Herculaneum papyri

The Herculaneum papyri are more than 1,800 papyri found in the Herculaneum Villa of the Papyri, in the 18th century, carbonized by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79.

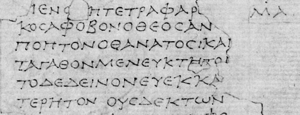

The papyri, containing a number of Greek philosophical texts, come from the only surviving library from antiquity that exists in its entirety.[1] Most of the works discovered are associated with the Epicurean philosopher and poet Philodemus of Gadara.

Discovery

Due to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79AD, bundles of scrolls were carbonized by the intense heat of the pyroclastic flows.[2] This intense parching took place over an extremely short period of time, in a room deprived of oxygen, resulting in the scrolls' carbonisation into compact and highly fragile blocks.[1] They were then preserved by the layers of cement-like rock.[2]

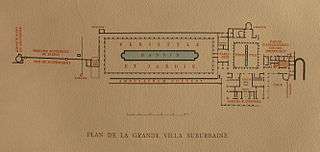

In 1752, workmen of the Bourbon royal family accidentally discovered what is now known as the Villa of the Papyri.[1][3] There may still be a lower section of the Villa's collection that remains buried.[2]

Barker noted in his 1908 Buried Herculaneum:[4]

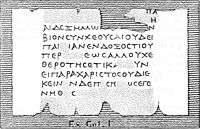

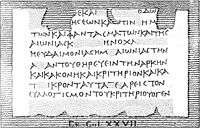

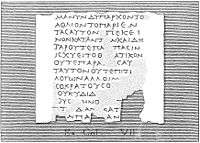

Appearance of the rolls. — A large number of papyri, after being buried eighteen centuries, have been found in the Villa named after them. In appearance the rolls resembled lumps of charcoal; and many were thrown away as such. Some were much lighter in colour. Finally, a faint trace of letters was seen on one of the blackened masses, which was found to be a roll of papyrus, disintegrated by decay and damp, full of holes, cut, crushed, and crumpled. The papyri were found at a depth of about 120 feet (37 metres).

The woodwork of some of the presses that had contained them dropped to dust on exposure and many rolls were found lying about loosely. Others were still on the shelves. Locality of the discovery. — They were found in four different places on four different occasions. The first were found in the autumn of 1752, fourteen years after the first discovery of Herculaneum, in and near the tablinum, and only numbered some 21 volumes and fragments, contained in two wooden cases. In the spring of 1753, 11 papyri were found in a room just south of the tablinum, and in the summer of the same year, 250 were found in a room to the north. In the spring and summer of the following year, 337 Greek papyri and 18 Latin papyri were found in the Library. Nothing of any importance was discovered after this date.

The numbers given here exclude mere fragments. Including every tiny fragment found, the catalogues give 1756 manuscripts discovered up to 1855, while subsequent discoveries bring the total up to 1806. Of these, 341 were found almost entire, 500 were merely charred fragments, and the remaining 965 were in every intermediate state of disintegration.

Treatment of the rolls. — No one knew how to deal with such strange material. Weber, the engineer, and Paderni, the keeper of the Museum at Portici, were not experts in palaeography and philology, which sciences were, indeed, almost in their infancy one hundred and fifty years ago. There were no official publications concerning the papyri till forty years after their discovery, and our information is of necessity incomplete, inexact and contradictory.

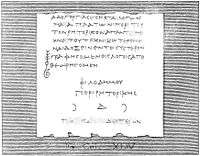

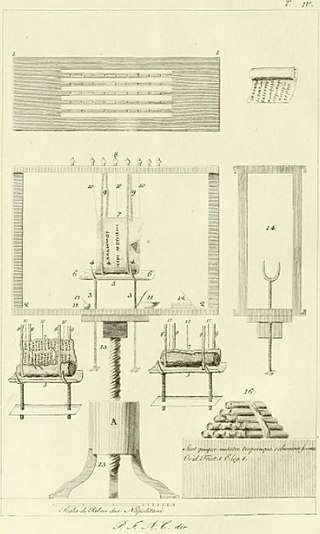

Father Piaggio's machine. — Through this inevitable ignorance of the time, a larger number of the rolls were destroyed than the difficulties of the case necessitated. Many had been thrown away as mere charcoal; some were destroyed in extracting them from the lava in which they were embedded. In the attempt to discover their contents, several were split in two longitudinally. Finally, that ingenious Italian monk. Father Piaggio, invented a very simple machine for unrolling the manuscripts by means of silk threads attached to the edge of the papyrus. Of course this method destroyed the beginning of all the papyri, sometimes the end could not be found, and the papyri were in a terrible state of decay.

