Hanno the Navigator

| Hanno the Navigator | |

|---|---|

| Born | 5th or 6th century BC |

| Nationality | Carthaginian |

| Occupation | Navigator |

| Known for | Naval exploration of the western coast of Africa |

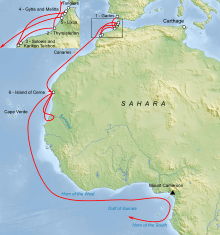

Hanno the Navigator[1] was a Carthaginian explorer of the sixth or fifth century BC,[2] best known for his supposed naval exploration of the western coast of Africa. The only source of his voyage is a Greek periplus. According to some modern analyses of his route, Hanno's expedition could have reached as far south as Gabon, however, others have taken him no further than southern Morocco.

Expedition

Carthage dispatched Hanno at the head of a fleet of 60 ships to explore and colonize the northwestern coast of Africa.[3] He sailed through the straits of Gibraltar, founded or repopulated seven colonies along the African coast of what is now Morocco, and explored significantly farther along the Atlantic coast of the continent. Hanno encountered various indigenous peoples on his journey and met with a variety of welcomes.

Gorillai

At the terminus of Hanno's voyage, the explorer found an island heavily populated with what were described as hirsute and savage people. Attempts to capture the males failed, but three of the females were taken. These were so ferocious that they were killed, and their skins preserved for transport home to Carthage. The skins were kept in the Temple of Juno (Tanit or Astarte) on Hanno's return and, according to Pliny the Elder, survived until the Roman destruction of Carthage in 146 BC, some 350 years after Hanno's expedition.[4][5] The interpreters travelling with Hanno called the people Gorillai (in the Greek text Γόριλλαι). When the American physician and missionary Thomas Staughton Savage and naturalist Jeffries Wyman first described the gorillas in the 19th century, the apes were named Troglodytes gorilla after the description in Hanno.[6][7]

In its inmost recess was an island similar to that formerly described, which contained in like manner a lake with another island, inhabited by a rude description of people. The females were much more numerous than the males, and had rough skins: our interpreters called them Gorillae. We pursued but could take none of the males; they all escaped to the top of precipices, which they mounted with ease, and threw down stones; we took three of the females, but they made such violent struggles, biting and tearing their captors, that we killed them, and stripped off the skins, which we carried to Carthage: being out of provisions we could go no further.

— The periplus Hanno, [8]

Periplus account

The primary source for Hanno's expedition is a Greek periplus, supposedly a translation of a tablet Hanno is reported to have hung up on his return to Carthage in the temple of Ba'al Hammon, whom Greek writers identified with Kronos. The full title translated from Greek is The Voyage of Hanno, commander of the Carthaginians, round the parts of Libya beyond the Pillars of Heracles, which he deposited in the Temple of Kronos.

In the fifth century, the text was translated into a rather mediocre Greek. It was not a complete rendering; several abridgments were made. The abridged translation was copied several times by Greek and Byzantine clerks. Currently, there are only two copies, dating back to the ninth and the fourteenth centuries.[4]

The first of these manuscripts is known as the Palatinus Graecus 398 and can be studied in the University Library of Heidelberg.[9] The other text is in the Codex Vatopedinus 655, found in the Vatopedi monastery in Mount Athos, Greece, and dated to the beginning of the 14th century; the codex is divided between the British Library[10] and the French Bibliothèque Nationale.[4][11]

Ancient authors' accounts

The text was known to Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, and Arrian of Nicomedia.

Herodotus' account

The Greek historian Herodotus (ca.480–425 BC) gives a story based probably upon Hanno's original report.

The Carthaginians tell us that they trade with a race of men who live in a part of Libya beyond the Pillars of Herakles. On reaching this country, they unload their goods, arrange them tidily along the beach, and then, returning to their boats, raise a smoke. Seeing the smoke, the natives come down to the beach, place on the ground a certain quantity of gold in exchange for the goods, and go off again to a distance. The Carthaginians then come ashore and take a look at the gold; and if they think it presents a fair price for their wares, they collect it and go away; if, on the other hand, it seems too little, they go back aboard and wait, and the natives come and add to the gold until they are satisfied. There is perfect honesty on both sides; the Carthaginians never touch the gold until it equals in value what they have offered for sale, and the natives never touch the goods until the gold has been taken away.

