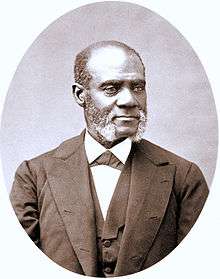

Henry Highland Garnet

| Henry H. Garnet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

December 23, 1815 New Market, Maryland, U.S. |

| Died |

February 13, 1882 (aged 66) Monrovia, Liberia |

| Nationality | American |

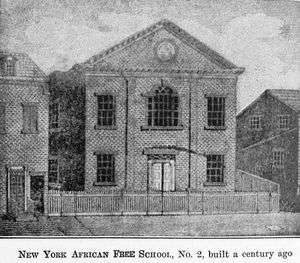

| Alma mater | African Free School |

| Occupation | Minister (Christianity), Abolitionist |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

Henry Highland Garnet (December 23, 1815 – February 13, 1882) was an African-American abolitionist, minister, educator and orator. Having escaped with his family as a child from slavery in Maryland, he grew up in New York City. He was educated at the African Free School and other institutions, and became an advocate of militant abolitionism. He became a minister and based his drive for abolitionism in religion.

Garnet was a prominent member of the movement that led beyond moral suasion toward more political action. Renowned for his skills as a public speaker, he urged black Americans to take action and claim their own destinies. For a period, he supported emigration of American free blacks to Mexico, Liberia, or the West Indies, but the American Civil War ended that effort. In 1841 he married abolitionist Julia Williams and they had a family. They moved to Jamaica in 1852 to serve as missionaries and educators. After the war, the couple worked in Washington, DC.

Early life and education

Henry Garnet was born into slavery in New Market, Kent County, Maryland, on December 23, 1815. According to James McCune Smith, Garnet's father was George Trusty and his enslaved mother was "a woman of extraordinary energy."[1] In 1824, the family, which included a total of 11 members, secured permission to attend a funeral, and from there, they all escaped in a covered wagon, first reaching Wilmington, Delaware.

When Garnet was ten years old, his family reunited and moved to New York City, where from 1826 through 1833, Garnet attended the African Free School, and the Phoenix High School for Colored Youth. While in school, Garnet began his career in abolitionism. His classmates at the African Free School included Charles L. Reason, George T. Downing, and Ira Aldridge.[2]

In 1834, Garnet joined William H. Day and David Ruggles to establish the all-male Garrison Literary and Benevolent Association. It garnered mass support among whites, but the club ultimately had to move due to racist feelings. One year later, in 1835, he started studies at the Noyes Academy in Canaan, New Hampshire. Anti-abolitionists and segregationist protested and eventually forced the academy to close after a mob of them attacked it.

He completed his education at the Oneida Theological Institute in Whitesboro, New York, which had recently admitted all races. Here he was acclaimed for his wit, brilliance, and rhetorical skills. The year after graduation in 1839, he injured his knee playing sports. It never recovered, and his lower leg had to be amputated in 1841.[2]

Marriage and family

In 1841 Garnet married Julia Williams, whom he had met as a fellow student at the Noyes Academy. She had also completed her education at the Oneida Institute. Together they had three children, only one of whom survived to adulthood.[2]

Ministry

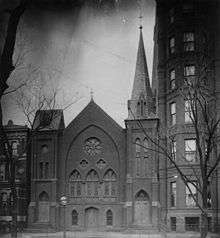

In 1839, Garnet moved with his family to Troy, New York, where he taught school and studied theology. In 1842, Garnet became pastor of the Liberty Street Presbyterian church, a position he held for six years. During this time, he published papers that combined religious and abolitionist themes. Closely identifying with the church, Garnet supported the temperance movement and became a strong advocate of political antislavery.[2]

He later returned to New York City, where he joined the American Anti-Slavery Society and frequently spoke at abolitionist conferences. One of his most famous speeches, "Call to Rebellion," was delivered August 1843 to the National Negro Convention in Buffalo, New York. "Upon the conclusion of the Negro national convention of 1843, Garnet led a state convention of Negroes assembled in Rochester."[3]

These conventions by black activists were called to work for abolition and equal rights. Garnet said that slaves should act for themselves to achieve total emancipation. He promoted an armed rebellion as the most effective way to end slavery. Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, along with many other abolitionists both black and white, thought Garnet's ideas were too radical and could damage the cause by arousing too much fear and resistance among whites. Garnet supported the Liberty Party, a party of reform that was eventually absorbed into the Republican Party. Garnet disagreed with the later Republicans.

Anti-slavery role

Women's participation in the abolitionist movement was controversial and resulted in a split in the American Anti-Slavery Society. Arthur Tappan, Lewis Tappan "and a group of black ministers, including Henry Highland Garnet" founded the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (AFAS).[4] It "was committed to political abolitionism and to male leadership at the top levels."[5]

By 1849 Garnet began to support emigration of blacks to Mexico, Liberia, or the West Indies, where he thought they would have more opportunities. In support of this, he founded the African Civilization Society. Similar to the British African Aid society, it sought to establish a West African colony in Yoruba (present-day Nigeria). Garnet advocated a kind of black nationalism in the United States, which included establishing separate sections of the nation to be black colonies. Other prominent members of this movement included minister Daniel Payne, J. Sella Martin, Rufus L. Perry, Henry M. Wilson, and Amos N. Freeman.[6]

In 1850, Garnet went to Great Britain at the invitation of Anna Richardson of the Free produce movement, which opposed slavery by rejecting the use of products produced by slave labor.[7] He was a popular lecturer, and spent two and a half years lecturing.

