Henrietta Swan Leavitt

| Henrietta Swan Leavitt | |

|---|---|

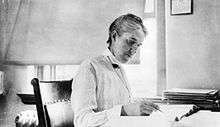

Henrietta Swan Leavitt | |

| Born |

July 4, 1868 Lancaster, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

December 12, 1921 (aged 53) Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Residence | Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Nationality | American |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Radcliffe College, Oberlin College |

| Known for | Leavitt's Law: the period–luminosity relationship of Cepheid stars |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | Harvard University |

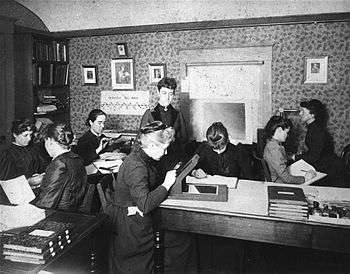

Henrietta Swan Leavitt (/ˈlɛvɪt/; July 4, 1868 – December 12, 1921) was an American astronomer who discovered the relation between the luminosity and the period of Cepheid variable stars. A graduate of Radcliffe College, Leavitt started working at the Harvard College Observatory as a "computer" in 1893, examining photographic plates in order to measure and catalog the brightness of the stars. Though she received little recognition in her lifetime, it was her discovery that first allowed astronomers to measure the distance between the Earth and faraway galaxies.[1] She explained her discovery: "A straight line can readily be drawn among each of the two series of points corresponding to maxima and minima, thus showing that there is a simple relation between the brightness of the variables and their periods."[2]

After Leavitt's death, Edwin Hubble used the luminosity–period relation for Cepheids, together with spectral shifts first measured by fellow astronomer, Vesto Slipher, at Lowell Observatory to determine that the universe is expanding (see Hubble's law).

Early years and education

Henrietta Swan Leavitt was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, the daughter of Congregational church minister George Roswell Leavitt[3] and his wife Henrietta Swan Kendrick. She was a descendant of Deacon John Leavitt, an English Puritan tailor, who settled in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the early seventeenth century.[4] (The family name was spelled Levett in early Massachusetts records.)

She attended Oberlin College and in 1892, was graduated from Radcliffe College, then called the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women, with a bachelor's degree. She studied a broad curriculum, including classical Greek, fine arts, philosophy, analytic geometry, and calculus.[5] It wasn't until her fourth year of college that Leavitt took a course in astronomy, in which she earned an A–.[6]:27 She then traveled in America and in Europe, during which time she lost her hearing.[7]

Career

In 1892, she was graduated from Harvard University's Radcliffe College, then was known as the Society for the Collegiate Instruction of Women.[8] In 1893, she obtained credits toward a graduate degree in astronomy for work completed at the Harvard College Observatory. She never completed the degree.[9] It was at the Harvard College Observatory that Leavitt began working as one of the women human "computers" hired by Edward Charles Pickering to measure and catalog the brightness of stars as they appeared in the observatory's photographic plate collection. (In the early 1900s, women were not allowed to operate telescopes.)[10] One of the women that Leavitt worked with in the Harvard Observatory was Annie Jump Cannon who shared the experience of being deaf[11]. Because Leavitt had independent means, Pickering initially did not have to pay her. Later, she received $0.30 an hour for her work,[6]:32 being paid only $10.50 per week. She was reportedly "hard-working, serious-minded …, little given to frivolous pursuits and selflessly devoted to her family, her church, and her career."[5]

Pickering assigned Leavitt to study variable stars, whose luminosity varies over time. According to science writer Jeremy Bernstein, "variable stars had been of interest for years, but when she was studying those plates, I doubt Pickering thought she would make a significant discovery—one that would eventually change astronomy."[12] Leavitt noted thousands of variable stars in images of the Magellanic Clouds. In 1908 she published her results in the Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College,[13] noting that a few of the variables showed a pattern: brighter ones appeared to have longer periods. After further study, she confirmed in 1912 that the Cepheid variables with greater intrinsic luminosity did have longer periods, and that the relationship was quite close and predictable.[2]

Leavitt used the simplifying assumption that all of the Cepheids within each Magellanic Cloud were at approximately the same distance from Earth, so that their intrinsic brightness could be deduced from their apparent brightness (as measured from the photographic plates) and from the distance to each of the clouds. "Since the variables are probably at nearly the same distance from the Earth, their periods are apparently associated with their actual emission of light, as determined by their mass, density, and surface brightness."[2]

