Gender inequality in Japan

Japan is a high income society that has high levels of gender inequality. In 2015 Japan had per capita income of 38,883 dollars [1], which ranked it #22 among 188 countries and it ranked 17 in HNDP's HDI [2], yet its GII rank was # 21.[3] This disparity between welfare achieved and gender inequality owes to persistence of gender norms. Gender inequality manifests in various aspects of social life from the family to political representation.

Family Values

Japan's family values have historically been shaped by the typical female housewife/caregiver and the male earner gender division of labor. After the U.S forced Japan's surrender, the new Japanese Constitution included article 24 "The Gender Equality Cause" was formed to veer Japan into a more equal environment for both sexes. Resistance to change as a result of the familial culture led to a continued gender inequality in Japan.[4]

It was not until the mid 1970's that Japanese women began stepping down from family duties and finally playing a larger role in "visible" paid economy. While Japanese men did not step into play a larger role in the house. Studies have shown that there is a negative correlation between the number of hours and the amount of housework (including childcare) that the father provides.[5] After work the father will come home, spend most of his time eating or conducting in non-social interactions such as quietly eating dinner in front of the T.V with his children or family and then sleep to repeat the cycle.[5] This posed the term "Japan INC" which was synonymous with males committing their life with their work in a long term relationship. [6]

Another term that struck popularity within Japan was "relationless society" as the constant time at work for males left little to no time at home for them to connect with their families. Society in Japan slowly came to be one of isolation within the household, you would need to take care of yourself as there was no time to take care of each other.[6] This holds especially true for families who wish to have a second child. Due to corporation and work regulation laws, men in large firms are subject to having a work life balance that solely favors their work.[7] This type of behavior is continued through recent graduates who begin working at large firms and have little to no time to help around the house. The limited amount of time forces the women of the house to take up household chores and activities.[7]

Social Stratification Mobility Survey

The SSM (Social Stratification and Mobility) survey was first conducted post WWII and was a continuous effort every decade thereafter.[8] The first SSM survey took place in 1955 and the goal of the survey was to study the economic and equality foundation of Japan after the events of the second world war. A large scale survey like the SSM has its problems. At a national level, many local issues go unnoticed and inequality stays hidden behind the curtains of households until a more focused survey can unveil more.[8]

In Japan, even a focus on a large scale survey was progress and it was not until the fourth survey in 1985 that there was a remarkable change in a move towards equality.[8] Up until the fourth survey, women were only counted as housewives and family business labor (help with family owned businesses like farm work or light labor) was not considered towards economic mobility.[8] It is here that we finally start to see a shift to a more equal country.

The Equal Employment Opportunity Law (EEOL)

With national surveys finally including women, the government began to step in by introducing the Equal Employment Opportunity Law. Before the enactment of the EEOL, women were subjected to intensive labor jobs such as farm labor and blue collared jobs working in the factories with poor health conditions. Women who were lucky enough to stay away from the labor were instead places as secretaries or assistants to high ranking males in office work [8]. Post EEOL Japan began to see blue collar jobs fill up with machines leaving the women to have better opportunities elsewhere in society [8].

This law was supposed to create a field of equality within the workforce for males and females. Like any societal changing law, despite the definition of the law, women were still being discriminated against in all areas of the workforce.. [9] Despite prevalent discrimination, modern Japan continues to push forward with the EEOL and other such equality laws like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) with new initiatives and positions of power for women. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe placed 5 women into political roles within his cabinet in 2014. Of these 5 women, only 3 kept their positions due to scandals inferring to the discrimination that women still face within Japanese society [10]

Gender Inequality Index

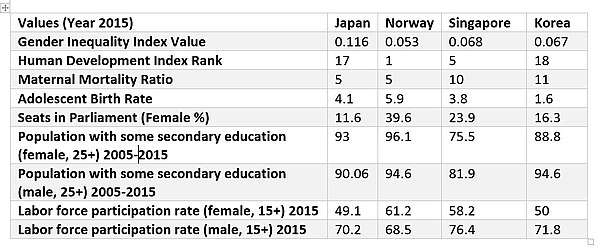

The Gender Inequality Index for Japan, as of 2016 is currently listed at rank 21 out of 188 countries.[11] For this index, 0 represents full equality and 1 is total inequality, Japan places at 0.116 [10]. The GII measures three divisions: Reproductive Health, Empowerment and Labor Market. Japan is among the countries that equate closer towards the goal of full equality within the sub-set of countries considered to have high human development.[12]

The table shows Japan has areas of improvement. Japan severely lacks female voice in parliament even compared to similar Asian countries. Japan ranks as 4th lowest within the 51 highest developed countries. Another area Japan can improve upon is the female labor force, placing 6th lowest on that same scale. However, Japan ranks fairly well when it comes to adolescent birth rate and female population with some secondary education. Overall Japan is ranked among the countries with lowest GII because of its sharp performance of reproductive healthcare and the education that Japan allots the female population.[2]

Gender Roles through traditions and modern society in Japan

As work in progress is improving in Japan, an interesting fact in Japanese tradition has several gender roles when it comes to respecting traditional values. As the most common religion in Japan is Confucianism, its well known for covering the truth when it comes to foreign policies and scientific facts. When it comes to gender roles, it has a specific way of teaching Japanese boys and girls throughout their school years of how to be a boy and a girl. From dressing a certain way from head to toe to ways of how to blend in the community. Ways and boundaries to limit both men and women to be considered ‘normal’ in Japan. For instance, men from a young age were taught to be a successful person, get a higher education, to be the breadwinner of the family, and not disrespecting the family’s name. On the other hand, women were supposed to only receive education till middle school, or attend institutions on how to be a respectful wife and mother, learn to cook, clean, taking care of children, and most important of all, not allowed to work at all. It was not until 1900, that women were allowed to earn a college degree. However, as westernization and advancing technology getting more ‘developed’ in modern Japanese society, women now have more opportunities to change the trajectory of their lives. Instead of following their traditions of starting a family and clean for them, women now can choose to develop a career for themselves. But a price for freedom, the problem of the low birthrate in Japan,, women are often being accused of it. Nevertheless, as focusing on the timeline of women from life being chosen for them to choosing a life for themselves, on the other hand, men are still in the same position as it is in the past. Honoring their family’s name and always being the breadwinner of the family.

