Global illumination

Global illumination[1] (shortened as GI), or indirect illumination, is a general name for a group of algorithms used in 3D computer graphics that are meant to add more realistic lighting to 3D scenes. Such algorithms take into account not only the light that comes directly from a light source (direct illumination), but also subsequent cases in which light rays from the same source are reflected by other surfaces in the scene, whether reflective or not (indirect illumination).

Theoretically, reflections, refractions, and shadows are all examples of global illumination, because when simulating them, one object affects the rendering of another (as opposed to an object being affected only by a direct light). In practice, however, only the simulation of diffuse inter-reflection or caustics is called global illumination.

Algorithms

Images rendered using global illumination algorithms often appear more photorealistic than those using only direct illumination algorithms. However, such images are computationally more expensive and consequently much slower to generate. One common approach is to compute the global illumination of a scene and store that information with the geometry (e.g., radiosity). The stored data can then be used to generate images from different viewpoints for generating walkthroughs of a scene without having to go through expensive lighting calculations repeatedly.

Radiosity, ray tracing, beam tracing, cone tracing, path tracing, Metropolis light transport, ambient occlusion, photon mapping, and image based lighting are all examples of algorithms used in global illumination, some of which may be used together to yield results that are not fast, but accurate.

These algorithms model diffuse inter-reflection which is a very important part of global illumination; however most of these (excluding radiosity) also model specular reflection, which makes them more accurate algorithms to solve the lighting equation and provide a more realistically illuminated scene. The algorithms used to calculate the distribution of light energy between surfaces of a scene are closely related to heat transfer simulations performed using finite-element methods in engineering design.

Photorealism

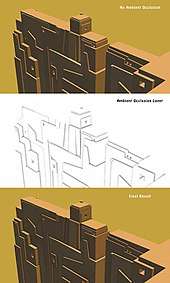

Achieving accurate computation of global illumination in real-time remains difficult.[2] In real-time 3D graphics, the diffuse inter-reflection component of global illumination is sometimes approximated by an "ambient" term in the lighting equation, which is also called "ambient lighting" or "ambient color" in 3D software packages. Though this method of approximation (also known as a "cheat" because it's not really a global illumination method) is easy to perform computationally, when used alone it does not provide an adequately realistic effect. Ambient lighting is known to "flatten" shadows in 3D scenes, making the overall visual effect more bland. However, used properly, ambient lighting can be an efficient way to make up for a lack of processing power.

Procedure

More and more specialized algorithms are used in 3D programs that can effectively simulate the global illumination. These algorithms are numerical approximations to the rendering equation. Well known algorithms for computing global illumination include path tracing, photon mapping and radiosity. The following approaches can be distinguished here:

- Inversion:

- is not applied in practice

- Expansion:

- bi-directional approach: Photon mapping + Distributed ray tracing, Bi-directional path tracing, Metropolis light transport

- Iteration:

In Light path notation global lighting the paths of the type L (D | S) corresponds * E.

A full treatment can be found in [3]

Image-based lighting

Another way to simulate real global illumination is the use of High dynamic range images (HDRIs), also known as environment maps, which encircle and illuminate the scene. This process is known as image-based lighting.

List of methods

| Method | Description/Notes |

|---|---|

| Ray tracing | Several enhanced variants exist for solving problems related to sampling, aliasing, soft shadows: Distributed ray tracing, Cone tracing, Beam tracing. |

| Path tracing | Unbiased, Variant: Bi-directional Path Tracing, Energy Redistribution Path Tracing[4] |

| Photon mapping | Consistent, biased; enhanced variants: Progressive Photon Mapping, Stochastic Progressive Photon Mapping ([5]) |

| Lightcuts | enhanced variants: Multidimensional Lightcuts, Bidirectional Lightcuts |

| Point Based Global Illumination | Extensively used in movie animations[6][7] |

| Radiosity | Finite element method, very good for precomputations. Improved versions Instant Radiosity[8] and Bidirectional Instant Radiosity[9] |

| Metropolis light transport | Builds upon bi-directional path tracing, unbiased, Multiplexed[10] |

| Spherical harmonic lighting | Encodes global illumination results for real-time rendering of static scenes |

| Ambient occlusion | Not a physically correct method, but gives good results in general. Good for precomputation. |

| Voxel-based Global Illumination | Several variants exist including Voxel Cone Tracing Global Illumination,[11] Sparse Voxel Octree Global Illumination and Voxel Global Illumination (VXGI)[12] |

| Light Propagation Volumes Global Illumination[13] | Light propagation volumes is a technique to approximately achieve global illumination (GI) in Real-time.

It uses lattices and spherical harmonics (SH) to represent the spatial and angular distribution of light in the scene. Variant Cascaded Light Propagation Volumes.[14] |

| Deferred Radiance Transfer Global Illumination[15] | |

| Deep G-Buffer based Global Illumination[16] |

See also

- Category:Global illumination software

- Bias of an estimator

- Bidirectional scattering distribution function

- Consistent estimator

- Unbiased rendering

References

- ↑ "Realtime Global Illumination techniques collection | extremeistan". extremeistan.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ↑ Kurachi, Noriko (2011). The Magic of Computer Graphics. CRC Press. p. 339. ISBN 9781439873571. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ↑ Philip Dutre; Philippe Bekaert; Kavita Bala (August 30, 2006). Advanced Global Illumination, Second Edition. ISBN 978-1568813073.

- ↑ "CiteSeerX — Abstract". citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ↑ "Toshiya Hachisuka at UTokyo". ci.i.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ↑ "coursenote.dvi" (PDF). Graphics.pixar.com. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-22. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- ↑ "Instant Radiosity : Keller (SIGGRAPH 1997)" (PDF). Cs.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ "Bidirectional Instant Radiosity" (PDF). Artis.imag.fr. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ "Multiplexed Metropolis Light Transport" (PDF). Ci.i.u-tokyo.ac.jp. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ Cyril Crassin. "Voxel Cone Tracing and Sparse Voxel Octree for Real-time Global Illumination" (PDF). On-demand.gputechconf.com. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ "VXGI | GeForce". geforce.com. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ↑ "Light Propagation Volumes GI - Epic Wiki". wiki.unrealengine.com. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-01-18. Retrieved 2016-01-23.

- ↑ "Deferred Radiance Transfer Volumes : Global Illumination in Far Cry 3" (PDF). Twvideo01.ubm-us.net. Retrieved 2016-12-02.

- ↑ "Fast Global Illumination Approximations on Deep G-Buffers". graphics.cs.williams.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-14.

External links

- Video demonstrating global illumination and the ambient color effect

- Real-time GI demos – survey of practical real-time GI techniques as a list of executable demos

- kuleuven - This page contains the Global Illumination Compendium, an effort to bring together most of the useful formulas and equations for global illumination algorithms in computer graphics.

- Theory and practical implementation of Global Illumination using Monte Carlo Path Tracing.