Pickering assigned her to the study of variable stars of the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds recorded on photographic plates taken with the Bruce Astrograph of the Boyden Station of Harvard Observatory at Arequipa, Peru. She identified 1777 variable stars and discovered that the brighter ones had the larger period, a discovery known as the "period–luminosity relationship" or "Leavitt's law": The logarithm of the period is linearly and directly related to the logarithm of the star's average intrinsic optical luminosity (which is the amount of power radiated by the star in the visible spectrum).[15] In Leavitt's words, "A straight line can be readily drawn among each of the two series of points corresponding to maxima and minima, thus showing that there is a simple relation between the brightness of the Cepheid variables and their periods."[2][16]

Leavitt also developed, and continued to refine, the Harvard Standard for photographic measurements, a logarithmic scale that orders stars by brightness over 17 magnitudes. She initially analyzed 299 plates from 13 telescopes to construct her scale, which was accepted by the International Committee of Photographic Magnitudes in 1913.[17]

Influence

The period–luminosity relationship for Cepheids made them the first "standard candle" in astronomy, allowing scientists to compute the distances to galaxies too remote for stellar parallax observations to be useful. One year after Leavitt reported her results, Ejnar Hertzsprung determined the distance of several Cepheids in the Milky Way and that, with this calibration, the distance to any Cepheid could be accurately determined.[18]

Cepheids were soon detected in other galaxies, such as Andromeda (notably by Edwin Hubble in 1923–24), and they became an important part of the evidence that "spiral nebulae" are independent galaxies located far outside of our own Milky Way. Thus, Leavitt's discovery would forever change our picture of the universe, as it prompted Harlow Shapley to move our Sun from the center of the galaxy in the "Great Debate" and Edwin Hubble to move our galaxy from the center of the universe.

The accomplishments of Edwin Hubble, the American astronomer who established that the universe is expanding, also were made possible by Leavitt's groundbreaking research. Hubble often said that Leavitt deserved the Nobel Prize for her work.[19] Gösta Mittag-Leffler of the Swedish Academy of Sciences tried to nominate her for that prize in 1924, only to learn that she had died of cancer three years earlier.[20] (The Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously.)[21] Her discovery of a way to accurately measure distances on an inter-galactic scale, paved the way for modern astronomy's understanding of the structure and scale of the universe.[5]

Illness and death

Leavitt worked sporadically during her time at Harvard, often sidelined by health problems and family obligations. An illness contracted after her graduation from Radcliffe College rendered her increasingly deaf.[14] In 1921, when Harlow Shapley took over as director of the observatory, Leavitt was made head of stellar photometry. By the end of that year she had succumbed to cancer, and was buried in the Leavitt family plot at Cambridge Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[6]:89

"Sitting at the top of a gentle hill," writes George Johnson in his biography of Leavitt, "the spot is marked by a tall hexagonal monument, on top of which sits a globe cradled on a draped marble pedestal. Her uncle Erasmus Darwin Leavitt and his family also are buried there, along with other Leavitts. ..." A plaque memorializing Henrietta and her two siblings, Mira and Roswell, is mounted on one side of the monument. Nearby are the graves of Henry and William James.[6]:90 There is no epitaph at the gravesite memorializing Henrietta Leavitt's achievements in astronomy.

Leavitt was a member of Phi Beta Kappa, the American Association of University Women, the American Astronomical and Astrophysical Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and an honorary member of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. Her early death was seen as a tragedy by her colleagues for reasons that went beyond her scientific achievements. In an obituary her colleague, Solon I. Bailey, noted that "she had the happy faculty of appreciating all that was worthy and lovable in others, and was possessed of a nature so full of sunshine that, to her, all of life became beautiful and full of meaning."[6]:28

Awards and honors

- The asteroid 5383 Leavitt and the crater Leavitt on the Moon are named after her to honor deaf men and women who have worked as astronomers.[22][23]

- Unaware of her death four years prior, the Swedish mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler considered nominating her for the 1926 Nobel Prize in Physics, and wrote to Shapley requesting more information on her work on Cepheid variables, offering to send her his monograph on Sofia Kovalevskaya. Shapley replied, letting Mittag-Leffler know that Leavitt had died, and suggesting that the true credit belonged to his (Shapley's) interpretation of her findings. She was never nominated, because the Nobel Prize is not awarded posthumously.[6]:118

- One of ASAS-SN telescopes, located in the McDonald Observatory in Texas, is named in her honor.

Books and plays

Lauren Gunderson wrote a play, Silent Sky, which followed Leavitt's journey from her acceptance at Harvard to her death.[24]

George Johnson wrote a biography, Miss Leavitt's Stars, which showcases the triumphs of women's progress in science through the story of Leavitt.[25]

Robert Burleigh wrote the biography Look Up!: Henrietta Leavitt, Pioneering Woman Astronomer for a younger audience. It is written for four to eight year olds.[26]

See also

References

- ↑ "Leavitt, Henrietta Swan (1868-1921) | The Hutchinson Dictionary of Scientific Biography - Credo Reference". search.credoreference.com. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- 1 2 3 4 Leavitt, Henrietta S.; Pickering, Edward C. (1912). "Periods of 25 Variable Stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud" (PDF). Harvard College Observatory Circular. 173: 1–3. Bibcode:1912HarCi.173....1L.

