Hans Globke

| Hans Globke | |

|---|---|

| |

| German Chancellery Chief of Staff | |

|

In office 28 October 1953 – 15 October 1963 | |

| Chancellor | Konrad Adenauer |

| Preceded by | Otto Lenz |

| Succeeded by | Ludger Westrick |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Hans Josef Maria Globke 10 September 1898 Düsseldorf, German Empire |

| Died | 13 February 1973 (aged 74) |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | CDU |

| Spouse(s) | Augusta Vaillant |

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician |

| Known for | Advisor to Konrad Adenauer |

Hans Josef Maria Globke (10 September 1898 – 13 February 1973) was a German lawyer, high-ranking civil servant and politician. During World War II, Globke, a Ministerialdirigent in the Office for Jewish Affairs in the Ministry of the Interior, wrote a legal annotation on the anti-semitic Nuremberg Race Laws that did not express any objection to the discrimination against Jews, and placed the Nazi Party on a firmer legal ground, setting the path to The Holocaust.[1] Globke later had a controversial career as Secretary of State and Chief of Staff of the German Chancellery in West Germany from 28 October 1953 to 15 October 1963. In this role he was responsible for running the Chancellery, recommending the people who were appointed to roles in the government, coordinating the government's work, and for the establishment and oversight of the West German intelligence service and for all matters of national security.[2]

Globke became a powerful éminence grise of the West German government; he had a major role in shaping the course and structure of the state and West Germany's alignment with the United States. He was also instrumental in West Germany's anti-communist policies at the domestic and international level and in the western intelligence community, as he was the German government's main liaison with NATO and other western intelligence services, especially the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and therefore protected. During his lifetime, his role in the National Socialist dictatorship was only partially known.

Early life and education

Globke was born in Düsseldorf, Rhine Province, the son of the cloth wholesaler Josef Globke and his wife Sophie (née Erberich), both Roman Catholics and supporters of the Centre Party.[2] Shortly after Hans's birth, the family moved to Aachen, where his father opened a draper's shop. When he finished his secondary education at the elite Catholic Kaiser-Karl-Gymnasium in 1916, he was drafted, serving until the end of World War I in an artillery unit on the Western Front. After World War I, he studied law and political science at the University of Bonn and the University of Cologne. In 1922 Globke qualified as a doctor of law (Dr. jur.) at the University of Giessen, with a dissertation on The immunity of the members of the Reichstag and the Landtag (German: Die Immunität der Mitglieder des Reichstages und der Landtage).

While studying Globke, a practising Catholic, joined the Bonn chapter of the Cartellverband (KdStV), the German Catholic Students' Federation. His close contacts with fellow KdStV members and his membership from 1922 in the Catholic Centre Party played a significant role in his later political life.

In 1934 he married Augusta Vaillant, with whom he had two sons and one daughter.[3]

Career pre-National Socialism

Globke finished his Assessorexamen in 1924 and briefly served as a judge in the police court of Aachen. He became vice police-chief of Aachen in 1925 and governmental civil servant with a rank of Regierungsassessor (District Assessor) in 1926. In December 1929, Globke entered the Higher Civil Service in the Prussian Ministry of the Interior, secured his final takeover in the Prussian civil service.

In November 1932, about two months before Hitler became chancellor, Globke wrote a set of rules to make it harder for Germans of Jewish ancestry in Prussia to change their last names to less obviously Jewish names, followed by guidelines for their implementation in December 1932. An excerpt stated:

Every name change makes it harder to determine family ties, true marital status and ancestry. Therefore the name can only be changed if an important reason exists.

This unequal treatment of the Jews in the final phase of the Weimar Republic, in which Globke played a major role, is considered by researchers and in the earlier case law of East Germany to be a precursor to name-related discrimination during the National Socialist era,[4] and a sign of Globke's anti-Semitic tendencies.[5]

Career during National Socialism

After the seizure of power by the Nazi Party in early 1933, Globke was involved in the drafting of a series of laws aimed at the co-ordination (German: Gleichschaltung) of the legal system of Prussia with the Reich. In December 1933, he was appointed to the upper government council, which Globke later said had been postponed due to his doubts over the legality of the so-called Prussian coup of 1932, which was well known in the Ministry. Globke helped to formulate the Enabling Act of 1933, which effectively gave Adolf Hitler dictatorial powers. He was also the author of the law of 10 July 1933 concerning the dissolution of the Prussian State Council and of further legislation that co-ordinated all Prussian parliamentary bodies.[6]

On 1 November 1934, following the unification of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior with the Reich Ministry of the Interior, Globke took a position as a speaker in the newly formed Reich and Prussian Ministry of the Interior under Reich Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick, where he worked until 1945. In 1938 Globke received his final promotion of the Nazi period, to the ministerial council.

