Heidelberg School

The Heidelberg School was an Australian art movement of the late 19th century. The movement has latterly been described as Australian Impressionism.[1]

Melbourne art critic Sidney Dickinson coined the term in a July 1891 review of works by Arthur Streeton and Walter Withers. He noted that these and other local artists, who painted en plein air in Heidelberg on the city's outskirts, could be considered members of the "Heidelberg School". The term has since evolved to cover painters who worked together at "artists' camps" around Melbourne and Sydney in the 1880s and 1890s. Along with Streeton and Withers, Tom Roberts, Charles Conder and Frederick McCubbin are considered key figures of the movement. Drawing on naturalist and impressionist ideas, they sought to capture Australian life, the bush, and the harsh sunlight that typifies the country.

The works of these artists are notable, not only for their merits as compositions, but as part of Australia's cultural heritage. The period leading up to Federation in 1901 saw an upsurge in Australian nationalism, and is the setting for many classic stories of Australian folklore, made famous in the works of bush poets associated with the Bulletin School, such as Henry Lawson and Banjo Paterson. The Heidelberg School's work provides a visual complement to these tales and their images have become icons of Australian art. The artists are well-represented in Australia's major public galleries, including the National Gallery of Australia, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Art Gallery of New South Wales.

History

The name refers to the then rural area of Heidelberg east of Melbourne where practitioners of the style found their subject matter, though usage expanded to cover other Australian artists working in similar areas. The core group painted there on several occasions at "artist's camps" in the late 1880s and early 1890s. Besides Arthur Streeton and Walter Withers, other major artists in the movement included Tom Roberts, Frederick McCubbin and Charles Conder.[2] See below for a list of other associated artists.

9 by 5 Impression Exhibition

In August 1889, several artists of the Heidelberg School staged the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition at Buxton's Rooms, Swanston Street, opposite the Melbourne Town Hall. The exhibition's three principal artists were Charles Conder, Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, with minor contributions from Frederick McCubbin, National Gallery students R. E. Falls and Herbert Daly, and sculptor Charles Douglas Richardson, who exhibited five sculpted impressions. Most of the 183 works included in the exhibition were painted on wooden cigar-box panels, measuring 9 by 5 inches (23 × 13 cm), hence the name of the exhibition. Louis Abrahams, a member of the Box Hill artists' camp, scrounged most of the panels from his family's tobacconist shop. In order to emphasise the small size of the paintings, they were displayed in broad Red Gum frames, some left unornamented, others decorated with verse and small sketches, giving the works an "unconventional, avant garde look".[3] The Japonist décor featured Japanese screens, umbrellas, and vases with flowers that perfumed the gallery, while the influence of Whistler's Aestheticism was also evident in the harmony and "total effect" of the display.[4]

The artists wrote in the catalogue:

An effect is only momentary: so an impressionist tries to find his place. Two half-hours are never alike, and he who tries to paint a sunset on two successive evenings, must be more or less painting from memory. So, in these works, it has been the object of the artists to render faithfully, and thus obtain first records of effects widely differing, and often of very fleeting character.

The exhibition caused a stir in Melbourne with many prominent social, intellectual and political figures attending during its three-week run. The general public responded positively, and within two weeks of the exhibition's opening, most of the 9 by 5s had sold. The response from critics, however, was mixed. The most scathing review came from leading critic James Smith, who said the 9 by 5s were "destitute of all sense of the beautiful" and "whatever influence [the exhibition] was likely to exercise could scarcely be otherwise than misleading and pernicious."[5] The artists pasted up the review outside the entrance of the venue—attracting many more passing pedestrians—and responded with a letter to the Editor of Smith's newspaper, The Argus. Described as a manifesto, the letter defends freedom of choice in subject and technique, concluding:

It is better to give our own idea than to get a merely superficial effect, which is apt to be a repetition of what others have done before us, and may shelter us in a safe mediocrity, which, while it will not attract condemnation, could never help towards the development of what we believe will be a great school of painting in Australia.[6]

The 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition is now regarded as a landmark event in Australian art history.[7] Approximately one-third of the 9 by 5s are known to have survived, many of which are held in Australia's public collections, and have sold at auction for prices exceeding $1,000,000.