Excavations

| “ | Anybody who focuses on the ancient world is always going to be excited to get even one paragraph, one chapter, more... The prospect of getting hundreds of books more is staggering. | ” |

| — Roger Macfarlane[2] | ||

In the 18th century, the first digs began. The excavation appeared closer to mining projects, as mineshafts were dug, and horizontal subterranean galleries were installed. Workers would place objects in baskets and send them back up.[1]

With the backing of Charles III of Spain (1716 – 1788), Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre headed the systematic excavation of Herculaneum with Karl Jakob Weber.[5]

Barker noted in his 1908 Buried Herculaneum, "By the orders of Francis I land was purchased, and in 1828 excavations were begun in two parts 150 feet apart, under the direction of the architect. Carlo Bonucci. In the year 1868 still further purchases of land were made, and excavations were carried on in an eastward direction till 1875. The total area now open measures 300 by 150 perches (1510 by 756 metres). The limits of the excavations to the north and east respectively are the modern streets of Vico di Mare and Vico Ferrara. It is here only that any portion of ancient Herculaneum may be seen in the open day."[4]

It is uncertain how many papyri were originally found as many of the scrolls were destroyed by workmen or when scholars extracted them from the volcanic tuff.[6]

The official list amounts to 1,814 rolls and fragments, of which 1,756 had been discovered by 1855. In the 90s it was reported that the inventory now comprises 1826 papyri,[7] with more than 340 are almost complete, about 970 are partly decayed and partly decipherable, and more than 500 are merely charred fragments.[3]

In 2016, academics asked in an open letter the Italian authorities to consider new excavations, since it is assumed that many more papyri may be buried at the site.[8]

Post-excavation history

In 1802, King Ferdinand IV of Naples offered six rolls to Napoleon Bonaparte in a diplomatic move. In 1803, along with other treasures, the scrolls were transported by Francesco Carelli. Upon receiving the gift, Bonaparte then gave the scrolls to Institut de France under charge of Gaspard Monge and Vivant Denon.[1]

In 1810, eighteen unrolled papyri were given to George IV, four of which he presented to the Bodleian Library; the rest are now mainly in the British Library.[3]

Unrolling

Since their discovery previous attempts used rose water, liquid mercury, vegetable gas, sulfuric compounds, papyrus juice, or a mixture of ethanol, glycerin, and warm water, in hopes to make scrolls readable.[10] According to Antonio de Simone and Richard Janko at first the papyri were mistaken for carbonized tree branches, some perhaps were thrown away or burnt to make heat.[11]

Early attempts

In 1756, Abbot Piaggio conserver of ancient manuscripts in the Vatican Library used a machine he also invented,[9] to unroll the first scroll, which took four years (millimeters per day).[12][11] The results were then swiftly copied (since the writing rapidly disappeared: see below), reviewed by Hellenist academics, and then corrected once more, if necessary, by the unrolling/copying team.[1]

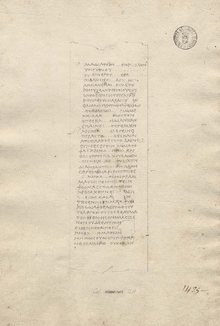

In 1802, King Ferdinand IV of Naples appointed Rev. John Hayter to assist the process.[1]

From 1802 to 1806, Hayter unrolled and partly deciphered some 200 papyri.[3] These copies are held in the Bodleian Library, where they are known as the "Oxford Facsimiles of the Herculaneum Papyri".[1]

In January 1816, Pierre-Claude Molard and Raoul Rochette led an attempt to unroll one papyrus with a replica of Abbot Piaggio's machine. However, the entire scroll was destroyed without any information being obtained.[1]

From 1819 until 1820, Humphry Davy was commissioned by the Prince Regent George IV to work on the Herculaneum papyri. Although it is considered that he has had only limited success, Davy's chemical method, using chlorine managed to partially unroll 23 manuscripts.[13]

