Frankfurt proposals

The Frankfurt proposals or Frankfurt memorandum was a Coalition peace initiative designed by Austrian minister Metternich. It was offered to French Emperor Napoleon I in November 1813 after he had suffered a decisive military defeat at the Battle of Leipzig. The goal was a peaceful end to the War of the Sixth Coalition. The Allies had reconquered most of Germany up to the Rhine, but they had not decided on the next step. Metternich took the initiative. The Allies, meeting in Frankfurt, drafted the proposals under Metternich's close supervision. The British diplomat in attendance, Lord Aberdeen, misunderstood London's position and accepted the moderate terms.[1][2]

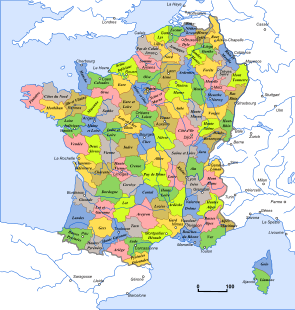

The proposal was that Napoleon would remain as Emperor of France, but France would be reduced to what the French revolutionaries claimed as France's "Natural borders." The natural borders were the Pyrenees mountains, the Alps mountains, and the Rhine River. France would retain control of Belgium, Savoy and the Rhineland (the west bank of the Rhine River), conquered and annexed during the early wars of the French Revolution, while giving up other conquests, including all of Spain, Poland and the Netherlands, and most of Italy and Germany east of the Rhine.[3]

Metternich and Napoleon, meeting privately at Dresden in June had already discussed the terms.[4] The final version was relayed to Napoleon by the Baron de Saint-Aignon in November.[5] Metternich told Napoleon these were the best terms the Allies were likely to offer; after further victories, the terms would become harsher and harsher. Metternich's motivation was to maintain France as a balance against Russian threats, while ending the highly destabilizing series of wars.[6][7]

Napoleon, expecting to win the war, delayed too long and lost this opportunity. By December Austria had signed treaties with the Allies, and London rejected the terms because they might allow Belgium to become a base for the invasion of England. The offer was withdrawn.[8] When the Allies invaded France in late 1813 Napoleon was heavily outnumbered; he tried to reopen peace negotiations on the basis of accepting the Frankfurt proposals.[9] The Allies now had new, harsher terms that included the retreat of France to its 1791 boundaries, which meant the loss of Belgium.[10] Napoleon adamantly refused. He was finally forced to abdicate on April 6, 1814 and lost his throne.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Henry A. Kissinger, A World Restored; Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-1822 (1957) pp 97-103

- ↑ Leggiere, Michael V. (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: Volume 1, The Allied Invasion of France, 1813-1814. Cambridge UP. pp. 42–62.

- ↑ Ross (1969), p 342

- ↑ Munro Price, "Napoleon and Metternich in 1813: some new and some neglected evidence," French History (2012) 26#4 pp 482-503.

- ↑ Robert Andrews, Napoleon: A Life (2014), pp 656-59, 685

- ↑ J. P. Riley (2013). Napoleon and the World War of 1813: Lessons in Coalition Warfighting. Routledge. p. 206.

- ↑ Leggiere (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: Volume 1, The Allied Invasion of France, 1813-1814. p. 53.

- ↑ Andrews, Napoleon: A Life (2014), p 686

- ↑ Riley (2013). Napoleon and the World War of 1813: Lessons in Coalition Warfighting. p. 206.

- ↑ Andrews, Napoleon: A Life (2014), p 695

Further reading

- Andrews, Robert. Napoleon: A Life (2014)

- Dwyer, Philip. Citizen Emperor: Napoleon in Power (2013) ch 22

- Dwyer, Philip G. "Self-Interest versus the Common Cause: Austria, Prussia and Russia against Napoleon," Journal of Strategic Studies (2008) 31#4 pp 605–632; explores why the Coalition held together so well in 1813-1814

- Esdaile, Charles. Napoleon's Wars: An International History 1803-1815 (2007) pp 217–18

- Kissinger, Henry A. A World Restored; Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace 1812-1822 (1957) pp 97–103

- Leggiere, Michael V. (2007). The Fall of Napoleon: Volume 1, The Allied Invasion of France, 1813-1814. Cambridge UP. pp. 42–62.

- J. P. Riley (2013). Napoleon and the World War of 1813: Lessons in Coalition Warfighting. Routledge. p. 206.

- Ross, Stephen T. European Diplomatic History 1789-1815: France against Europe (1969) pp 342–344

- Ward, A.W. and G. P. Gooch, eds. The Cambridge History of British Foreign Policy, 1783–1919: Volume I: 1783–1815 (1921) online pp 416–35;