Gobiesocidae

| Clingfishes | |

|---|---|

| |

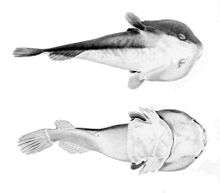

| Aspasmogaster tasmaniensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Superorder: | Acanthopterygii |

| Order: | Gobiesociformes |

| Family: | Gobiesocidae Bleeker, 1860 |

Clingfishes are fishes of the family Gobiesocidae, belonging to the order Gobiesociformes. These fairly small to very small fishes are widespread in tropical and temperate regions, mostly near the coast, but a few species in deeper seas or fresh water. Most species shelter in shallow reefs or seagrass beds, clinging to rocks, algae and seagrass leaves with their sucking disc, a structure on their chest.[1][2]

They are generally too small to be of interest to fisheries, although the relatively large Sicyases sanguineus regularly is caught as a food fish,[3] and some of the other species occasionally appear in the marine aquarium trade.[1]

Distribution and habitat

Clingfishes are primarily found near the shore in tropical and temperate parts of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans, including marginal seas such as the Mediterranean, Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean and Gulf of California. Here they mainly inhabit shallow rocky reefs and shores, coral reefs, seagrass meadows and algae beds. They often live in places exposed to strong currents and wave action, and some are amphibious. As long as the strongly amphibious, intertidal-living species are kept moist by splashing waves, they can survive for up to three–four days on land, gaining oxygen from the air by the branchial surfaces (gills), skin and perhaps the mouth.[4][5][6] At least a few species even tolerate a relatively high degree of water loss when on land.[5]

Some species shelter in sea urchins or crinoids, or cling onto the bodies of larger fish where they act as cleaners.[1] Although several species can occur in brackish water, only seven (Gobiesox cephalus, G. fluviatilis, G. fulvus, G. juniperoserrai, G. juradoensis, G. mexicanus and G. potamius) from warmer parts of the Americas are freshwater fish that live in fast-flowing rivers and streams.[7][8]

Most known clingfish species are from relatively shallow coastal waters, but several inhabit the mesophotic zone and a few even deeper, with Alabes bathys, Gobiesox lanceolatus, Gymnoscyphus ascitus, Kopua kuiteri, K. nuimata and Protogobiesox asymmetricus reported from depths of 300–560 m (980–1,840 ft).[9][10] Because of their small size and typical habitat, it is however suspected than still-undiscovered deep-water species remain.[9] Even in shallow coastal waters many clingfish are highly cryptic and easily overlooked, mostly staying under cover, although there are species that are active and will swim in the open.[11] As a consequence their abundance is often not well known. Several species are only known from a single or a few specimens.[9][10][12] Species that appear uncommon or rare based on standard methods can actually be common if using methods that are more suitable for detecting them.[13] Studies of better-known species have shown that they can be locally abundant. As many as 23 individuals of Lepadogaster lepadogaster have been documented from a single square metre (more than two individuals per square foot).[14] As of 2018, the IUCN has evaluated the conservation status of 84 clingfish species (roughly half the species in the family). The majority of these are considered least concern (not threatened), 17 are considered data deficient (available data prevents an evaluation), 8 considered vulnerable and a single endangered. The vulnerable and endangered species all have small distributions, restricted to islands or a single bay.[15] Three Gobiesox species that are restricted to fresh water in Mexico have not been rated by the IUCN, but are considered threatened by Mexican authorities.[16]

Description

Clingfishes are typically small fish, with most species less than 7 cm (2.8 in) in length,[17] and the smallest no more than 1.5 cm (0.6 in).[1] Only a few species can surpass 12 cm (4.7 in) in length and the largest, Chorisochismus dentex and Sicyases sanguineus, both reach up to 30 cm (12 in).[5][18] Males typically grow larger than females.[2]

Most clingfish species have tapering bodies and flattened heads, appearing somewhat tadpole-like in their overall shape. The lateral line of clingfish is well developed, but may not extend to the posterior parts of the body. The skin of clingfishes is smooth and scaleless, with a thick layer of protective mucus.[2] In at least Diademichthys lineatus and Lepadichthys frenatus the mucus production increases if the fish is disturbed and it has a highly bitter taste. This is possibly related to their skin containing a grammistin-like toxin (the toxin in soapfish, such as Grammistes). Whether any other clingfish has toxins in its skin or mucus is currently unknown.[19] Another defense appears to be present in a couple of Acyrtus and Arcos species. They have a spine at their gill cover and it appears to be connected to a venom gland. Although the evidence presently is circumstantial, this strongly suggests that the world's smallest venomous fish is Acyrtus artius, which is less than 3 cm (1.2 in) long.[20][21]