In 1877, a papyrus was brought to a laboratory in the Louvre. An attempt to unravel it was made with a 'small mill', but it was unsuccessful and was partially destroyed - leaving a quarter intact.[1]

By the middle of the 20th century, only 585 rolls or fragments had been completely unrolled, and 209 unrolled in part. Of the unrolled papyri, about 200 had been deciphered and published, and about 150 only deciphered.[3]

Modern attempts

The bulk of the preserved manuscripts are housed in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

In 1969, Marcello Gigante founded the creation of the International Center for the Study of the Herculaneum Papyri (Centro Internazionale per lo Studio dei Papiri Ercolanesi; CISPE).[14] With the intention of working toward the resumption of the excavation of the Villa of the Papyri, and promoting the renewal of studies of the Herculaneum texts, the institution began a new method of unrolling. Using the 'Oslo' method, the CISPE team separated individual layers of the papyri. One of the scrolls exploded into 300 parts, and another did similarly but to a lesser extent.[1]

Since 1999, the papyri have been digitized by applying multi-spectral imaging (MSI) techniques. International experts and prominent scholars participated in the project. On 4 June 2011 it was announced that the task of digitizing 1,600 Herculaneum papyri had been completed.[15][16]

Since 2007, a team working with Institut de Papyrologie and group of scientists from Kentucky have been using x-rays and nuclear magnetic resonance to analyze the artifacts.[1]

In 2009, the Institut de France in conjunction with the French National Center for Scientific Research imaged two intact Herculaneum papyri using X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) to reveal the interior structures of the scrolls.[17][18] The team heading the project estimated that if the scrolls were fully unwound it would be between 36 and 49 feet long.[2] The internal structure of the rolls was revealed to be extremely compact and convoluted, defeating the automatic unwrapping computer algorithms that the team had developed. Manual examination of small segments of the internal structure of the rolls proved more successful, unveiling the individual fibres of the papyrus. Unfortunately, no ink could be seen on the small samples imaged, because the carbon-based ink are not visible on the carbonized scrolls.[2] However, some scrolls were written with ink containing lead.[19]

Virtual unrolling

According to Bukreeva et al. 2016, "The procedure of virtual unrolling can be divided into three main steps: volumetric scanning, segmentation, layered texture generation and restoration." Seales et al. 2005 and 2013, developed promising software that integrates functions of flattening and unrolling based on mass-spring surface simulations. Samko et al. 2014 proposed algorithms to solve problems of touching points between adjacent sheet layers.[20]

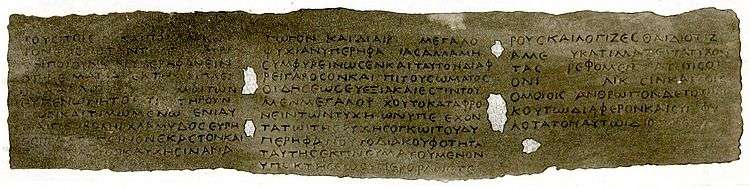

In 2015, a team led by Dr. Vito Mocella, from the National Research Council's Institute for Microelectronics and Microsystems (CNR-IMM),[21][22] has announced that "... X-ray phase-contrast tomography (XPCT) can reveal various letters hidden inside the precious papyri without unrolling them. [...] This pioneering research opens up new prospects not only for the many papyri still unopened, but also for others that have not yet been discovered, perhaps including a second library of Latin papyri at a lower, as yet unexcavated level of the Villa."[23] The microscopic relief of letters - a tenth of a millimetre[21] - on the papyri seems to be enough to create a noticeable phase contrast with the XPCT scans. This team was even able to identify some writing on a still-rolled scroll.[2] With the aim of making these scans cogent, a team is working with the National Science Foundation and Google to develop software which can sort through these displaced letters and figure out where they are located on the scroll.[2]

Following the pioneering results of Dr. Mocella et al., in 2016 another team led by Dr. G. Ranocchia and Dr. A. Cedola announced encouraging results by means of the non-destructive Synchrotron X-ray phase-contrast tomography (XPCT) technique.[24][20]

In September 2016, a method pioneered by University of Kentucky computer scientist W. Brent Seales was successfully used to unlock the text of Dead Sea Scrolls.[25] According to experts, this new method devised by Dr. Seales may make it possible to read the carbonized scrolls from Herculaneum.