Gender Gap in Employment and Wages in Japan

Labor market segregation is associated with the gender wage gap. Occupational differences on gender in post World War II was the result of deliberate state policies to keep women from filling positions.[13]Recent research has also begun to show correlation between wages and gender segregation in employment. One explanation for the gender disparity in Japan is the crowding hypothesis. Haruhiko argues that this hypothesis pertains to full-time workers and states that as one occupation begins to build restrictions and barriers for women to apply and rightfully gain employment, the restricted job then hires primarily male workers causing women to find employment elsewhere, this in turn over-saturates non-restricted jobs with women.[14].

Findings have shown that the wages at the primarily male workplace will increase while the female abundant workplace(s) will see a wage decrease for both men and women. This hypothesis can only explain 5.1% of the total wage gap. The problem with the crowding hypothesis is that only ordinary full-time workers are used as a measure for this statistic. This percentage does not account for part time female workers who are stay at home mothers, post-married females or women who are forced to leave work because of child bearing.[14]

An alternative hypothesis called The Compensating Wage Differential hypothesis states that women are not forced into these jobs per se, but instead that they pick and choose their occupations based on the benefits package that each can provide. From work availability, to health compensation, women may choose to have a lower wage in order to have certain job benefits. This is proposed as another reason for the large wage gap that women in the Japanese economy face.[14] The study by Wei-hsin Yu shows that there is also a connection between wage raises if you are currently working in an environment that includes a majority of women. [15] Other theories include that of Sumiko Iwao who proposes that part-time work is also a choice for women in Japan in order to fulfill the duties expected of them at home[16].

The complete opposite of Iwao's theory is suggested by Mary Brinton who thinks that the government is structured around devices that disallow women to find "good jobs." Iwao focuses on culture while Brinton blames the economical systems Japan has in place.[16] The third key theory comes from Higuchi Keiko and she claims that gender diversification is due to public policy; political means.[16] Keiko justifies this through laws that the Japanese Government have set underlying policies that discretely favors gender diversification.[16] One such law pushed in the 1960's was called hitozukuri policy, or human-making policy.[16] This policy supported females with the responsibility to reproduce a new generation capable of economic success. It is through such policies that lead women to take certain roads during their career path.[16]

See also

- Gender Equality Bureau, Japan

- Family policy in Japan

- Feminism in Japan

- Kyariaūman, career woman

- Women in Japan

References

- ↑ “GDP per Capita by Countries, 2017.” Knoema, Knoema, knoema.com/atlas/ranks/GDP-per-capita?baseRegion=JP.

- 1 2 “Human Development Reports.” Human Development Reports, United Nations Development Program, 2017, hdr.undp.org/en/composite/GII.

- ↑ United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Gender Inequality Index (GII), accessed on 26th March 2018

- ↑ North, S. (2009). Negotiating What's 'Natural': Persistent Domestic Gender Role Inequality in Japan. Social Science Japan Journal, 12(1), 23-44. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/30209820

- 1 2 Ishii-Kuntz, M., Makino, K., Kato, K., & Tsuchiya, M. (2004). Japanese Fathers of Preschoolers and Their Involvement in Child Care. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(3), 779-791. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3600227

- 1 2 Baldwin, F., & Allison, A. (Eds.). (2015). Japan: The Precarious Future. NYU Press. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt15zc875

- 1 2 Nagase, N., & Brinton, M. (2017). The gender division of labor and second births: Labor market institutions and fertility in Japan. Demographic Research, 36, 339-370. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26332134

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hara, J. (2011). An Overview of Social Stratification and Inequality Study in Japan: Towards a 'Mature' Society Perspective. Asian Journal of Social Science, 39(1), 9-29. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43500535

- ↑ YAMADA, K. (2009). Past and Present Constraints on Labor Movements for Gender Equality in Japan. Social Science Japan Journal, 12(2), 195-209. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/40649682

- 1 2 Stephanie Assman, "Gender Equality in Japan: The Equal Employment Opportunity Law Revisited," The Asia Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 44, No. 2, November 10, 2014

- ↑ United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Gender Inequality Index (GII), accessed on 26th March 2018

- ↑ HDRO calculations based on data from UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Group (2013), UNDESA (2013a),IPU (2013), Barro and Lee (2013), UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2013) and ILO (2013a).

- ↑ Saakyan, A. R. (2014). JAPAN: GENDER INEQUALITY. Aziya i Afrika Segodnya, (11).

- 1 2 3 Hori, Haruhiko. 2009. “Labor market Segmentation and the Gender Wage Gap.”Japan Labor Review 6(1):5-20

- ↑ Yu, W. (2013). It's Who You Work With: Effects of Workplace Shares of Nonstandard Employees and Women in Japan. Social Forces, 92(1), 25-57. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/43287516

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Marchand, Marianne H. "Gender and Global Restructuring." Google Books, Routledge AUg. 2005, books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=XNOKKSrV1qIC&oi=fnd&pg=PA116&dq=division+of+labor+in+japan&ots=DKyJx0u4De&sig=EEM7nttYw_IJXCuOBiWS-m2rqUA#v=onepage&q=division%20of%20labor%20in%20japan&f=false