Charles Conder, Centennial Choir at Sorrento, 1889

Charles Conder, Centennial Choir at Sorrento, 1889_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) Charles Conder, Going Home, 1889

Charles Conder, Going Home, 1889 Tom Roberts, Saplings, 1889

Tom Roberts, Saplings, 1889 Tom Roberts, The Violin Lesson, 1889

Tom Roberts, The Violin Lesson, 1889 Arthur Streeton, Impression for Golden Summer, 1888

Arthur Streeton, Impression for Golden Summer, 1888 Arthur Streeton, The National Game, 1889

Arthur Streeton, The National Game, 1889

Grosvenor Chambers

Opened at 9 Collins Street in April 1888, Grosvenor Chambers, built "expressly for occupation by artists", quickly became the focal point of Melbourne's art scene, and an urban base from which members of the Heidelberg School could meet the booming city's demand for portraits. Tom Roberts, Jane Sutherland and Clara Southern were the first to occupy studios in the building, and were soon followed by Charles Conder and Louis Abrahams.[8]

Many of the artists decorated their studios in an 'Aesthetic' manner, showing the influence of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Roberts' use of eucalypts and golden wattle as floral decorations started a fad for gum leaves in the home.[8]

The presence of Roberts, Streeton and Conder at Grosvenor Chambers is reflected in the high number of urban views they included in the 9 by 5 Impression Exhibition.[8]

Sydney

Roberts first visited Sydney in 1887. There, he met the young Conder, and a strong artistic friendship blossomed. The pair painted together at the beachside suburb of Coogee in early 1888 before Conder joined Roberts on his return trip to Melbourne.

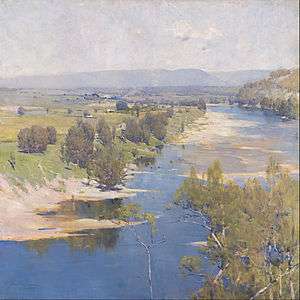

When a severe economic depression hit Melbourne in 1890, Roberts and Streeton moved to Sydney, first setting up camp at Mosman Bay, a small cove of the harbour, before finally settling around the corner at Curlew Camp, which was accessible by the Mosman ferry. Other plen air painters occasionally joined them at Curlew, including prominent art teacher and Heidelberg School supporter Julian Ashton, who resided nearby at the Balmoral artists' camp. Ashton had earlier painted with Conder during the latter's Sydney days, and in 1890, as a trustee of the National Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney, he encouraged the art museum to purchase Streeton's Heidelberg landscape ′Still glides the stream, and shall for ever glide′ (1890)—the first painting by the artist to enter a public gallery.[9] The more sympathetic patronage shown by Ashton and others in Sydney inspired other Melbourne artists to join them.

The National Gallery of Victoria notes:[10]

Sydney became Streeton's subject. The bravura of his crisp brushwork and his trademark blue, the blue that he had used at Heidelberg, were perfectly suited to registering images of the bustling activity on Sydney's blue harbour.

From Sydney, Streeton and Roberts branched out into country New South Wales, where, in the early 1890s, they painted some of their most celebrated works.

Influences and style

Like many of their contemporaries in Europe and North America, members of the Heidelberg School adopted a direct and impressionistic style of painting. They regularly painted landscapes en plein air, and sought to depict daily life. They showed a keen interest in the effects of lighting, and experimented with a variety of brushstroke techniques. Unlike the more radical approach of the French Impressionists, the Heidelberg School painters often maintained some degree of academic emphasis on form, clarity and composition. The latter group had little direct contact with the former; for example, it was not until 1907 that McCubbin saw their works in person, which is reflected in his evolution towards a looser, more abstracted style.

The Heidelberg School painters were not merely following an international trend, but "were interested in making paintings that looked distinctly Australian".[11] Works of the Heidelberg School are generally viewed as some of the first in Western art to realistically and sensitively depict the Australian landscape as it actually exists. The works of many earlier colonial artists look more like European scenes and do not reflect Australia's harsh sunlight, earthier colours and distinctive vegetation.

