Francis Grierson

| Francis Grierson | |

|---|---|

Grierson c. 1890 | |

| Born |

Benjamin Henry Jesse Francis Shepard September 18, 1848 Birkenhead, England |

| Died |

May 29, 1927 (aged 78) Los Angeles, California |

| Occupation | Composer, pianist, writer |

| Relatives | Benjamin Grierson (cousin) |

Benjamin Henry Jesse Francis Shepard (September 18, 1848 – May 29, 1927) was a composer, pianist, and writer who used the pen name of Francis Grierson.

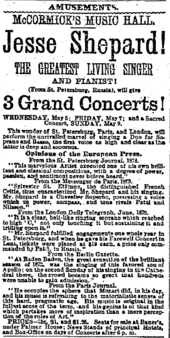

Early life and spiritualism

Jesse was born in Birkenhead, England,[1] to Joseph Shepard and Emily Grierson Shepard[2] and his family migrated to Illinois, United States while he was still a baby. Shepard traveled in Europe, finding audiences even among royalty, and impressed the French novelist Alexandre Dumas, fils. He was involved with Spiritualism and stated that many of his musical performances were the result of the spirits of famous composers channeling through him. Shepard traveled through California in 1876 performing at several of the old religious missions founded by the Spanish. He was invited to live in San Diego by a pair of real-estate developers, the High brothers, who enticed him by promising to build a mansion to his specifications. The result was the Villa Montezuma (named after "The Montezuma", a migrant ship that first brought Shepard to America).[3]

Tonner

In 1885, Shepard met Lawrence Waldemar Tonner, who became his friend and supporter for over 40 years. Tonner was born into the Danish Royal family in Thisted, Denmark on October 15, 1861. He emigrated to the U.S. through Glasgow, Scotland in 1870 and became a naturalized citizen of the U.S. in 1875, in Chicago, Illinois. He worked as a manager, press secretary, interpreter, French teacher, and as a translator and aide for Herbert Hoover.[4][5] Among the Waldemar Tonner Papers at ONE Archives, Los Angeles, is a letter recommending Tonner for a position with the Bureau of Public Information from Hoover, then head of the Food Administration. The letter was among Shepard's archived papers, which also included Tonner's credentials for the National Press Club of Washington, the Chevy-Chase Club and The University Club, Washington D.C., as well as Tonner's U.S. passport (issued in England by Robert Lincoln, son of the former president).[6] Tonner died on May 25, 1947 in Los Angeles, California, and is buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California.[5]

San Diego to Europe to Los Angeles

.jpg)

Despite his close association with Shepard, Tonner's name does not appear in the official documents by or about Shepard; for example, he is not listed in the San Diego City Directory as living at Villa Montezuma with Shepard.[4] The two shared the home from July 1887 to the third quarter of 1888, before taking a mortgage out on the property to fund an initial trip to Paris for the publishing of Shepard's first book. They returned to San Diego in August 1889, and on finding the city's economic boom had ended, sold the home and its furnishings by mid-December[7] before returning to Paris, where they lived until 1896.

After Paris, Shepard and Tonner settled in London until 1913, when they decided to return to the United States. In 1920, they settled in Los Angeles, which remained home for the rest of their lives.[8][9]

Final years and death

After years of traveling the world together, Shepard lost his popularity and Tonner supported him. He taught French and worked in a tailoring shop. Shepard died in Los Angeles on May 29, 1927, immediately after playing the last chord of a piano performance entertaining friends who had invited him to dinner; he was still upright with his hands on the keys and it was Tonner who first noticed that something was wrong. In newspaper announcements at the time of his death, it was noted that the once-successful Shepard had been living in poverty.[10] Shepard's body was cremated.[11][12]

Partial bibliography

- The Valley of Shadows

- Illusions and Realities of the War

- The Invincible Alliance and Other Essays (1913)

- Parisian Portraits

- The Humour of the Underman

- The Valley of Shadows

- La Vie et les hommes

- Abraham Lincoln, the Practical Mystic (1919)

- Modern Mysticism (1899)

- The Celtic Temperament (1901)

References

- ↑ Simpson, Herald P. (Summer 1961). "Francis Grierson: A Biographical Sketch and Bibliography" (PDF). Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1908–1984). University of Illinois Press. 54 (2): 198–203. JSTOR 40189785. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2010. Retrieved January 4, 2014.

- ↑ Crane, Clare (Spring–Summer 1987). Scharf, Thomas L., ed. "Jesse Shepard and the Spark of Genius". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego History Center. 33 (2 & 3). Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ↑ "A History of pianist, Spiritualist Jesse Shepard". villamontezumamuseum.org. Friends of the Villa Montezuma. Retrieved July 22, 2017.

- 1 2 Crane, Clare (Summer 1970). Freischlag, Linda, ed. "Jesse Shepard and the Villa Montezuma". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego History Center. 16 (3). Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- 1 2 McArron, Pat (June 22, 2012). "Lawrence Waldemar Tonner". Find a Grave.

- ↑ "MS 55 Jesse Shepard Papers". San Diego History Center (formerly San Diego Historical Society). Retrieved July 19, 2017.

- ↑ "A History of pianist, Spiritualist Jesse Shepard". villamontezumamuseum.org. Villa Montezuma Museum. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ Marble, Matt. "The Illusioned Ear: Disembodied Sound & The Musical Séances Of Francis Grierson". earwaveevent.org. Ear | Wave | Event. Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ Gaddis, Vincent H. (1994). "Mystery of the Musical Medium". Borderlands. Borderland Sciences Research Foundation. 50 (03). Retrieved July 16, 2017.

- ↑ "Francis Grierson Dies in Poverty". AP news. June 2, 1927. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ↑ "A History of author 'Francis Grierson'". villamontezumamuseum.org. Villa Montezuma Museum. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- ↑ McKinstry, DeeDee. "Jesse Shepard: The Man, the Myth, the Homeowner". sandiegohistory.org. San Diego Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

External links