Gioachino Greco

Gioacchino Greco (c. 1600 – c. 1634) was an Italian chess player and writer. He recorded some of the earliest chess games known in their entirety. His games, all given with anonymous opponents ("NN", for the Latin nomen nescio), were quite possibly constructs (Hooper & Whyld 1992), but served as highly useful tools for spotting opening traps.

Mikhail Botvinnik considered Greco to be the first professional chess player (Gufeld & Stetsko 1996:5).

Greco was also known in Italy as il Calabrese ("the Calabrian"). Some sources quote that his parents were Greeks and that he had been born at Celico, a village near Cosenza (Murray 2012:828).

Life

Little is known about the life of Greco. He was born around 1600 in Calabria- from which he took his sobriquet- and apparently showed an early aptitude for chess. Mariano Marano, an eminent Italian player of the day, took him as a student. By 1620 Greco had become skilled enough to write his first manuscript, copies of which were given to his patrons in Rome (Leon 1900:xv).

Greco soon traveled to Paris, where he continued to find great success over the board. His victories over the strongest French players- among them the Duc de Nemours, M. Arnault le Carabin, and M. Chaumont de la Salle- granted him both fame and riches; by 1622 Greco was travelling to England with an extra 5,000 crowns. (Leon 1900: xvi)

Greco is said to have been waylaid during this journey, however, resulting in the loss of his newfound wealth. Undeterred, he continued to London and defeated the English chess elite. During his stay in London Greco began recording entire chess games rather than single instructive positions, as had been the usual manner. (Leon 1900:xvi)

Greco returned to Paris in 1624 and began rewriting his collection of manuscripts to describe entire games (Leon 1900:xvi). It is unclear whether he actually played these games- to modern eyes, his opponents' play seems dubious at best. The games' provenance is perhaps inessential; having composed them, Greco was certainly capable of playing them on a board.

Not one to remain in one place for long, Greco left Paris for the court of Philip IV in Spain. Aside from the eminent Spanish players, Greco also happened to encounter and defeat his old mentor Mariano Morano. By this point Greco had shown himself to be the greatest player in Europe with victories over the champions of Rome, Paris, London, and Madrid. (Leon 1900:xvi)

Having conquered the Old World, Greco traveled to the New. Although no man could defeat him in chess, Greco succumbed to disease in the East Indies soon after arriving. The exact date of Greco's death is unknown, but he was certainly dead by 1634 (Leon 1900:xvi).

Legacy

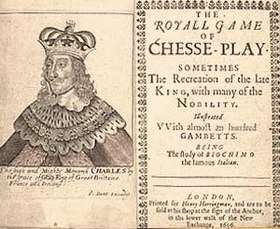

Greco was a remarkable chess player who inhabited the era between Ruy López de Segura and François-André Danican Philidor. At that early date, no great corpus of chess knowledge had yet been amassed. It is for this reason that Greco's games should be understood as those of a brilliant inventor and pioneer rather than as guides to sound play. They are also valuable examples of the Italian Romantic school of chess, in which development and material are eschewed in favor of aggressive attacks on the opponent's king. Greco paved the way for many of the attacking legends of the Romantic era, such as Adolf Anderssen, Paul Morphy, and François Philidor, Greco's innovation to record entire games is perhaps his greatest legacy. In 1656, years after his death, Greco's manuscripts were collected and published as The Royall Game of Chesse-Play by Francis Beale in London (Leon 1900). These games were not described in the now-familiar algebraic notation; rather, the movement of each piece was given in order like so:

The Fooles Mate.

Black Kings Bishops pawne one house.

White Kings pawne one house.

Black kings knights pawne two houses

White Queen gives Mate at the contrary kings Rookes fourth house

in which "house" refers to a square on the chessboard. (Herringman 1656:18)

In addition to the games ("Gambetts") listed in his manuals, Greco gave an overview of the rules of chess ("The Lawes of Chesse") and general advice to his readers. These range from the familiar ("If you touch your man you must play it, and if you set it downe any where you must let it stand") to the bizarre ("If at first you misplace your men, and play two or three draughts, it lieth in your adversaries choice whether you shall play out the game or begin it again.") (Herringman 1656:15). Greco also describes the premodern necessity of announcing check to ones opponent and the disgrace of what he calls a "blind Mate"- a checkmate given but not noticed (Herringman 1656:13).

The "Lawes of Chesse" were also not entirely standardized in Greco's time, and he specifies that when castling in France, "the Rook... goeth into the Kings house." Standard castling, which Greco also describes, is sometimes called "alla Calabrese" in Greco's honor. (Walker, 1831:6)

Example games

As one of the players during the age of the Italian Romantic style, Greco studied the Giuoco Piano (1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5), among other openings. These games are regarded as classics of early chess literature and are sometimes still taught to beginners.

Among his games/constructions were the first smothered mate:

- NN vs. Greco, 1620

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.0-0 Nf6 5.Re1 0-0 6.c3 Qe7 7.d4 exd4 8.e5 Ng4 9.cxd4 Nxd4 10.Nxd4 Qh4 11.Nf3 Qxf2+ 12.Kh1 Qg1+ 13.Nxg1 Nf2# 0–1

and this impressive queen sacrifice:

- Greco vs. NN, 1619

1.e4 b6 2.d4 Bb7 3.Bd3 f5 4.exf5 Bxg2 5.Qh5+ g6 6.fxg6 Nf6 7.gxh7+ Nxh5 8.Bg6# 1–0

Composition

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

| 8 |  | 8 | |||||||

| 7 | 7 | ||||||||

| 6 | 6 | ||||||||

| 5 | 5 | ||||||||

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||

| 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | ||

This composition by Greco uses the theme of the wrong rook pawn:

Quotes About Gioachino Greco

- "Greco was the Morphy of the seventeenth century, and it may safely be said that in brilliancy and fertility of invention he has never been surpassed." (Leon 1900:xiii)

- "The games of Calabrisian Greco can be considered as a great education for beginners and intermediate players; even the most dedicated connoisseur of the board wants to find in its many unknown twists and elegant ways of playing, which enrich or round off his experiences." (translated from German, Max Lange) (Leon 1900:xx)

- "[B]y your proud march all my projects are down: see, as you go, all my defenses give way, fall all my champions in vain resistance, King; Knight, Rook and Bishop are less than your pawns." (translated from French, unknown) (Leon 1900:xvi)

See also

References

- Averbakh, Yuri (1996), Chess Middlegames: Essential Knowledge, Cadogan, ISBN 1-85744-125-7

- Gufeld, Eduard; Stetsko, Oleg (1996), The Giuoco Piano, Batsford, ISBN 0-7134-7802-0

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1992), The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280049-3

- Murray, H. J. R. (2012) [1913], A History of Chess, Skyhorse, ISBN 978-1-62087-062-4

- Leon, J.A. and Hoffman (1900), The Games of Greco, G. Routledge.

- Walker, George (1831), A New Treatise on Chess. Sherwood, Gilbett and Piper.

- Herringman, H. (1656)The Royall Game of Chesse-Play, Sometimes the Recreation of the Late King, with Many of the Nobility. London.

External links

- Gioachino Greco player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- Works by or about Gioachino Greco in libraries (WorldCat catalog)