Associated artists

Artists associated with the Heidelberg School include:[2]

Locations

Legacy

Writing in 1980, Australian artist and scholar Ian Burn described the Heidelberg School as "mediating the relation to the bush of most people growing up in Australia. ... Perhaps no other local imagery is so much a part of an Australian consciousness and ideological make-up."[12] Their works are known to many Australians through reproductions, adorning stamps and paperback copies of colonial literature. Heidelberg School artworks are among the most collectible in Australian art; in 1995, the National Gallery of Australia acquired Streeton's Golden Summer, Eaglemont (1889) for $3.5 million, then a record price for an Australian painting.[13] The movement featured in the Australian citizenship test, overseen by former prime minister John Howard in 2007. Such references to history were removed the following year, instead focusing on "the commitments in the pledge rather than being a general knowledge quiz about Australia."[14]

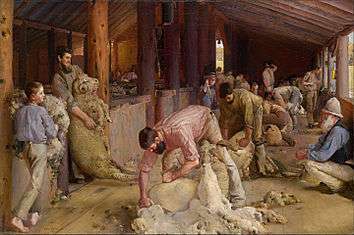

Many period films of the Australian New Wave drew upon the visual style and subject matter of the Heidelberg School.[15] For Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), director Peter Weir studied the Heidelberg School as a basis for art direction, lighting, and composition.[16] Sunday Too Far Away (1975), set on an outback sheep station, pays homage to Roberts' shearing works, to the extent that Shearing the Rams is recreated within the film. When shooting the landscape in The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), cinematographer Ian Baker tried to "make every shot a Tom Roberts".[17] The Getting of Wisdom (1977) and My Brilliant Career (1979) each found inspiration in the Heidelberg School;[15] outback scenes in the latter allude directly to works by Streeton, such as The Selector's Hut.[18]

The Heidelberg School is examined in One Summer Again, a three-part docudrama that first aired on ABC television in 1985.

The movement has been surveyed in major exhibitions, including the nationally touring Golden Summers: Heidelberg and Beyond (1986), and Australian Impressionism (2007), held at the National Gallery of Victoria.[19] The National Gallery in London hosted an exhibition titled Australia's Impressionists between December 2016 and March 2017, focusing on works by Streeton, Roberts, Conder and John Peter Russell, an Australian impressionist based in Europe.[20]

Gallery

Julian Ashton, Evening, Merri Creek, 1882

Julian Ashton, Evening, Merri Creek, 1882 Frederick McCubbin, The Letter, 1884

Frederick McCubbin, The Letter, 1884 Jane Sutherland, Obstruction, Box Hill, 1887

Jane Sutherland, Obstruction, Box Hill, 1887 Julian Ashton, The Corner of the Paddock, 1888

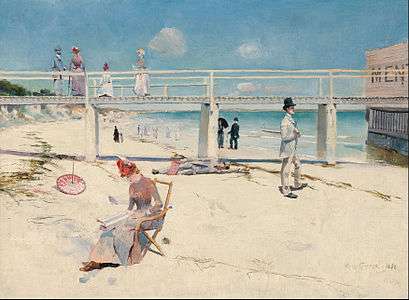

Julian Ashton, The Corner of the Paddock, 1888 Charles Conder, A holiday at Mentone, 1888

Charles Conder, A holiday at Mentone, 1888 Frederick McCubbin, Down on His Luck, 1889

Frederick McCubbin, Down on His Luck, 1889 Arthur Streeton, Golden Summer, Eaglemont, 1889

Arthur Streeton, Golden Summer, Eaglemont, 1889 Tom Roberts, Shearing the Rams, 1890

Tom Roberts, Shearing the Rams, 1890 Arthur Streeton, Fire's On, 1891

Arthur Streeton, Fire's On, 1891 Tom Roberts, A break away!, 1891

Tom Roberts, A break away!, 1891 Leon Pole, The Village Laundress, 1891

Leon Pole, The Village Laundress, 1891 Walter Withers, Panning for Gold, 1893

Walter Withers, Panning for Gold, 1893

See also

- John Peter Russell, Australian impressionist who spent much of his career in France

General:

References

- ↑ "Introduction to Australian Impressionism". Australian Impressionism. Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- 1 2 Heidelberg Artists Trail

- ↑ Lane, Australian Impressionism, p. 159

- ↑ Clark 1986, p. 114.