— Herodotus of Halicarnassus, [12]

Pliny the Elder's account

According to Pliny the Elder, Hanno started his journey at the same time that Himilco started to explore the European Atlantic coast. Pliny reports that Hanno actually managed to circumnavigate the African continent, from Gades to Arabia.[13]

Arrian's account

Arrian mentions Hanno's voyage at the end of his Anabasis of Alexander VIII (Indica):

Moreover, Hanno the Libyan started out from Carthage and passed the Pillars of Heracles and sailed into the outer Ocean, with Libya on his port side, and he sailed on towards the east, five-and-thirty days all told. But when at last he turned southward, he fell in with every sort of difficulty, want of water, blazing heat, and fiery streams running into the sea.

— Arrian of Nicomedia, [14]

Modern analysis of the route

A number of modern scholars have commented upon Hanno's voyage. In many cases, the analysis has been to refine information and interpretation of the original account. William Smith points out that the complement of personnel totalled 30,000, and that the core mission included the intent to found Carthaginian (or in the older parlance 'Libyophoenician') towns. [15] Some scholars have questioned whether this many people accompanied Hanno on his expedition, and suggest 5,000 is a more accurate number.[4] Robin Law notes that "It is a measure of the obscurity of the problem that while some commentators have argued that Hanno reached the Gabon area, others have taken him no further than southern Morocco."[16]

Harden reports a general consensus that the expedition reached at least as far as Senegal.[17] Some agree he could have reached Gambia. However, Harden mentions disagreement as to the farthest limit of Hanno's explorations: Sierra Leone, Cameroon, or Gabon. He notes the description of Mount Cameroon, a 4,040-metre (13,250 ft) volcano, more closely matches Hanno's description than Guinea's 890-metre (2,920 ft) Mount Kakulima. Warmington prefers Mount Kakulima, considering Mount Cameroon too distant.[18]

Warmington suggests[19] that difficulties in reconciling the account's specific details with present geographical understanding are consistent with classical reports of Carthaginian determination to maintain sole control of trade into the Atlantic.

This report was the object of criticism by some ancient writers, including the Pliny the Elder, and in modern times a whole literature of scholarship has grown up around it. The account is incoherent and at times certainly incorrect, and attempts to identify the various places mentioned on the basis of the sailing directions and distances almost all fail. Some scholars resort to textual emendations, justified in some cases; but it is probable that what we have before us is a report deliberately edited so that the places could not be identified by the competitors of Carthage. From everything we know about Carthaginian practice, the resolute determination to keep all knowledge of and access to the western markets from the Greeks, it is incredible that they would have allowed the publication of an accurate description of the voyage for all to read. What we have is an official version of the real report made by Hanno which conceals or falsifies vital information while at the same time gratifying the pride of the Carthaginians in their achievements. The very purpose of the voyage, the consolidation of the route to the gold market, is not even mentioned.

The historian Raymond Mauny, in his 1955 article La navigation sur les côtes du Sahara pendant l'antiquité, argued that the ancient navigators (Hannon, Euthymène, Scylax, etc ..) could not have sailed south in the Atlantic farther than Cape Bojador. He pointed out that antique geographers knew of the Canary Islands but nothing further south. Ships with square sails, without stern rudder, might navigate south, but the winds and currents throughout the year would prevent the return trip from Senegal to Morocco. Oared ships might be able to achieve the return northward, but only with very great difficulties. Mauny assumed that Hanno did not get farther than the Drâa. He attributed artifacts found on Mogador island to the expedition described in the Periplus of Pseudo-Scylax and notes that no evidence of Mediterranean trade further south had yet been found. The author ends by suggesting archaeological investigation of the islands along the coast, such as Cape Verde, or the île de Herné (Dragon Island near Dakhla, Western Sahara) where ancient adventurers may have been stranded and settled.[20]

Popular culture

- The lunar crater Hanno is named after him.[21]

- Hanno was a subject of the second episode of the History Channel documentary Mankind: The Story of All of Us.

- Hanno is the subject of the song "Hanno the Navigator" by Al Stewart from his album Sparks of Ancient Light.

See also

Notes

- ↑ This Hanno is called the Navigator to distinguish him from a number of other Carthaginians with this name, including the perhaps more prominent, though later, Hanno the Great (see Hanno for others of this name). The name Hanno (Annôn) means "merciful" or "mild" in Punic.

- ↑ Fage, J. D.; Roland, Anthony Oliver; Roberts, A. D., eds. (1979). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3.

- ↑ Warmington 1964, pp. 74–76.

- 1 2 3 4 Jona Lendering. "Hanno the Navigator". Livius.org Articles on Ancient History. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ Hoyos, Dexter (2010), The Carthaginians, Routledge, p. 53, ISBN 978-0415436458

- ↑ Savage TS. (1847). Communication describing the external character and habits of a new species of Troglodytes (T. gorilla). Boston Soc Nat Hist: 245–247.