In 1852 Garnet was sent to Kingston, Jamaica, as a missionary. He and his family spent three years there; his wife Julia Garnet led an industrial school for girls. Garnet had health problems that led to the family returning to the United States.

When the American Civil War started, Garnet's hopes ended for emigration as a solution for American blacks. He worked to organize black army units to aid the Union cause. In the three-day New York draft riots of July 1863, mobs attacked blacks and black-owned buildings. Garnet and his family escaped attack because his daughter quickly chopped their nameplate off their door before the mobs found them.[8] He organized a committee for sick soldiers and served as almoner to the New York Benevolent Society for victims of the mob.[2]

When the federal government approved creating black units, Garnet helped with recruiting United States Colored Troops. He moved with his family to Washington, DC, so that he could support the black soldiers and the war effort. He preached to many of them while serving as pastor of the prominent Liberty (Fifteenth) Street Presbyterian Church from 1864 until 1866. During this time, Garnet was the first black minister to preach to the US House of Representatives, addressing them on 12 February 1865 about the end of slavery .

Later life

After the war in 1868, Garnet was appointed president of Avery College in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Later he returned to New York City as a pastor at the Shiloh Presbyterian Church (formerly the First Colored Presbyterian Church, and now St. James Presbyterian Church in Harlem).[2]

His first wife Julia died. In 1879, Garnet married Sarah Smith Tompkins, who was a New York teacher and school principal, suffragist, and community organizer.[9]

Garnet's last wish was to go to Liberia to live, even for a few weeks, and to die there. He was appointed as the U.S. Minister to Liberia in late 1881, and died in Africa two months later. Garnet was given a state funeral by the Liberian government and was buried at Palm Grove Cemetery in Monrovia.[10] Frederick Douglass, who had not been on speaking terms with Garnet for many years because of their differences, still mourned Garnet's passing and noted his achievements.

Legacy and honors

- 1952, Garnet's portrait was included among those in Civil Rights Bill Passes, 1866, a mural painted in the Hall of Capitols, the Cox Corridors of the Capitol building in Washington, DC. It was painted by Allyn Cox.

- P.S. 175 or the Henry Highland Garnet School for Success in Harlem, as well as the HHG Elementary School in Chestertown, Maryland, are named for him.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Henry Highland Garnet on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[11]

- The Garnett School built at 10th and U, NW in Washington, DC was named in his honor in 1880. It was merged with the Patterson school in a new building erected in 1929 and renamed Shaw Middle School at Garnett-Patterson. It was closed in 2013.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Smith, James McCune (1865). Introduction. A memorial discourse; by Henry Highland Garnet, delivered in the hall of the House of Representatives, Washington City, D.C. on Sabbath, February 12, 1865. With an introduction, by James McCune Smith, M.D. By Henry Highland Garnet. Philadelphia: Joseph Wilson. p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. p656-661

- ↑ Schor, Joel (1977). Henry Highland Garnet : a voice of black radicalism in the nineteenth century. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 61. ISBN 0837189373.

- ↑ White, Deborah Gray; Bay, Mia; Martin, Waldo E., Jr. (2013). Freedom on my mind : a history of African Americans, with documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 284. ISBN 9780312648831.

- ↑ Jr, Deborah Gray White, Mia Bay, Waldo E. Martin (2013). Freedom on my mind: A History of African Americans, with documents. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 284. ISBN 9780312648831.

- ↑ Taylor, Clarence. The Black Churches of Brooklyn, Columbia University Press, 1994. p19, 26

- ↑ Holcomb, Julie L. (1 Sep 2016). Moral Commerce: Quakers and the Transatlantic Boycott of the Slave Labor Economy. Cornell University Press. p. 189.

- ↑ Schecter, Barnet. The Devil's Own Work: The Civil War Draft Riots and the Fight to Reconstruct America. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2009. p154

- ↑ Polcino, Christine Ann (Fall 2004). "Biography: Garnet, Henry Highland". Literary and Cultural Heritage Map of Pennsylvania Writers. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Barnes, Kenneth C. (2004). Journey of Hope: The Back-to-Africa Movement in Arkansas in the Late 1800s. UNC Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-8078-2879-3.

- ↑ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia, Amherst, New York. Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-57392-963-8.

References

Bibliography

- Piersen, William Dillon, Black Legacy: America's Hidden Heritage, University of Massachusetts Press, 1993, ISBN 0-87023-859-0

James Jasinski "Constituting Antebellum African American Identity: Resistance, Violence, and Masculinity in Henry Highland Garnet's (1843) 'Address to the Slaves,'" Quarterly Journal of Speech, 93 (2007): 27-57.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Henry Highland Garnet. |

- Article, Star Tribune

- Henry H. Garnet, "An Address to the Slaves of the United States of America", Buffalo, NY, 1843, Digital Commons

- Henry H. Garnet, "The Past and the Present Condition, and the Destiny, of the Colored Race" (1848), Digital Commons

- Works by Henry Highland Garnet at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Henry Highland Garnet at Internet Archive

- Underground Workshop

- Spartacus Educational

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by John H. Smyth |

United States Minister to Liberia June 30, 1881 – February 13, 1882 |

Succeeded by John H. Smyth |