- ↑ Smith, James. "An Impressionist Exhibition". The Argus. 17 August 1889.

- ↑ Conder, Charles; Roberts, Tom; Streeton, Arthur. "Concerning 'Impressions' in Painting". The Argus. 3 September 1889.

- ↑ Moore, William (1934). The Story of Australian Art. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-14284-X. p. 74

- 1 2 3 Significant sites, National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ Galbally, Ann (1972). Arthur Streeton. Oxford University Press, p. 13.

- ↑ Australian Impressionism: Sites, National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Australian Impressionism: Education Resource, National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ Burn, Ian. "Beating About the Bush: The Landscapes of the Heidelberg School". In Bradley, Anthony; Smith, Terry. Australian Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0195505883, p. 83–98

- ↑ Strickland, Katrina. Affairs of the Art: Love, Loss and Power in the Art World. Melbourne University Publishing, 2013. ISBN 9780522864083.

- ↑ Anderson, Laura (22 November 2008). "Sporting focus taken off citizenship test", Herald Sun. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- 1 2 Gray, Anne (ed.) Australian Art in the National Gallery of Australia. Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2002. ISBN 0642541426, p. 12

- ↑ Rayner, Jonathan. The Films of Peter Weir. London: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2003. ISBN 0826419089, pp. 70–71

- ↑ Reynolds, Henry. The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith. Sydney: Currency Press, 2008. ISBN 0868198242, p. 66

- ↑ Elliot, Bonnie. "My Brilliant Career", World Cinema Directory. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- ↑ Grishin, Sasha (23 March 2016). "Tom Roberts at the National Gallery of Australia has gone gangbusters and here's why", Canberra Times. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- ↑ Collings, Matthew (6 December 2016). "Australia's Impressionists, exhibition review: A fascinating show on an explosive theme", Standard. Retrieved 18 May 2017.

Further reading

- Astbury, Leigh (1985). City Bushmen: The Heidelberg School and the Rural Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-554501-X.

- Astbury, Leigh (1989). Sunlight and Shadow: Australian Impressionist Painters 1880-1900. Bay Books. ISBN 1862562954.

- Caulfield, North (1988). The Australian Impressionists: Their Origins and Influences. Lauraine Diggins Fine Arts. ISBN 0959274340.

- Clark, Jane; Whitelaw, Bridget (1985). Golden Summers: Heidelberg and Beyond. International Cultural Corporation of Australia. ISBN 0642081824.

- Finlay, Eleanor; Morgan, Marjorie Jean (2007). Prelude to Heidelberg: The Artists' Camp at Box Hill. MM Publishing/City of Whitehorse. ISBN 0646484125.

- Gleeson, James (1976). Impressionist Painters, 1881-1930. Lansdowne Publishing. ISBN 0-7018-0990-6.

- Hammond, Victoria; Peers, Juliette (1992). Completing the Picture: Women Artists and the Heidelberg Era. Artmoves. ISBN 0-6460-7493-8.

- Lane, Terence (2007). Australian Impressionism. National Gallery of Victoria. ISBN 0-7241-0281-7.

- McCulloch, Alan (1977). The Golden Age of Australian Painting: Impressionism and the Heidelberg School. Lansdowne Publishing. ISBN 0-7018-0307-X.

- Splatt, William (1989). The Heidelberg School: The Golden Summer of Australian Painting. Viking O'Neil. ISBN 0-670-90061-3.

- Topliss, Helen (1984). The Artists' Camps: Plein Air Painting in Melbourne 1885-1898. Monash University Gallery. ISBN 0-8674-6326-0.

External resources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heidelberg School. |