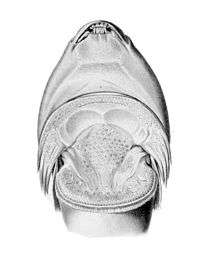

Sucking disc

Clingfish are named for their ability to firmly attach themselves to various surfaces, even in strong water currents or when battered by waves. This ability is aided by their sucking disc, which is located on the underside at the chest and is formed primarily by modified pelvic fins and adjacent tissue.[2][5][6][17] In some species it is divided in two, resulting in a larger front and a smaller rear sucking disc.[2] The sucking disc is covered in tiny hexagons and each of these consists of many microscopic hair-like structures. This is similar to the structures that allow geckos to cling to walls. The sucking disc can be remarkably strong, in some species able to lift as much as 300 times the weight of the clingfish.[6] Gobies (family Gobiidae) can have a similar sucking disc, but unlike that family the single dorsal fin in clingfish is not spiny.[2] In a few clingfish species the disc is reduced or even absent, notably Alabes, which are quite eel-like in their shape and aptly named shore-eels.[1][22] The sucking disc is also reduced in some deep-water clingfish species.[6]

Colours

Most clingfish species have a cryptic colouration, often brown, grey, black, reddish or green shades, and in some cases they can rapidly change colour to match their background.[2][23] Species of deep water are often orange-red (these long wave-length colours are the first that disappear with depth, making them suitable for camouflage),[10] and Diademichthys lineatus, Discotrema and Lepadichthys lineatus have a strongly banded pattern (a suitable camouflage for species living among sea urchin spines or crinoid arms).[19][24] There are species with colours less suitable for camouflage. Although Lepadogaster purpurea overall is cryptic, it has a pair of distinct large eyespots on the top of its head.[25] The Australian Cochleoceps bicolor and C. orientalis, and warm East Atlantic Diplecogaster tonstricula are yellow to red with fine bluish lines. These three are cleaner fish.[22][26]

Classification and taxonomy

The classification of the clingfishes varies. FishBase places Gobiesocidae as the only family in the order Gobiesociformes, under the superorder Paracanthopterygii;[27] whereas ITIS place them in the suborder Gobiesocoidei of the order Perciformes, under superorder Acanthopterygii. ITIS lists Gobiesociformes as invalid.[28]

Mostly being very small and often cryptic, new species are regularly discovered and described. A major authoritative work on the family is a monograph that was published in 1955 by J.C. Briggs,[29] but in the half century after its publication, up until 2006, fifty-six new clingfish species were described, or on average more than one per year.[19] This pattern with regular descriptions of new species—and even new genera—has continued since then.[9][10][12][19][30][31]

Subfamilies and genera

Subfamily Cheilobranchinae

Subfamily Gobiesocinae

- Acyrtops

- Acyrtus

- Apletodon

- Arcos

- Aspasma

- Aspasmichthys

- Aspasmodes

- Aspasmogaster

- Briggsia

- Chorisochismus

- Cochleoceps

- Conidens

- Creocele

- Dellichthys

- Derilissus

- Diademichthys

- Diplecogaster

- Diplocrepis

- Discotrema

- Eckloniaichthys

- Gastrocyathus

- Gastrocymba

- Gastroscyphus

- Gobiesox

- Gouania

- Gymnoscyphus

- Haplocylix

- Kopua

- Lecanogaster

- Lepadichthys

- Lepadogaster

- Liobranchia

- Lissonanchus

- Modicus

- Opeatogenys

- Parvicrepis

- Pherallodichthys

- Pherallodiscus

- Pherallodus

- Posidonichthys

- Propherallodus

- Rimicola

- Sicyases

- Tomicodon

- Trachelochismus

- Unguitrema[30]

Subfamily Protogobiesocinae

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bray, Dianne. "Family GOBIESOCIDAE". Fishes of Australia. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Donaldson, T.J. (2004). "Gobiesocoidei (Clingfishes And Singleslits)". encyclopedia.com. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ Paine, R.T.; A.R. Palmer (1978). "Sicyases sanguineus: a Unique Trophic Generalist from the Chilean Intertidal Zone". Copeia. 1978 (1): 75–81.

- ↑ Ebeling, A.W.; P. Bernal; A. Zuleta (1970). "Emersion of the amphibious Chiliean clingfish, Sicyastes sanguineus". Biol Bull. 139 (1): 115–137. doi:10.2307/1540131.

- 1 2 3 4 Graham, J.B., ed. (1997). Air-Breathing Fishes: Evolution, Diversity, and Adaptation. Academic Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-12-294860-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Simon, M. (6 June 2014). "Absurd Creature of the Week: This Fish Can Support 300 Times Its Weight With a Super Suction Cup". wired.com. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ Conway, K.W.; D. Kim; L. Rüber; H.S. Espinosa Pérez; P.A. Hastings (2017). "Molecular systematics of the New World clingfish genus Gobiesox (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae) and the origin of a freshwater clade". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 112: 138–147. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2017.04.024.

- ↑ Mercado-Silva, N.; J.J. Schmitter-Soto; H. Espinosa-Pérez (2016). "Overlap of mountain clingfish (Gobiesox fluviatilis) and Mexican clingfish (Gobiesox mexicanus) in the Cuitzmala River, Jalisco, Mexico". The Southwestern Naturalist. 61 (1): 83–87.

