Henri de Tonti

Henri de Tonti (1649/50 – August 1704) was an Italian soldier, explorer, and fur trader in the service of France.[1]

Early life

Henri de Tonti, an Italian from the Kingdom of Naples, was most likely born near Gaeta, Italy, in either 1649 or 1650. He was the son of Lorenzo de Tonti, a financier and former governor of Gaeta. Alphonse de Tonti, one of the founders of what is now Detroit, was his younger brother.

His father, Lorenzo, was involved in a revolt against the Spanish viceroy in Naples, Italy, and was forced to seek political asylum in France around the time of Henri's birth.

In 1668, Henri joined the French Army and later served in the French Navy. During the Third Anglo-Dutch War, Henri was part of the French troops that King Louis XIV sent to Sicily in 1675 under the Command of The Duke of Vivonne to support the rebellion of the important town of Messina (circa 100.000 inhabitants in 1674) against the crown of Spain. Tonti took part in the military operations in the village of Gesso, up the hills near Messina and he lost his hand in a grenade explosion. From that time on, wore a prosthetic hook covered by a glove, thus earning the nickname "Iron Hand". Among the officers fighting beside the French expedition corps, there were the brothers Antonio and Thomas Crisafy, who years later Tonti will have the chance to meet again in Nouvelle France. [1]

Exploring with La Salle

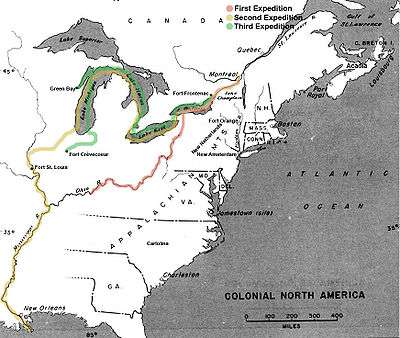

In the summer of 1678, Tonti journeyed with René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, who recognized him as an able associate. La Salle left Tonti to hold Fort Crèvecoeur in Illinois, while La Salle returned to Ontario. While on his return trip up the Illinois River, LaSalle concluded that Starved Rock might provide an ideal location for another fortification and sent word downriver to Tonti regarding this idea. Following La Salle’s instructions, Tonti took five men and departed up the river to evaluate the suitability of the Starved Rock site. Shortly after Tonti’s departure, on April 16, 1680, the seven members of the expedition who remained at Fort Crevecoeur ransacked and abandoned the fort and began their own march back to Canada.[2]

In the spring of 1682, Tonti journeyed with La Salle on his descent of the Mississippi River. Tonti's letters and journals are valuable source materials on these explorations.

When La Salle returned to France in 1683, he left Tonti behind to hold Fort Saint Louis on the Illinois River.[3] He was to relinquish this control for a period to Louis-Henri de Baugy, under the orders of Frontenac. Three years later, he learned from remnants of La Salle's ill-fated Texas settlement that La Salle was attempting to ascend the Mississippi River. De Tonti proceeded south on his own in an attempt to meet La Salle on his ascent. He failed to find La Salle and made it to the Gulf of Mexico before turning back. He left several men near the mouth of the Arkansas River to establish a trading post there on land granted to him by La Salle for his service. This location would become the historical Arkansas Post, the first permanent European settlement in the lower Mississippi region.[4]

Wars with English settlers

During 1687, Tonti was engaged in wars with the English and their Iroquois allies. In 1688, he returned to Fort Saint Louis and found members of La Salle's party who concealed the fact of La Salle's death. Tonti sent out parties to find survivors and then started out himself in October 1689.

Tonti travelled up the Red River and reached the Caddo villages in northeastern Texas in the spring of 1690. The Caddo offered him no assistance, and he was forced to withdraw.

Life in lower French Louisiana

Tonti experienced several financial difficulties in the 1690s, and in early 1700, he commenced a journey down the Mississippi to make contact with Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville,[1] who had established the Louisiana (New France) colony. Tonti reached French Louisiana and joined the colony.

In 1702, at Old Mobile, he was chosen by Iberville as an ambassador to the Choctaw and Chickasaw tribes and conducted several negotiations.[1] De Tonti, for whom the historic district north of present-day downtown Mobile is named, returned to the Old Mobile Site, with three Chickasaw chiefs and 2 Choctaw chiefs. The chiefs were rivals, but after Iberville had finished addressing them and presenting them gifts of guns and ammunition, they agreed to aid the settlers. The 22-year-old Bienville (a younger brother of Iberville) translated for Iberville.[5]

Tonti also led punitive expeditions from 1696 until 1704, with his cousin De Liette.

In August 1704 Tonti contracted yellow fever and died at Old Mobile, north of present-day Mobile, Alabama.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "A tour of Mobile's first 100 years", staff reporter, The Press-Register, Mobile, AL, 2002-02-24, webpage: MobReg-2.

- ↑ "Henri de Tonti, Founder of Peoria"

- ↑ Fort Saint Louis (Illinois) is distinct from the Fort Saint Louis founded in French colonization of Texas.

- ↑ Kathleen DuVal (February 6, 2013). "Arkansas Post". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved June 2013. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - ↑ Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism. "Henri de Tonti Historical Marker". Retrieved August 9, 2009.

See also

External links

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article about Henri de Tonti. |

- Tonti's Diplomatic Mission - Chickasaw.TV

- Osler, E. B. (1979) [1969]. "Tonty, Henri". In Hayne, David. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Handbook of Texas: Henri de Tonti

- Works by or about Henri de Tonti in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Biography in Jesuit Relations