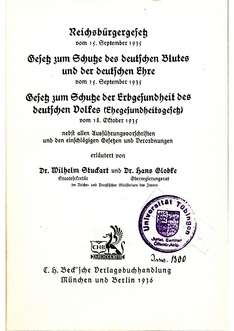

Measures to exclude and persecute Jews

From 1934 onwards, Globke continued to be responsible mainly for name changes and civil status issues; from 1937, international issues in the field of citizenship and option contracts were added to his brief. As a co-supervisor, he also dealt with "general race issues", immigration and emigration, and matters related to the anti-Semitic "racial shame" (German: Rassenschande) laws covering sexual relations between Aryans and non-Aryans. He co-authored the official legal commentary on the new Reich Citizenship Law, one of the Nuremberg Laws introduced at the Nazi Party Congress in September 1935, which revoked the citizenship of German Jews,[6][7] as well as various legal regulations, such as an ordinance that required Jews with non-Jewish names to take on the additional first names Israel or Sara, an "improvement" of public records that later facilitated to a great extent the rounding up and deportation of Jews during the Holocaust.[8] Globke's work also included the elaboration of templates and drafts for laws and ordinances. In this context, he had a leading role in the preparation of the first Ordinance on the Reich's civil law (enacted on 14 November 1935), The Law for the Defense of German Blood and Honor (enacted 18 October 1935), and the Civil Status Act (enacted on 3 November 1937). The "J" which was imprinted in the passports of Jews was designed by Globke.[9]

Globke also served as chief legal adviser to the Office for Jewish Affairs in the Ministry of Interior, headed by Adolf Eichmann, that performed the bureaucratic implementation of the Holocaust.[10]

In 1938, Globke was appointed Ministerialrat (Undersecretary) for his "extraordinary efforts in drafting the law for the Protection of the German Blood". On 25 April 1938, Globke was praised by the Reich Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick as "the most capable and efficient official in my ministry" when it came to drafting anti-Semitic laws.[11]

He applied for membership of the Nazi Party for career reasons in 1940, but the application was rejected on 24 October 1940 by Martin Bormann, reportedly because of his former membership of the Centre Party, which represented Roman Catholic voters in Weimar Germany.[12]

At the Nuremberg trials, he appeared at the Ministries Trial as a witness for both the prosecution and the defence. When questioned in the trial of his former superior Wilhelm Stuckart, he confirmed that he knew that "Jews were being put to death en masse".

During the war

At the beginning of the war, Globke was responsible for the new German imperial borders in the West that were the responsibility of the Reich Ministry of the Interior. He made several trips to the conquered territories. The historian Peter Schöttler suspected that Globke was probably the author of a memorandum to Hitler in June 1940 discussing the idea of State Secretary Wilhelm Stuckart proposing a far-reaching annexation of the East French and Belgian territories, which would have involved the deportation of about 5 million people.[13]

At the beginning of September 1941, Globke accompanied Interior Minister Frick and State Secretary Stuckart on an official visit to Slovakia, which at that time was a client state of the German Reich. Immediately following this visit, the government of Slovakia announced the introduction of the so-called Jewish Code, which provided the legal basis for the later expropriations and deportations of Slovak Jews. In 1961, Globke denied there was any connection between the two events and the allegation that he had participated in the creation of the Code. Clear evidence for it was never verified.[14] According to CIA documents, Globke was possibly also responsible for the deportation of 20,000 Jews from Northern Greece to Nazi extermination camps in Poland.[15][16]

Globke submitted a final application for Nazi Party membership, but the application was rejected in 1943, again due to his former affiliation to the Centre Party.[17]

On the other hand, Globke maintained contacts with military and civilian resistance groups. He was the informant of the Berlin Bishop Konrad von Preysing and had knowledge of the coup preparations by the opponents of Hitler Carl Friedrich Goerdeler and Ludwig Beck. According to reports by Jakob Kaiser and Otto Lenz, in the event that the attempt to overthrow the National Socialist regime had succeeded, Globke was earmarked for a senior ministerial post in an imperial government formed by Goerdeler. However, no evidence ever emerged to support Globke's later assertion that the National Socialists wanted to arrest him in 1945, but were prevented by the advance of the Allies.

