894, Frasch started drilling well No. 14 using a 10 inch pipe, finally getting through the quicksand to the caprock after three months. He then drilled an 8 inch bore to the bottom of the sulphur deposit. A strainer, consisting of perforated 6 inch casing, was placed at the bottom of the 623 feet long test tube. Above the strainer were larger holes acting as the hot water outlet. A 3 inch pipe inside the 6 inch casing descended to the strainer, and was connected to a sucker rod pump. Water, from the surrounding swamp, was heated in a 20 feet high cylinder 30 inches in diameter, from steam supplied by 4 boilers. The superheated water was poured into the well for 24 hours, and on Christmas Day, melted sulphur was pumped to the surface filling 40 barrels in 15 minutes. The excess was then directed to a levee, where it solidified. As Frasch himself said about the first demonstration of the first Frasch Process, "We had melted the mineral in the ground and brought it to the surface as liquid."[2]:40-49

Frasch then eliminated the pump, by using air lift via compressed air. Bubbles form from the air, making the sulphur less dense than the surrounding water, thus raising the aerated column. Costs were also reduced by replacing wood and coal with oil. Then in 1911, he introduced bleed pumps to draw off excess cold water.[2]:53,61,96-97

In 1908, Frasch entered into an agreement with the Italian Government dividing the world market outside the U.S., where Union Sulphur Co. was guaranteed one-third. His costs were one-fifth that of Sicilian Sulphur mined in Caltanissetta. That agreement ended in 1912. Once his original patents expired, Frasch was unsuccessful in blocking Freeport Sulphur Company from using his process.[2]:67-68,71-73,82

Legacy

Frasch was awarded the Perkin Medal in 1912.[2]:48

Frasch Elementary school, a public school in Calcasieu Parish, and Frasch Hall, a building at McNeese State University were named after him. Frasch's surname is often misspelled Frash.

Herman Frasch died at his home in Paris on May 1, 1914 and was buried in Gaildorf. His body and that of his widow, Elizabeth Blee Frasch, were brought to the United States and re-interred in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Sleepy Hollow, New York following the death of Elizabeth in Paris in 1924 .[1]:242-243

Frasch was awarded 64 U.S. patents during his lifetime.[2]:43

References

Additional Reading

- "Obituaries - Herman Frasch, Paul L. V. Héroult". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 6 (6): 505–507. 1914. doi:10.1021/ie50066a024.

- Herman Frasch (1912). "The Perkin's Medal Award - Address of Acceptance". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 4 (2): 134–140. doi:10.1021/ie50038a016.

- Herman Frasch (1918). "UNVEILING OF THE PORTRAIT OF HERMAN FRASCH". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry. 10 (4): 326–327. doi:10.1021/ie50100a038.

- History of Sulphur (Sulphur, Louisiana)

- Stuart Bruchey (1960). "Brimstone, The Stone That Burns: The Story of the Frasch Sulphur Industry by Williams Haynes". Journal of Economic History. 20 (2): 326–327. JSTOR 2114864.

- Walter Botsch (2001). "Chemiker, Techniker, Unternehmer: Zum 150. Geburtstag von Hermann Frasch". Chemie in unserer Zeit. 35 (5): 324–331. doi:10.1002/1521-3781(200110)35:5<324::AID-CIUZ324>3.0.CO;2-9.

- Oskison, John M. (July 1914). "A Chemist Who Became King Of An Industry: Herman Frasch, The Greatest Of Oil-Refining Experts and Master, Through His Researches And Inventions, Of The Sulphur Supply Of The World". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. Doubleday, Page & Co. XXVIII (2): 310. Retrieved 2009-08-04.

- Attribution