Difficulties

| “ | What we see is that the ink, which was essentially carbon based, is not very different from the carbonised papyrus. | ” |

| — Dr. Vito Mocella[21] | ||

Opening a scroll would often damage or destroy the scroll completely. If a scroll had been successfully opened, the original ink - exposed to air - would begin to fade. In addition, this form of unrolling often would leave pages stuck together omitting or destroying additional information.[2]

With X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), no ink can be seen as carbon-based ink is not visible on carbonized papyrus.[2]

Significance

Until the middle of the 18th century, the only papyri known were a few survivals from medieval times.[26] Most likely, these rolls would never have survived the Mediterranean climate and would have crumbled or been lost. Indeed, all these rolls have come from the only surviving library from antiquity that exists in its entirety.[1]

These papyri contain a large number of Greek philosophical texts. Large parts of Books XIV, XV, XXV, and XXVIII of the magnum opus of Epicurus, On Nature and works by early followers of Epicurus are also represented among the papyri.[14] Of the rolls, 44 have been identified as the work of Philodemus of Gadara, an Epicurean philosopher and poet. The manuscript "PHerc.Paris.2" contains part of Philodemus' On Vices and Virtues.[1]

The Stoic philosopher Chrysippus is attested to have written over 700 works,[27] all of them lost, with the exception of a few fragments quoted by other authors.[28] Segments of his works On Providence and Logical Questions were found among the papyri;[28] a third work of his may have been recovered from the charred rolls.[29]

Parts of a poem on the Battle of Actium have also survived in the library.[30]

Additional images

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Interview with Daniel Delattre: the Herculaneum scrolls given to Consul Bonaparte (2010), Napoleon.org Archived 2015-10-30 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "History, Travel, Arts, Science, People, Places - Smithsonian". smithsonianmag.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Diringer, David (1982). The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 252–6. ISBN 0-486-24243-9.

- 1 2 Ethel Ross Barker (1908). "Buried Herculaneum".

- ↑ "Since the Re-discovery - AD79eruption". google.com.

- ↑ Banerji, Robin (20 Dec 2013). "Unlocking the scrolls of Herculaneum". BBC News. British Broadcasting Company. Retrieved 5 Jan 2017.

- ↑ (1986) IV. The Herculaneum Papyri, Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 33, pp. 36–45

- ↑ "Academics urge Italian authorities to excavate a library buried by Vesuvius they believe is packed with priceless historic texts". DailyMail. 2016.

- 1 2 Giacomo Castrucci (1858). "Tesoro letterario di Ercolano, ossia, La reale officina dei papiri ercolanesi".

- ↑ "The Invisible Library". The New Yorker. 2015.

- 1 2 "Out of the Ashes - Recovering the Lost Library of the Herculaneum". PBS. 2004.

- ↑ "Herculaneum Papyri in the National Library in Naples". The Phraser. 2015.

- ↑ Page 203 of Davy, Humphry (1821). "Some Observations and Experiments on the Papyri Found in the Ruins of Herculaneum". Philosophical Transactions. 111: 191–208. doi:10.1098/rstl.1821.0016.

- 1 2 CISPE Il Centro Internazionale per lo Studio dei Papiri Ercolanesi

- ↑ Digitization of Herculaneum Papyri Completed Insights 22/6 (2002) Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young U.

- ↑ BYU Herculaneum Project Honored with Mommsen Prize Insights 30/1 (2010) Maxwell Institute, Brigham Young U.

- ↑ EDUCE: Imaging the Herculaneum Scrolls (Video). Center for Visualization & Virtual Environments, U. Kentucky. 2011.

- ↑ W. Brent Seales, James Griffioen, Ryan Baumann, Matthew Field (2011) ANALYSIS OF HERCULANEUM PAPYRI WITH X-RAY COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY Center for Visualization & Virtual Environments; U. Kentucky

- ↑ Brun et al. (2016). "Revealing metallic ink in Herculaneum papyri". PNAS. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.3751B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1519958113.

- 1 2 Bukreeva I, et al. (2016). "Virtual unrolling and deciphering of Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast tomography". Scientific Reports. 6. Bibcode:2016NatSR...630364B. doi:10.1038/srep30364.

- 1 2 3 Jonathan Webb X-ray technique reads burnt Vesuvius scroll BBC News, Science & Environment, 20 January 2015

- ↑ Vergano, Dan (January 22, 2015). "X-Rays Reveal Snippets From Papyrus Scrolls That Survived Mount Vesuvius". National Geographic.