Post-war period

During the process of denazification, Globke stated that he had been part of the resistance against National Socialism, and was therefore classified by the Arbitration Chamber on 8 September 1947 in Category V: Persons Exonerated.[18] Globke was a witness for both the defence and the prosecution at the Wilhelmstraße trial. At Stuckart's trial he testified as a witness for the defendant, "I knew that the Jews were mass murdered".[19]

Career in the Adenauer government

In the post-war era Globke rose to become one of the most powerful people in the German government. In 1949 he was appointed undersecretary at the German Chancellery. In 1951, he wrote a law that restored back pay, pensions, and advancement to civil servants who had served under the Nazi regime, including himself. John Le Carré wrote that these were "rights as they would have enjoyed if the Second World War hadn't taken place, or if Germany had won it. In a word, they would be entitled to whatever promotion would have come their way had their careers proceeded without the inconvenience of an Allied victory".[20] At the end of October 1953, following Otto Lenz's election to the Bundestag in the election of the previous month, Globke succeeded Lenz as Secretary of State at the Federal Chancellery, wielding a great deal of power behind the scenes and therefore an important pillar of Konrad Adenauer's "chancellor democracy" (German: Kanzlerdemokratie).

Globke served as Chief of Staff of the Chancellery from 1953 to 1963. As such he was one of the closest aides to Chancellor Adenauer, with significant influence over government policy. He advised Adenauer on political decisions during joint walks in the garden of the Chancellor's office, such as the reparations agreement with Israel. His areas of responsibility and his closeness to the Chancellor arguably made him one of the most powerful members of the government; he was responsible for running the Chancellery, recommending the people who were appointed to roles in the government, coordinating the government's work, for the establishment and oversight of the West German intelligence service and for all matters of national security.[2] He was the German government's main liaison with NATO and other western intelligence services, especially the CIA. He also maintained contact with the party apparatus and became "a kind of hidden secretary general" to the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), and contact with the Chancellor usually had to go through him.[21] As Adenauer and everyone else knew of his previous career, the Chancellor could be assured of his absolute loyalty.

Globke's key position as chief of staff to Adenauer, responsible for matters of national security, made both the West German government and CIA officials wary of exposing his past, despite their full knowledge of it. This led, for instance, to the withholding of Adolf Eichmann's alias from the Israeli government and Nazi hunters in the late 1950s, and CIA pressure in 1960 on Life magazine to delete references to Globke from its recently obtained Eichmann memoirs.[22][23][24]

Globke left office together with the Adenauer administration in 1963, and was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany by President Heinrich Lübke. He remained active as an adviser for Adenauer and the CDU during the 1960s. After retirement Globke decided to move to Switzerland. However, the Swiss government declared him an unwanted foreigner and denied him entry. Globke was buried in the central cemetery in Bad Godesberg in the district of Plittersdorf.

Globke's Nazi past

Political Debate

In a parliamentary debate on 12 July 1950, Adolf Arndt, the spokesman for the Social Democratic Party (SPD), read an excerpt from the commentaries on the Nuremberg Laws in which Globke discusses whether or not "racial shame" committed abroad could be punished. Federal Interior Minister Gustav Heinemann (then CDU) referred in his answer to the exonerating testimony of the Nuremberg prosecutor Robert Kempner, that Globke had served with his willingness to testify. Although Globke was controversial because of his Nazi past, Adenauer was loyal to Globke until the end of his term in 1963. On one hand, he commented on the debate over Globke's participation in the drafting of the Nuremberg race laws with the words "do not throw dirty water away, as long as you do not have clean" (German: Man schüttet kein schmutziges Wasser weg, solange man kein sauberes hat). On the other hand, he said in a newspaper interview on 25 March 1956 that claims Globke was a willing helper of the Nazis lacked any basis. Many people, including from the ranks of the Catholic Church, certified that Globke had repeatedly campaigned on behalf of persecuted people.[25]

However, loyalty to Globke increasingly proved to be a burden on Adenauer's government, especially after 1960, when the Israeli intelligence service Mossad tracked Adolf Eichmann down in Argentina.[26][27] Eichmann was living in Buenos Aires and working at Mercedes-Benz, and the German Federal Intelligence Service (BND) had been aware since 1952 that he lived there.