- ↑ Gregory M. Lamb (July 5, 2005). "Before computers, there were these humans..." Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ↑ Byers, Nina, ed. (2006). Out of the Shadows: Contributions of Twentieth-century Women to Physics (Reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-521-82197-1.

- 1 2 3 "1912: Henrietta Leavitt Discovers the Distance Key." Everyday Cosmology. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2014. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Johnson, George (2005). Miss Leavitt's Stars : The Untold Story of the Woman Who Discovered How To Measure the Universe (1st ed.). New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-05128-5.

- ↑ Hockey, Thomas (2007). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer.

- ↑ Singh, S (2005). Big Bang. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-715252-0.

- ↑ Kidwell, Peggy Aldrich (2000). Leavitt, Henrietta Swan. American National Biography Online. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ "Origins: Hubble: People: Women In Astronomy - Exploratorium". Exploratorium: the museum of science, art and human perception.

- ↑ Sobel, Dava (2016). The Glass Universe. Viking. ISBN 978-0670016952.

- ↑ Jeremy Bernstein, "Review: George Johnson's Miss Leavitt's Stars", Los Angeles Times, July 17, 2005

- ↑ Leavitt, Henrietta S. (1908). "1777 variables in the Magellanic Clouds". Annals of Harvard College Observatory. 60: 87–108.3. Bibcode:1908AnHar..60...87L.

- 1 2 Hamblin, Jacob Darwin (2005). Science in the early twentieth century: an encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 181–184. ISBN 978-1-85109-665-7.

- ↑ Madore, Barry F.; Rigby, Jane; Freedman, Wendy L.; Persson, S. E.; Sturch, Laura; Mager, Violet (2009). "The Cepheid Period–Luminosity Relation (The Leavitt Law) at Mid-Infrared Wavelengths. III. Cepheids in NGC 6822". The Astrophysical Journal. 693 (1): 936–939. arXiv:0812.0186. Bibcode:2009ApJ...693..936M. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/693/1/936.

- ↑ Kerri Malatesta (16 July 2010). "Delta Cephei". American Association of Variable Star Observers.

- ↑ Henrietta Leavitt." Henrietta Leavitt. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2014. <http://www.sheisanastronomer.org/index.php/history/henrietta-leavitt>

- ↑ Fernie, J.D. (December 1969). "The Period–Luminosity Relation: A Historical Review". Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific. 81 (483): 707. Bibcode:1969PASP...81..707F. doi:10.1086/128847.

- ↑ Ventrudo, Brian (November 19, 2009). "Mile Markers to the Galaxies". One-Minute Astronomer. Retrieved April 7, 2013.

- ↑ Singh, Simon (2005). "Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe". New York: Fourth Estate. Bibcode:2004biba.book.....S. ISBN 978-0-00-716221-5.

- ↑ "Nomination FAQ". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ "Asteroids and Comets: 5383 Leavitt (4293 T-2) Leavitt Orbital Information". Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Moon Nomenclature". NASA. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2014-01-26.

- ↑ Measuring the Universe in 'Miss Leavitt's Stars'" NPR. NPR, n.d. Web. 20 Oct. 2014. <https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4738071>

- ↑ "Look Up!". simonandschuster.com. 19 February 2013.

Sources

- Johnson, George (2005). Miss Leavitt's Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05128-5.

- Korneck, Helena: "Frauen in der Astronomie", Sterne und Weltraum, Oct. 1982 412–414

- Lorenzen, Michael (1997). "Henrietta Swan Leavitt", in Notable Women in the Physical Sciences: A Biographical Dictionary. Edited by Barbara and Benjamin Shearer. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 233–237. ISBN 0-313-29303-1.

- Sobel, Dava (2016). The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars. Penguin. ISBN 9780670016952.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Henrietta Swan Leavitt |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Henrietta Swan Leavitt. |

- Bibliography from the Astronomical Society of the Pacific

- Periods of 25 Variable Stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud. Edward C. Pickering, March 3, 1912; credits Leavitt.

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt: a Star of the Brightest Magnitude ACS/Women Chemists Committee's biography with several links

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Tim Hunter (astronomer), The Grasslands Observatory

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt's genealogy

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt – Lady of Luminosity from the Woman Astronomer website