Herleva

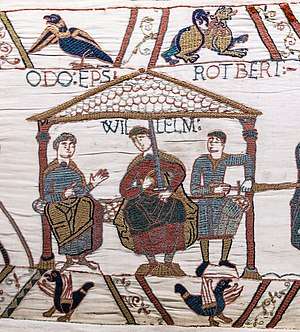

Herleva[lower-alpha 1] (c. 1003 – c. 1050) was a Norman woman of the 11th century, known for three sons: William I of England "the Conqueror", an illegitimate son fathered by Robert I, Duke of Normandy; and Odo of Bayeux and Robert, Count of Mortain, who were both fathered by her husband Herluin de Conteville. All three became prominent in William's realm.

Life

The background of Herleva and the circumstances of William's birth are shrouded in mystery. The written evidence dates from a generation or two later, and is not entirely consistent, but of all the Norman chroniclers only the Tours chronicler[lower-alpha 2] asserts that William's parents were subsequently joined in marriage.[lower-alpha 3] According to Edward Augustus Freeman the Tours chronicler's version can not be true, because if Hereleva married the Duke, then William's birth would have been legitimized, and thus he would not have been known as William the Bastard[lower-alpha 4], by his contemporaries.[5]

The most commonly accepted version says that she was the daughter of a tanner named Fulbert from the town of Falaise, in Normandy. The meaning of filia pelletarii burgensis[7] is somewhat uncertain, and Fulbert may instead have been a furrier, embalmer, apothecary, or a person who laid out corpses for burial.[8]

Some argue that Herleva's father was not a tanner but rather a member of the burgher class.[9] The idea is supported by the appearance of her brothers in a later document as attestors for an under-age William. Also, the Count of Flanders later accepted Herleva as a proper guardian for his own daughter. Both of these would be nearly impossible if Herleva's father was a tanner, which would place his standing as little more than a peasant.

Orderic Vitalis described Herleva's father Fulbert as the Duke's Chamberlain (cubicularii ducis).[10]

According to one legend, it all started when Robert, the young Duke of Normandy, saw Herleva from the roof of his castle tower.[11] The walkway on the roof still looks down on the dyeing trenches cut into stone in the courtyard below, which can be seen to this day from the tower ramparts above. The traditional way of dyeing leather or garments was to trample barefoot on the garments which were awash in the liquid dye in these trenches. Herleva, legend goes, seeing the Duke on his ramparts above, raised her skirts perhaps a bit more than necessary in order to attract the Duke's eye.[11] The latter was immediately smitten and ordered her brought in (as was customary for any woman that caught the Duke's eye) through the back door. Herleva refused, saying she would only enter the Duke's castle on horseback through the front gate, and not as an ordinary commoner. The Duke, filled with lust, could only agree. In a few days, Herleva, dressed in the finest her father could provide, and sitting on a white horse, rode proudly through the front gate, her head held high.[11][12] This gave Herleva a semi-official status as the Duke's concubine.[13] She later gave birth to his son, William, in 1027 or 1028.[14]

Some historians suggest Herleva was first the mistress of Gilbert of Brionne with whom she had a son, Richard. It was Gilbert who first saw Herleva and elevated her position and then Robert took her for his mistress.[15]

Marriage to Herluin de Conteville

Herleva later married Herluin de Conteville in 1031. Some accounts maintain that Robert always loved her, but the gap in their social status made marriage impossible, so, to give her a good life, he married her off to one of his favourite noblemen.[16]

Another source suggests that Herleva did not marry Herluin until after Robert died, because there is no record of Robert entering another relationship, whereas Herluin married another woman, Fredesendis, by the time he founded the abbey of Grestain.[17]

From her marriage to Herluin she had two sons: Odo, who later became Bishop of Bayeux, and Robert, who became Count of Mortain. Both became prominent during William's reign. They also had at least two daughters: Emma, who married Richard le Goz, Viscount of Avranches, and a daughter of unknown name who married William, lord of la Ferté-Macé.[18]

Death

According to Robert of Torigni, Herleva was buried at the abbey of Grestain, which was founded by Herluin and their son Robert around 1050. This would put Herleva in her forties around the time of her death.[lower-alpha 5]