Whether or not Globke knew of Adolf Eichmann's whereabouts in Argentina at the end of the 1950s was still the subject of political debate in 2013.[28]

West German investigation

The former administrative officer of Army Group E in Thessaloniki, Max Merten, had accused Globke of being heavily responsible for the Holocaust in Greece, as he could have prevented the deaths of 20,000 Jews in Thessaloniki when Eichmann contacted the Reich Interior Ministry and asked for Globke's permission to kill them.[29] When these accusations became known, they prompted preliminary criminal proceedings to be initiated against Globke by Fritz Bauer, the chief public prosecutor of Hesse. The investigation was transferred to the public prosecutor's office in Bonn in May 1961 after an intervention by Adenauer, where it was closed due to lack of evidence.[29][30]

Trial in East Berlin

In the early 1960s, there was a vigorous campaign in East Germany, led by the Politburo member Albert Norden of the Ministry of State Security, against the so-called "author of the Nuremberg Blood Laws" as well as "Hetzer and organizer of the persecution of the Jews". Norden's goal was to prove that Globke was in contact with Eichmann. In a 1961 memorandum, Norden stated that "in collaboration with [Erich] Mielke, certain materials should be procured or produced. We definitely need a document that somehow proves Eichmann's direct cooperation with Globke".[31]

Globke became a central target of Soviet propaganda, not so much because of his career during the Nazi era, but because of his powerful position in the West German government and trenchant anti-communist stance. In 1963 East Germany convicted him in a show trial in absentia; however such East German trials were not recognised outside of the Soviet bloc, least of all by West Germany.[32] The fact that much of the criticism of Globke came from the Soviet bloc, and that it mixed genuine information with false accusations,[33] made it easier for the West Germans and the Americans to dismiss it as communist propaganda.

Scholarly investigation

In 1961, civil activist Reinhard Strecker wrote a book, Hans Globke - File Extracts, documents based on Strecker's research in Polish and Czech archives, which was published by the Bertelsmann publishing house Rütten & Loening.[34] Globke tried to block further publication in court with an interim injunction. The BND, under the leadership of the former Wehrmacht General Reinhard Gehlen, spent 50,000 marks trying to take the book off the market. When a court then discovered two minor mistakes (the publisher had caused one of them by abbreviation) and imposed a restraining order, Bertelsmann caved in, and cancelled a new edition of the book. The government is thought by historians to have threatened that no official agency would have acquired a book from the publisher again.[35]

In June 2006, it was announced that the Adenauer Government had informed the CIA of the location of Adolf Eichmann in March 1958. However, according to US historian Timothy Naftali, through contacts at the highest level, it had also ensured that the CIA did not use that knowledge. Neither the federal government nor the CIA passed the new information on to the Israeli government.[36][37][38][39] Naftali suggested that Adenauer had wanted to prevent pressure on Globke regarding Eichmann. Eichmann had previously given extensive interviews on his life to Dutch journalist and former SS agent Willem Sassen, on which his memoirs were to be based. Since 1957, Sassen's attempts to sell this material to US magazine Life had been unsuccessful. This changed with the spectacular kidnapping of Eichmann by Mossad in May 1960, made possible by an unofficial tip-off by the Hessian Attorney General Fritz Bauer, and the preparation of the Eichmann trial in Israel. Life published extracts from Sassen's material about Eichmann in two articles, on 28 November and 5 December 1960. His family wanted to use the royalties from the articles to fund his defence in court. However the federal government, already worried about the campaign in East Berlin, contacted the CIA to ensure that any material regarding Globke was removed from the Life coverage. In an internal memo dated 20 September 1960, CIA chief Allen Dulles mentioned "a vague mention of Globke, which Life omits at our demand".[40][41]

In 2009, a monograph by the historian Erik Lommatzsch was published by Campus-Verlag. Lommatzsch had investigated Globke's estate in the archive of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation.[42] However, Globke's actual relationship to National Socialism and his influence on the government of Adenauer are not really clarified, which, according to reviewer Hans-Heinrich Jansen, "in view of the sourcing, which for many central issues, turned out to be slim, after all" is not conclusively possible.[43] The background of the Stasi campaign against Globke remains largely unknown;[44] however, this aspect of Lommatzsch's biography was in any case only intended as a digression,[45] since it requires separate treatment. However, Lommatzsch mentions a number of examples of Globke campaigning for the persecuted, his commentary on the Nuremberg Laws was aimed at defusing the regulations, and he had not played the dominant role in the postwar period, the Adenauer opponents had assumed.[46]