- ↑ Savage TS, Wyman J. (1847). Notice of the external characters and habits of Troglodytes gorilla, a new species of orang from the Gaboon River, osteology of the same. Boston J Nat Hist 5:417–443.

- ↑ Murray, Hugh (1844), An Encyclopaedia of Geography, Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans, pp. 11–12

- ↑ "Codex Palatinus Graecus 398". Heidelberger historische Bestände. University Library Heidelberg. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ British Library. Add. MS 19391.

- ↑ Bibliothèque Nationale. Suppl. gr. 443 (Pithou MS).

- ↑ Herodotus. "Histories 4.196". Livius.org. translation Aubrey de Selincourt. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 2.169.

- ↑ Arrian; P. A. Brunt; I. Robson (1978). Arrian: Books 5–7 Anabasis Alexandri, Book 8 Indica. Harvard University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-434-99269-0. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Smith, William (2005) [First published 1870]. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. 2. The Ancient Library. p. 346. Archived from the original on October 26, 2005. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ R.C.C. Law (1979). "North Africa in the period of Phoenician and greek colonization". In Fage, J.D. The Cambridge History of Africa, Volume 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 9780521215923. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Harden 1971, p. 168.

- ↑ Warmington 1964, pp. 79.

- ↑ Warmington 1964, p. 76.

- ↑ Mauny, Raymond (1955). "La navigation sur les côtes du Sahara pendant l'antiquité". Revue des Études Anciennes (in French). 57 (1): 92–101. doi:10.3406/rea.1955.3523.

- ↑ "Planetary Names: Crater, craters: Hanno on Moon". Retrieved June 6, 2011.

Sources

- Warmington, Brian H. (1964) [First published 1960]. Carthage. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Harden, Donald (1971) [First published 1962]. The Phoenicians. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Herodotus, transl. Aubrey de Selincourt, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1968 (1954)

Further reading

- Bunbury, Edward Herbert (1879). A History of Ancient Geography Among the Greeks and Romans, from the Earliest Ages till the Fall of the Roman Empire. London: Murray.

- Carpenter, Rhys (1966). Beyond the Pillars of Heracles. New York: Delacorte Press.

- Cary, Max; Warmington, E.H. (1963). The Ancient Explorers. Baltimore: Penguin Books.

- Hyde, Walter Woodburn (1947). Ancient Greek Mariners. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kaeppel, Carl (1936). Off the Beaten Track in the Classics. New York: Melbourne University Press.

- Oikonomides, Al. N.; M.C.J. Miller (1995). Periplus or Circumnavigation (of Africa) (3rd ed.). Chicago: Ares Publishers. ISBN 0-89005-180-1.

- Thomson, J.O. (1965). History of Ancient Geography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Works by Hanno the Navigator at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Arriani et Hannonis periplus. Plutarchus de fluminibus et montibus. Strabonis epitome, Basilea, Froben, 1533.

- Primo volume delle navigationi et viaggi nel qual si contiene la descrittione dell'Africa, Venecia, Giunti, 1550, pp. 121-124.

- Hannonis periplus. Quem a se latine conversum et annotatione quadam auctum in Inclyta Academia Argentoratensi, Joannes Jacob Mueller (ed.), Estrasburgo, J. Staedel, 1661.

- Genuina Stephani Byzantini de urbibus et populis fragmenta, accedit Hannonis carthaginensium regis periplus, A. Berkelius (ed.), Leyden, D. Van Gaestbeeck, 1674.

- Geographi graeci minores, Karl Otfried Müller, Paris, editoribus Firmin-Didot et sociis, 1882, vol. 1 pp. 1-14.

- The Periplus of Hanno : a voyage of discovery down the west African coast, by a Carthaginian admiral of the fifth century B.C. / the Greek text, with a translation by Wilfred H. Schoff ; with explanatory passages quoted from numerous authors. Philadelphia : Commercial Museum, 1913

- "Hanno's Periplus on the Web:" a directory of further links.

- Livio Catullo Stecchini, "The voyage of Hanno" carefully analyzed by a classical scholar

- Periplus in English.

- Hanno's Voyage from Canaanite.org

- Hanno, a Carthaginian navigator from Charles Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology (1867)

- Annotated commentary on Hanno's Periplus by Jona Lendering

- Scan of an original Byzantine manuscript on "Hanno Carthagiensis"