Notes

- ↑ She was also known as Herleve,[1] Arlette,[2] Arletta[3] Arlotte,[4] and Harlette

- ↑ William of Malmesbury also suggests that Herleva married the Duke but it is believed that he just copied the Tour Chronicle version. [5]

- ↑ "Dux Robertus, nato dicto Guillelmo, in isto eodem anno matrem pueri, quam defloraverat, duxit in uxorem." (When the said William had been born, in that same year Duke Robert took as his wife the boy's mother, whom he had deflowered.) [5]

- ↑ He was regularly described as bastardus (bastard) in non-Norman contemporary sources.[6]

- ↑ David C. Douglas suggests that Herleva probably died before Herluin founded the abbey because her name does not appear on the list of benefactors, whereas the name of Herluin's second wife, Fredesendis, does.[19]

Sources

- ↑ David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 15

- ↑ Freeman, Edward A. The history of the Norman conquest of England, its causes and its result . Volume I. p. 530

- ↑ Palgrave, Sir Francis. The History of Normandy and of England (1864), p. 145

- ↑ Abbott, Jacob. William the Conqueror (1903), p. 41

- 1 2 3 Edward Augustus Freeman,The History of the Norman Conquest of England: II 2nd Ed. The reign of Eadward the Confessor. Note U: The Birth of William 1, p. 615.

- ↑ Bates,Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ↑ Chronicle of St-Maxentius quoted in Freeman. The History of the Norman Conquest of England: II. 2nd Ed. p. 611.

- ↑ van Houts, Elisabeth M. C., 'The Origins of Herleva, Mother of William the Conqueror', English Historical Review, vol. 101, pp. 399–404 (1986)

- ↑ McLynn, Frank. 1066: The Year of the Three Battles. pp. 21–23 (1999) ISBN 0-7126-6672-9

- ↑ van Houts, Elisabeth M. C., 'The Origins of Herleva, Mother of William the Conqueror', English Historical Review, vol. 101, pp. 399–404 (1986); Crouch, David 'The Normans- The History of a Dynasty' Hambledon 2002 at pp 52–53 and p58

- 1 2 3 Strittmatter. Our Ancestors: A Journey through the Generations. pp. 56-57

- ↑ Brownsworth. The Normans: From Raiders to Kings. pp. 33-34

- ↑ Harper-Bill. Anglo-Norman Studies: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1998. pp. 24-25

- ↑ Bates.William the Conqueror. p. 33.

- ↑ Simpkin. Herleva of Falaise. Retrieved 20 March 2017

- ↑ Tracy Borman. Matilda: Wife of the Conqueror. p. 22

- ↑ "Norman Nobility". Medieval Lands Project. Retrieved on 2009-07-30.

- ↑ David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 381

- ↑ David C. Douglas, William the Conqueror (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1964), p. 382

References

- Bates, David (2004). "William I (known as William the Conqueror)" ((subscription or UK public library membership required)). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29448. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- Bates, David (2001). William the Conqueror. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1980-3.

- Borman, Tracy (2011). Matilda: Wife of the Conqueror, First Queen of England. London: Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-0995-4913-1.

- Brownworth, Lars (2014). The Normans: From Raiders to Kings. United Kingdom: Crux publishing. ISBN 1-9099-7908-2.

- Damian-Grint, Damian (1999). Harper-Bill, Christopher, ed. "EN NUL LEU NEL TRUIS ESCRIT: RESEARCH AND INVENTION IN BENOIT DE SAINT MAURE'S CHRONIQUE DES DUCS DE NORMANDIE". Anglo-Norman Studies: Proceedings of the Battle Conference 1998. Woodbridge,Suffolk: Boydell Press. 21. ISBN 0-8511-5745-9.

- Freeman, Edward August (1867). The History of the Norman Conquest of England: its cause and results. I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 499740947.

- Freeman, Edward August (1870). The History of the Norman Conquest of England: The reign of Eadward the Confessor. Revised. II (2 ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 971506352.

- Simpkin, John (2014). "Herleva of Falaise". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Strittmatter, Rowena (2016). Our Ancestors: A Journey through the Generations. Hamburg, Germany: Tredition. ISBN 3-7323-8141-2.

External links

- Life of Harlette, or Herleva, mother of William the Conqueror (with images)