The effects of the German-German system conflict on dealing with Nazi perpetrators under a pan-German perspective has only begun.[47][48]

Various federal agencies have already been scientifically investigated, with and without government support in relation to their Nazi past, for example the Federal Foreign Office. A research deficit in the processing of NS continuity in the Federal Republic of Germany still exists in particular at the German Chancellery.[49][50] A subsidy program worth a total of 4 million euros was included in the 2017 federal budget, which is intended to process the Nazi past of central authorities, especially the federal ministries, across departments.[51] The concrete conceptual and content-related design of the research program is currently being discussed by the Federal Commissioner for Culture and the Media, the Federal Archives and representatives of science[52] for example a collective biography of all state secretaries, in which Globke would be "only one of many"[53]

Honours and awards

Before 1945

- Honor Cross for Front Fighters (1934)[54]

- Medal commemorating the 13th of March 1938 (1938)

- Sudetenland Medal (1939)

- Silver Loyalty Merit Sign (1941)[55]

- War Merit Cross 2nd Class (1942)

- Commander's Cross of the Order of the Star of Romania (1942)[56]

After 1945

- Grand Decoration of Honour in Gold with Sash for Services to the Republic of Austria (1956)[57]

- Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic (1956)

- Grand Cross of the Order of the Oak Crown of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg (1957)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Christ of Portugal (1960)

- Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany (1963)

Works

- Globke, Hans (1922). Die Immunität der Mitglieder des Reichstages und der Landtage. Gießen, Germany: n/a.

- Stuckart, Wilhelm; Hans Globke (1936). Kommentar zur deutschen Rassengesetzgebung. Munich, Germany: n/a.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hans Globke. |

Bibliography

- Teitelbaum, Raul. Hans Globke and the Eichmann Trial: A Memoir, Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, Vol. V, No. 2 (2011)

- Tetens, T.H. The New Germany and the Old Nazis. Random House/Marzani & Munsel, New York, 1961. LCN 61-7240.

References

- ↑ Klaus, Wiegrefe (15 April 2011). "West Germany's Efforts to Influence the Eichmann Trial". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- 1 2 3 Bernard A. Cook (2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 513. ISBN 978-0-8153-4057-7. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ↑ Wirtz, Susanne. "Biography Hans Globke". LeMO biographies, Living Museum Online. Foundation House of History of the Federal Republic of Germany. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ RÜTER, C. F.; DE MILDT, D.W.; GOMBERT, L. HEKELAAR. "Verdict of the OG of the GDR on the case Globke" (PDF). University of Amsterdam. K.G. Saur Verlag. Archived from the original (pdf) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- ↑ Wagner-Kern, Michael (December 2002). Staat und Namensänderung : die öffentlich-rechtliche Namensänderung in Deutschland im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert [State and name change. The change of public name in Germany in the 19th and 20th century] (pdf). Tübingen: Mohr Siebrek Ek. ISBN 978-3-16-147718-8. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- 1 2 Wistrich, Robert (2002). Who's Who in Nazi Germany. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-26038-8.

- ↑ Bartosz Wieliński (2006). "CIA kryła Eichmanna". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish) (8 June 2006). Retrieved 2006-06-08.

- ↑ Germany, SPIEGEL ONLINE, Hamburg. "A Triumph of Justice: On the Trail of Holocaust Organizer Adolf Eichmann".

- ↑ Vgl. Strecker (Hrsg.): Dr. Hans Globke. Aktenauszüge, Dokumente. Hamburg 1961, S. 144 ff.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ↑ Tetens, T.H. The New Germany and the Old Nazis, New York: Random House, 1961 page 39.

- ↑ Norbert Jacobs (1992). "Der Streit um Dr. Hans Globke in der öffentlichen Meinung der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1949–1973".

- ↑ Schöttler, Peter (2003). "A kind of "General plan West": The Stuckart memorandum of 14 June 1940 and the plans for a new Franco-German border during the Second World War". Social History. NF 18 (3): 88, 92 f. and 106.