- ↑ Mocella, Vito; Brun, Emmanuel; Ferrero, Claudio; Delattre, Daniel (2015). "Revealing letters in rolled Herculaneum papyri by X-ray phase-contrast imaging". Nature Communications. 6: 5895. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6E5895M. doi:10.1038/ncomms6895.

- ↑ Bukreeva, I.; et al. (2016). "Enhanced X-ray-phase-contrast-tomography brings new clarity to the 2000-year-old 'voice' of Epicurean philosopher Philodemus". arXiv:1602.08071.

- ↑ Wade, Nicholas. "Modern Technology Unlocks Secrets of a Damaged Biblical Scroll", New York Times (September 21, 2016).

- ↑ Frederic G. Kenyon, Palaeography of Greek papyri (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1899), p. 3.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, vii. 180

- 1 2 John Sellars, Stoicism. University of California Press, 2007. - p. 8

- ↑ "The first of Chrysippus' partially preserved two or three works is his Logical Questions, contained in PHerc. 307 ... The second work is his On Providence, preserved in PHerc 1038 and 1421 ... A third work, most likely by Chrysippus is preserved in PHerc. 1020," Fitzgerald 2004, p. 11

- ↑ Gregory Hays, "Keeping Things Platonic: A new discovery of a possible lost book by Apuleius on Plato" [review of Justin A Stover, A New Work by Apuleius], Times Literary Supplement 20 May 2016 p. 29.

Further reading

- Armstrong, David. 2011. "Epicurean Virtues, Epicurean Friendship: Cicero vs. The Herculaneum Papyri." In Epicurus and the Epicurean Tradition. Edited by Jeffrey Fish and Kirk R. Sanders. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press

- Blank, David. 1999. "Reflections on Re-reading Piaggio and the Early History of the Herculaneum Papyri." Cronache Ercolanesi 29:55–82.

- Booras, Steven W., and David R. Seely. 1999. "Multispectral Imaging of the Herculaneum Papyri." Cronache Ercolanesi 29:95–100.

- Houston, George W. 2013. "The Non-Philodemus Book Collection in the Villa of the Papyri." In Ancient Libraries Edited by Jason König, Katerina Oikonomopoulou, Greg Woolf, 183-208. Cambridge; New York : Cambridge University Press.

- Janko, Richard. 1993. Philodemus Resartus: Progress in Reconstructing the Philosophical Papyri from Herculaneum. In Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy: VII, 1991. Edited by John J. Cleary. Lanham, Md. & London: University Press of America.

- Janko, Richard, and David Blank. 1998. "Two New Manuscript Sources for the Texts of the Herculaneum Papyri." Cronache Ercolanesi 28:173–184.

- Kleve, Knut. 1996. "How to Read an Illegible Papyrus: Towards an Edition of PHerc. 78, Caecilius Statius, Obolostates sive faenerator." Cronache Ercolanesi 26:5–14.

- Seales, W. Brent, Jim Griffioen, and David Jacobs. 2011. "Virtual Conservation: Experience with Micro-CT and Manuscripts." In Eikonopoiia: Digital Imaging of Ancient Textual Heritage: Proceedings of the International Conference, Helsinki, 28–29 November 2010. Edited by Vesa Vahtikari, Mika Hakkarainen, and Antti Nurminen, 81–88. Helsinki: Societas Scientiarum Fennica.

- Sider, David. 2005. The Library of the Villa dei Papiri at Herculaneum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum

- Zarmakoupi, Mantha, ed. 2010. The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum: Archaeology, Reception, and Digital Reconstruction. Berlin: de Gruyter.

External links

- Bodleian Library MS. Gr. class. b. 1 (P)/1-12

- Rawson, C., ed. Out of the Ashes: Recovering the Lost Library of Herculaneum. DVD. 2003. Provo, UT: Brigham Young University.

- BYU Herculaneum Project Honored with Mommsen Prize

- Wüerzburg Center for Epicurean Studies

- Porter, James I., Hearing Voices: The Herculaneum Papyri and Classical Scholarship

- UCLA Department of Classics: The Philodemus Project

- The Friends of Herculaneum Society

- An incomplete list of papyri from Herculaneum with high resolution photographs.