Great Boston fire of 1872

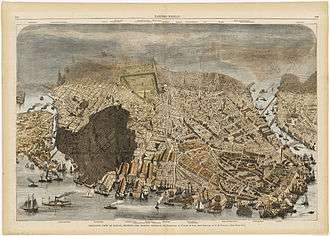

The Great Boston fire of 1872 was Boston's largest fire, and still ranks as one of the most costly fire-related property losses in American history. The conflagration began at 7:20 p.m. on November 9, 1872, in the basement of a commercial warehouse at 83-87 Summer Street. The fire was finally contained 12 hours later, after it had consumed about 65 acres (26 ha) of Boston's downtown, 776 buildings and much of the financial district, and caused $73.5 million in damage.[1] Despite these devastations, only thirteen people died in the inferno.[2]

Underlying causes

Many factors contributed to Boston's Great Fire:

- Boston's building regulations were not enforced. There was no authority to stop faulty construction practices.

- Buildings were often insured at full value or above value. Over-insurance meant owners had no incentive to build fire-safe buildings. Insurance-related arson was common.

- Flammable wooden French Mansard roofs were common on most buildings. The fire was able to spread quickly from roof to roof, and flames even leapt across the narrow streets onto other buildings. Flying embers and cinders started fires on even more roofs.

- Fire alarm boxes in Boston were locked to prevent false alarms, therefore delaying the Boston Fire Department by twenty minutes.

- Merchants were not taxed for inventory in their attics, therefore offering incentive to stuff their wood attics with flammable goods such as wool, textiles, and paper stocks.

- Most of the downtown area had old water pipes with low water pressure.

- Fire hydrant couplings were not standardized.

- The number of fire hydrants and cisterns was insufficient for a commercial district.

- A horse flu epizootic had immobilized Boston's fire department horses. As a result, all of the fire equipment had to be pulled to the fire by teams of volunteers on foot. This is often cited as the leading cause of this fire growing out of control, but the city commission investigating the fire found that fire crews' response times were delayed by only a matter of minutes.

- Looters and bystanders interfered with fire fighting efforts.

- Steam engine pumpers were not able to draw enough water to reach the wooden roofs of tall downtown buildings.

- Gas supply lines connected to street lamps and used for lighting in buildings could not be shut off promptly. Gas lines exploded and fed the flames.

Events

Notable events of the fire:

- Author Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. watched the fire from his home on Beacon Hill. He wrote a poem about the event called "After the Fire".

- Alexander Graham Bell wrote his own eyewitness account of the fire in a letter to the newspaper The Boston Globe. Unimpressed by Bell's prose, the paper did not publish his letter.

- The Great Chicago Fire had occurred just one year earlier, in October 1871.

- A committee of concerned citizens and property owners were deputized to demolish buildings in the path of the fire with gunpowder kegs. The explosions did more harm than good by most accounts.

- The glow in the sky over the fire was noted in ship's logs off the coast of Maine.

- Fire departments from every state in New England, except Vermont, arrived on trains carrying pumpers, fire fighters, and more spectators.

- Of these were two Amoskeag Steamers from Manchester, New Hampshire. One was the first Amoskeag ever constructed (serial number 1), owned by the Manchester Fire Department; the other was the first self-propelled Amoskeag that the manufacturer sent down. Boston purchased the self-propelled steamer after the fire, impressed with its performance. The self-propelled steamer was the first one in use in the country.[3]

- Looters had to be chased out of burning buildings.

- Old South Meeting House on Washington Street, the church in which the Boston Tea Revolt was organized, was saved from the fire. The Kearsarge Steam Fire Engine from Portsmouth, New Hampshire may have aided in the effort to save the historic building.

- The buildings of businesses well known in Boston today that burned in the fire include:

- The Boston Globe newspaper

- The Boston Herald newspaper

- Shreve, Crump & Low jewelry store

- Carter's Ink Company

- Harvey W. Wiley took part in fighting the fire while he was a student at Harvard University. He later wrote about it in his autobiography.

Aftermath

A 2017 study in the American Economic Review found that the Fire through the replacement of outdated buildings with upgraded buildings initiated "a virtuous circle in which building upgrades encouraged further upgrades of nearby buildings. Land values increased substantially among burned plots and nearby unburned plots, capitalizing economic gains comparable to the prior value of burned buildings. Boston had grown rapidly prior to the Fire, but negative spillovers from outdated durable buildings had substantially constrained its growth by dampening reconstruction incentives."[4]

The fire rendered thousands of Bostonians jobless and homeless. Hundreds of businesses were destroyed, and dozens of insurance companies went bankrupt. However, the burnt district was quickly rebuilt in just under two years, mostly from the private capital of Boston's commercial property owners.

City planning during the post-fire reconstruction caused several streets in downtown Boston to be widened, particularly Congress Street, Federal Street, Purchase Street, and Hawley Street, and reserved the space for Post Office Square. Most of the rubble and ruins of the buildings destroyed by the fire was dumped in the harbor to fill in Atlantic Avenue.

Boston issued bonds for use by 16 private property owners in the downtown area to rebuild. A citizen who lived outside the area sued successfully, arguing that the bonds were a transfer of wealth from one set of citizens to another.

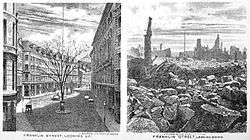

Image gallery

References

- ↑ "The Rebuilding of Boston. One Year After the Great Fire. November 10, 1872" (Archived at Damrell’s Fire). Boston Morning Journal. XL (13): 509. 1873-11-10. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ↑ Robert J. Allison, A Short History of Boston, page 74.

- ↑ Steve Pearson. "Interesting facts about the department". Manchesterfirehistory.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2011.

- ↑ Richard, Hornbeck,; Daniel, Keniston, (June 2017). "Creative Destruction: Barriers to Urban Growth and the Great Boston Fire of 1872". American Economic Review. 107 (6): 1365. doi:10.1257/aer.20141707&etoc=1. ISSN 0002-8282.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Boston fire of 1872. |

- Boston Public Library on Flickr. Collection of images related to the fire.

- Flash Map of Fire from MapJunction

- Boston Fire Department History

- Boston, MA The Great Fire, Nov 1872, GenDisasters.com

Coordinates: 42°21′13.75″N 71°3′30.80″W / 42.3538194°N 71.0585556°W

.jpg)

.jpg)