- ↑ Bevers, Jürgen (April 2009). The man behind Adenauer Hans Globkes ascent from Nazi lawyer to the grey eminence of the Bonn Republic Der Mann hinter Adenauer Hans Globkes Aufstieg vom NS-Juristen zur Grauen Eminenz der Bonner Republik (in German). Berlin: Verlag GmbH. pp. S. 44 f. ISBN 978-3-86153-518-8. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ "E EICHMANN TRIAL" (pdf). Central Intelligence Agency. 6 April 1961. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ↑ Wolfgang Breyer (2003). "Dr. Max Merten - a military official of the German Wehrmacht in the field of tension between legend and truth, German: Dr. Max Merten – ein Militärbeamter der deutschen Wehrmacht im Spannungsfeld zwischen Legende und Wahrheit" (PDF). Inauguraldissertation. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ Ernst Klee: Das Personenlexikon zum Dritten Reich. Wer war was vor und nach 1945. 2. Auflage. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, S. 187.

- ↑ Lommatzsch., Erik (14 September 2009). Hans Globke (1898-1973) Beamter im Dritten Reich und Staatssekretär Adenauers (PDF). http://www.campus.de/uploads/tx_saltbookproduct/press_text/9783593390352.pdf: Campus Verlag GmbH. pp. S. 108–111. ISBN 978-3-593-39035-2. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ The judgment in the Wilhelmstrasse process. P. 167.

- ↑ Le Carré, John, The Pigeon Tunnel, Viking Press, 2016, pg. 26

- ↑ Daniel E. Rogers, "Restoring a German Career, 1945–1950: The Ambiguity of Being Hans Globke," German Studies Review, Vol. 31, No. 2 (May, 2008), pp. 303–324

- ↑ Yen, Hope (6 June 2006). "Papers: CIA knew of Eichmann whereabouts". Associated Press. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Shane, Scott (6 June 2006). "Documents Shed Light on CIA's Use of Ex-Nazis". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Weber, Gaby (4 March 2011). "Die Entführungslegende oder: Wie kam Eichmann nach Jerusalem?". Deutschlandradio. Retrieved 2011-03-05.

- ↑ Chronik 1956. Chronik Verlag im Bertelsmann Lexikon Verlag, 1989, 1996 C, S. 58.

- ↑ Klaus Wiegrefe: Der Fluch der bösen Tat. Die Angst vor Adolf Eichmann. Der Spiegel, 11. April 2011

- ↑ Willi Winkler: Holocaust-Prozess: Adolf Eichmann. Als Adenauer in Panik geriet Süddeutsche Zeitung, 29. März 2011

- ↑ Aufklärung über die Beziehungen von Bundesregierung und Bundesnachrichtendienst zu Adolf Eichmann Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage der Abgeordneten Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Ekin Deligöz, Katja Dörner, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN. BT-Drucksache 17/13563 vom 13. Mai 2013. pdf. Abgerufen am 16. September 2016.

- 1 2 Genocidium - Der Fall Globke, Fritz Bauer Archiv, abgerufen am 15. September 2016

- ↑ Jürgen Bevers: Der Mann hinter Adenauer. Hans Globkes Aufstieg vom NS-Jursiten zur Grauen Eminenz der Bonner Republik. Berlin: Christoph Links Verlag 2009, S. 170 f.

- ↑ Zitiert nach: Michael Lemke: Kampagnen gegen Bonn: Die Systemkrise der DDR und die Westpropaganda der SED 1960–1963. In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte. Band 41, 1993, S. 153–174, hier S. 163.

- ↑ "Poslanecká sněmovna Parlamentu České republiky, Čtvrtek 24. září 1964" (in Czech). Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 21 September 2013.

- ↑ Germany. "The Holocaust in the Dock: West Germany's Efforts to Influence the Eichmann Trial". Der Spiegel.

- ↑ Reinhard-M. Strecker (Hrsg.): Dr. Hans Globke. Aktenauszüge, Dokumente. Rütten & Loening, Hamburg 1961 (dnb)

