Grind

A blade's grind is its cross-sectional shape in a plane normal to the edge. Grind differs from blade profile, which is the blade's cross-sectional shape in the plane containing the blade's edge and the centre contour of the blade's back.

Grinding is the process of creating grinds. It involves removing significant portions of material from a blade, which distinguishes it from honing and polishing. Blades are ground during their initial sharpening or after having been sufficiently damaged, such as by breaking a tip, chipping, or extensive corrosion. Well-maintained blades need grinding less frequently than neglected or maltreated ones do.

Edge angle and included angle typically characterize a blade's grind. An edge angle is measured between a line lying in the plane of one of the edge's faces and a second line intersecting the back's centre contour, both lines lying in the same plane normal to the edge. The included angle is the sum of the edge angles. Ceteris paribus, the smaller the included angle, the sharper the blade and the more easily damaged its edge.

An appropriate grind depends upon a blade's intended use and the material composing it. Knife manufacturers may offer the same blade with different grinds and blade owners may choose to regrind their blades to obtain different properties. A trade-off exists between a blade's ability to take an edge and its ability to keep one. Some grinds are easier to maintain than others, better retaining their integrity as repeated sharpening wears away the blade. Harder steels take sharper edges, but are more brittle and hence chip more easily, whereas softer steels are tougher. The latter are used for knives such as cleavers, which must be tough but do not require a sharp edge. In the range of blade materials' hardnesses, the relationship between hardness and toughness is fairly complex and great hardness and great toughness are often possible simultaneously.

As a rough guide, Western kitchen knives are generally double-bevelled (about 15° on the first bevel and 20°–22° on the second), whereas East Asian kitchen knives, made of harder steel and being either wedge- (double-ground) or chisel-shaped (single-ground), are ground to 15°–18°.

Process

A sharp object works by concentrating forces which creates a high pressure due to the very small area of the edge, but high pressures can nick a thin blade or even cause it to roll over into a rounded tube when it is used against hard materials. An irregular material or angled cut is also likely to apply much more torque to hollow-ground blades due to the "lip" formed on either side of the edge. More blade material can be included directly behind the cutting edge to reinforce it, but during sharpening some proportion of this material must be removed to reshape the edge, making the process more time-consuming. Also, any object being cut must be moved aside to make way for this wider blade section, and any force distributed to the grind surface reduces the pressure applied at the edge.[1]

One way around this dilemma is to use the blade at an angle, which can make a blade's grind seem less steep, much as a switchback makes a trail easier to climb. Using the edge in this way is made easier by introducing a curve in the blade, as seen in sabers, tulwars, shamshirs, and katanas, among many others. Some old European swords (most memorably Hrunting) and the Indonesian style of kris have a wavelike shape, with much the same effect in drawing or thrusting cuts.

When speaking of Japanese edged weapons, the term niku (肉 meat) refers to the grind of the blade: an edge with more niku is more convex and/or steep and therefore tougher, though it seems less sharp. Katana tend to have much more niku than wakizashi.

If it is required to measure the angles of cutting edges, it is achieved by using a blade edge protractor (or goniometer) see CATRA Hobbigoni

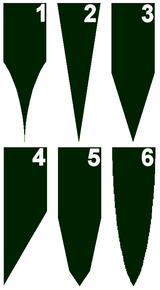

Typical grinds

- Hollow grind — a knife blade which has been ground to create a characteristic concave, beveled cutting edge. This is characteristic of straight razors, used for shaving, and yields a very sharp but weak edge which requires stropping for maintenance.

- Flat grind — The blade tapers all the way from the spine to the edge from both sides. A lot of metal is removed from the blade and is thus more difficult to grind, one factor that limits its commercial use. It sacrifices edge durability in favor of more sharpness. A true, flat ground knife having only a single bevel is somewhat of a rarity.

- Sabre grind — Similar to a flat grind blade except that the bevel starts at about the middle of the blade, not the spine. Also sometimes referred to as a "V Grind", made with strength in mind and found on tactical and military knives. A Sabre grind without a secondary bevel is called a "Scandinavian Grind," which is easier to sharpen due to the large surface. The Finnish puukko is an example of a Scandinavian ground knife.

- Chisel grind — As on a chisel, only one side is ground (often at an edge angle of about 20 – 30°); the other remains flat. As many Japanese culinary knives tend to be chisel ground they are often sharper than a typical double bevelled Western culinary knife; a chisel grind has only a single edge angle; if a sabre ground blade has the same edge angle as a chisel grind, it still has angles on both sides of the blade centerline, and so has twice the included angle. Knives that are chisel ground come in left and right-handed varieties, depending upon which side is ground. Japanese knives feature subtle variations on the chisel grind: firstly, the back side of the blade is often concave, to reduce drag and adhesion so the food separates more cleanly; this feature is known as urasuki.[2] Secondly, the kanisaki deba, used for cutting crab and other shellfish, has the grind on the opposite side (left side angled for right-handed use), so that the meat is not cut when chopping the shell.[3]

- Double bevel or compound bevel — A back bevel, similar to a sabre or flat grind, is put on the blade behind the edge bevel (the bevel which is the foremost cutting surface). This back bevel keeps the section of blade behind the edge thinner which improves cutting ability. Being less acute at the edge than a single bevel, sharpness is sacrificed for resilience: such a grind is much less prone to chipping or rolling than a single bevel blade. This profile is commonly found in Japanese swords, such as the familiar katana. The shape of the bevel is much more efficient in reducing drag than the sabre grind typically found on Western sword blades. In practice, double bevels are common in a variety of edge angles and back bevel angles, and Western kitchen knives generally have a double bevel, with an edge angle of 14-16° (included angle of 28-32°) and a maximum of 40° as specified by International standard ISO 8442.1 (knives for the preparation of food).

- Convex grind — Rather than tapering with straight lines to the edge, the taper is curved, though in the opposite manner to a hollow grind. Such a shape keeps a lot of metal behind the edge making for a stronger edge while still allowing a good degree of sharpness. This grind can be used on axes and is sometimes called an axe grind. As the angle of the taper is constantly changing this type of grind requires some degree of skill to reproduce on a flat stone. Convex blades usually need to be made from thicker stock than other blades.[1] This is also known as hamaguriba in Japanese kitchen knives, both single and double beveled. Hamaguriba means "clam-shaped edge".

It is possible to combine grinds or produce other variations. For example, some blades may be flat ground for much of the blade but be convex ground towards the edge.