- 1 2 3 4 Hastings, P.A.; K.W. Conway (2017). "Gobiesox lanceolatus, a new species of clingfish (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae) from Los Frailes submarine canyon, Gulf of California, Mexico". Zootaxa. 4221 (3): 393–400. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4221.3.8.

- 1 2 3 4 Moore, G.I.; J.B. Hutchins; M. Okamoto (2012). "A new species of the deepwater clingfish genus Kopua (Gobiesociformes: Gobiesocidae) from the East China Sea—an example of antitropicality?". Zootaxa. 3380: 34–38.

- ↑ Almada, F.; M. Henriques; A. Levy; A. Pereira; J. Robalo; V.C. Almada (2008). "Reclassification of Lepadogaster candollei based on molecular and meristic evidence with a redefinition of the genus Lepadogaster". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 46 (3): 1151–1156. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.05.021.

- 1 2 Ma, M. (17 April 2017). "New many-toothed clingfish discovered with help of digital scans". University of Washington. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Craig, M.T.; Williams, J.T. (2015). "Arcos nudus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T185939A1792278. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T185939A1792278.en. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Wagner, M.; S. Bračun; M. Kovačić; S.P. Iglésias; D.Y. Sellos; S. Zogaris; S. Koblmüller (2017). "Lepadogaster purpurea (Actinopterygii: Gobiesociformes: Gobiesocidae) from the eastern Mediterranean Sea: Significantly extended distribution range". Acta Ichthyologica Et Piscatoria. 47 (4): 417–421. doi:10.3750/AIEP/02244.

- ↑ The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (12 October 2018). "Gobiesocidae". Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ↑ Ceballos, G.; E.D. Pardo; L.M Estévez; H.E. Pérez, eds. (2016). Los peces dulceacuícolas de México en peligro de extinción. pp. 420–426. ISBN 978-607-16-4087-1.

- 1 2 Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Gobiesocidae" in FishBase. October 2012 version.

- ↑ Lubke, R., & I. De Mour (1998). Field Guide to the Eastern and Southern Cape Coasts. ISBN 978-1919713038

- 1 2 3 4 Craig, M.T.; J.E. Randall (2008). "Two New Species of the Indo-Pacific Clingfish Genus Discotrema (Gobiesocidae)". Copeia. 2008 (1): 68–74.

- ↑ Conway, K.W.; C. Baldwin; M.D. White (2014). "Cryptic Diversity and Venom Glands in Western Atlantic Clingfishes of the Genus Acyrtus (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae)". PLOS One. 9 (5): e97664. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097664.

- ↑ Keartes, S. (22 May 2014). "Could This be the World's Smallest Venomous Fish?". Earth Touch News. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- 1 2 Hutchins, B.; R. Swainston (1986). Sea Fishes of Southern Australia. Swainston Publishing, Perth. pp. 32–33. ISBN 1-86252--661-3.

- ↑ Briggs, J.C.; Hutchins, J.B. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N., eds. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-12-547665-2.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2018). "Diademichthys lineatus" in FishBase. October 2018 version.

- ↑ Henriques, M.; R. Lourenco; F. Almada; G. Calado; D. Gonçalves; T. Guillemaud; M.L. Cancela; V.C. Almada (2002). "A revision of the status of Lepadogaster lepadogaster (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae): sympatric subspecies or a long misunderstood blend of species?". Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 76 (1): 327–338. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2002.00067.x.

- ↑ Fricke, R.; P. Wirtz; A. Brito (2015). "Diplecogaster tonstricula, a new species of cleaning clingfish (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae) from the Canary Islands and Senegal, eastern Atlantic Ocean, with a review of the Diplecogaster-ctenocrypta species-group". Journal of Natural History. 50 (11–12): 731–748. doi:10.1080/00222933.2015.1079659.

- ↑ Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2012). "Gobiesociformes" in FishBase. october 2012 version.

- ↑ "Gobiesociformes". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- ↑ Briggs, J.C. (1955). "A monograph of the clingfishes (Order Xenopterygii)". Stanford Ichthyological Bulletin. 6: 1–224.

- 1 2 Fricke, R. (2014). "Unguitrema nigrum, a new genus and species of clingfish (Teleostei: Gobiesocidae) from Madang, Papua New Guinea" (PDF). Journal of the Ocean Science Foundation. 13: 35–42.

- 1 2 Fricke, R., Chen, J.-N. & Chen, W.-J. (2016): New case of lateral asymmetry in fishes: A new subfamily, genus and species of deep water clingfishes from Papua New Guinea, western Pacific Ocean. Comptes Rendus Biologies, 340 (1): 47–62.

External links

- Smith, J.L.B. 1964. The clingfishes of the Western Indian Ocean and the Red Sea. Ichthyological Bulletin; No. 30. Department of Ichthyology, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gobiesocidae. |