- ↑ Otto, Köhler (16 June 2006). "Eichmann, Globke, Adenauer - CIA File Findings Why the right hand of the Federal Chancellor had to be spared". der Freitag Mediengesellschaft. der Freitag Mediengesellschaft mbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ↑ Timothy, Naftali (6 June 2006). "New Information on Cold War CIA Stay-Behind Operations in Germany and on the Adolf Eichmann Case S. 4 ff" (pdf). Federation of American Scientists. University of Virginia. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ↑ Scott, Shane (7 June 2006). "C.I.A. Knew Where Eichmann Was Hiding, Documents Show". New York Times. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ↑ Jennifer, Abramsohn (10 June 2006). "This is German history". Deutsche Welle Politik (in German). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ↑ Kleine-Brockhoff, Von Riedl (13 June 2006). "Among friends German:Unter Freunden" (in German). Nr. 25/2006: Die Zeit. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ↑ Timothy, Naftali (6 June 2006). "New Information on Cold War CIA Stay-Behind Operations in Germany and on the Adolf Eichmann Case S. 6 u. 16" (pdf). Federation of American Scientists. University of Virginia. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ↑ Blasius, von Rainer (7 June 2006). "National Socialism: Nazi criminals covered, Secretary of State protected, German:Nationalsozialismus: Nazi-Verbrecher gedeckt, Staatssekretär geschützt" (in German). Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ↑ Lommatzsch, Erik (2009). Hans Globke (1898-1973) Official in the Third Reich and State Secretary Adenauer German:Beamter im Dritten Reich und Staatssekretär Adenauers. Frankfurt am Main/New York: Campus Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-593-39035-2.

- ↑ "E. Lommatzsch: Hans Globke". H-Soz-Kult. Department of History at the Humboldt University in Berlin. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (1 October 2009). "Symbol of the early Federal Republic German:Symbolfigur der frühen Bundesrepublik on Hitler zu Adenauer – Eine neue Biografie zeichnet ein differenzierteres Bild von Hans Globke". Die Welt (in German). Axel Springer SE. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Lommatzsch, Erik (2009). Hans Globke (1898-1973) Official in the Third Reich and State Secretary Adenauer German:Beamter im Dritten Reich und Staatssekretär Adenauers. S. 310-322. Frankfurt am Main/New York: Campus Verlag GmbH. ISBN 978-3-593-39035-2.

- ↑ Lommatzsch, Erik. "Hans Globke and National Socialism. A sketch German:Hans Globke und der Nationalsozialismus. Eine Skizze" (pdf). Konrad Adenauer Foundation. Germany: Konrad Adenauer Foundation , 2018. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Weinke, Annette (4 August 2004). "The Persecution of Nazi Perpetrators in Divided Germany [Review]". Review Journal of History, German:Sehepunkte. Rezensions journal für die Geschichtswissenschaften (in German). 3 (4). Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Wentker, Hermann (2002). "The legal sanction of Nazi crimes in the Soviet occupation German:zone and in the GDRDie juristische Ahndung von NS-Verbrechen in der Sowjetischen Besatzungszone und in der DDR S. 60-78" (pdf). Critical justice de:Kritische Justiz (in German). 2018 Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft ^. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ↑ Mentel, Christian; Weise, Niels. "Central German Authorities and National Socialism - Status and Perspectives of Research German:Die zentralen deutschen Behörden und der Nationalsozialismus – Stand und Perspektiven der Forschung" (pdf). Institut für Zeitgeschichte (in German). Institute for Contemporary History Munich 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ Maisch, Andreas (16 March 2015). "The Chancellor's Office Wraps Up the Nazi Review German:Das Kanzleramt verschludert die NS-Aufarbeitung". Die Welt. Die Welt. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "Grütters: Significantly higher support for cultural institutions and federal projects for 2017 reached, German: Grütters: Deutlich höhere Förderung kultureller Institutionen und Projekte des Bundes für 2017 erreich". Der Bundesregierung (in German). 2018 Press and Information Office of the Federal Government. 6 July 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "Response of the Federal Government to the Small Question on the Federal Government's Plans to Investigate the History of the Federal Chancellery German:Antwort der Bundesregierung auf die Kleine Anfrage zu den Plänen der Bundesregierung zur Untersuchung der Geschichte des Bundeskanzleramtes" (pdf). Sigrid Hupach. German Federal Government. 23 August 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ "Chancellery has its Nazi past investigated". SPIEGELnet GmbH. Der Speigel. 30 April 2016. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ↑ Oberstes Gericht der DDR, Urteil vom 23. Juli 1963, Az.: 1 Zst (I) 1/63 – auf eigenen Antrag. Prof. Dr. C.F. Rüter: DDR-Justiz und NS-Verbrechen, Bd.III, Verfahren NR.1068.

- ↑ für 25-jährige Beamtentätigkeit unter Anrechnung des Militärdienstes

- ↑ verliehen von der Antonescu-Regierung

- ↑ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (pdf) (in German). p. 26. Retrieved 2 October 2012.