History of USDA nutrition guides

The history of USDA nutrition guides includes over 100 years of American nutrition advice. The guides have been updated over time, to adopt new scientific findings and new public health marketing techniques. The current guidelines are the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015 - 2020. Over time they have described from 4 to 11 food groups.[1] Various guides have been criticized as not accurately representing scientific information about optimal nutrition, and as being overly influenced by the agricultural industries the USDA promotes.

Earliest guides

The USDA's first nutrition guidelines were published in 1894 by Dr. Wilbur Olin Atwater as a farmers' bulletin.[2][3] In Atwater's 1904 publication titled Principles of Nutrition and Nutritive Value of Food, he advocated variety, proportionality and moderation; measuring calories; and an efficient, affordable diet that focused on nutrient-rich foods and less fat, sugar and starch.[4][5] This information preceded the discovery of individual vitamins beginning in 1910.

A new guide in 1916, Food for Young Children by nutritionist Caroline Hunt, categorized foods into milk and meat; cereals; vegetables and fruits; fats and fatty foods; and sugars and sugary foods. How to Select Food in 1917 promoted these five food groups to adults, and the guidelines remained in place through the 1920s. In 1933, the USDA introduced food plans at four different cost levels in response to the Great Depression.[2]

In 1941, the first Recommended Dietary Allowances were created, listing specific intakes for calories, protein, iron, calcium, and vitamins A, B1, B2 B3, C and D.[2]

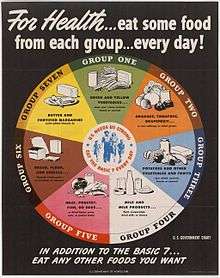

Basic 7

In 1943, during World War II, The USDA introduced a nutrition guide promoting the "Basic 7" food groups to help maintain nutritional standards under wartime food rationing.[6][7] The Basic 7 food groups were:

- Green and yellow vegetables (some raw; some cooked, frozen or canned)

- Oranges, tomatoes, grapefruit (or raw cabbage or salad greens)

- Potatoes and other vegetables and fruits (raw, dried, cooked, frozen or canned)

- Milk and milk products (fluid, evaporated, dried milk, or cheese)

- Meat, poultry, fish, or eggs (or dried beans, peas, nuts, or peanut butter)

- Bread, flour, and cereals (natural whole grain, or enriched or restored)

- Butter and fortified margarine (with added Vitamin A)

Basic Four

From 1956 until 1992 the United States Department of Agriculture recommended its "Basic Four" food groups.[8] These food groups were:

- Vegetables and fruits: Recommended as excellent sources of vitamins C and A, and a good source of fiber. Four or more servings from this group were recommended daily. Previous USDA food guides showed vegetables and fruits as unique groups, each with at least two recommended servings per day.

- Milk: Recommended as a good source of calcium, phosphorus, protein, riboflavin, and sometimes vitamins A and D. Cheese, ice cream, and ice milk could sometimes replace milk. Four servings from this group for teens and two for adults were recommended as a minimum daily.

- Meat: Two daily servings at least were recommended for protein, iron and certain B vitamins. Includes meat, poultry, fish, eggs, dry beans, dry peas, and peanut butter.

- Cereals and breads: Whole grain and enriched breads were especially recommended as good sources of iron, B vitamins and carbohydrates, as well as sources of protein and fiber. Includes cereals, breads, cornmeal, macaroni, noodles, rice and spaghetti. With the Basic Four daily food guide, the recommended minimum daily servings for the grains group doubled from two to four. Previously, in the Basic Seven guide, refined and non-enriched grains were included along with solid fats and sugar in a cluster of foods outside the essential seven.

"Other foods" were said to round out meals and satisfy appetites. These included additional servings from the Basic Four, or foods such as butter, margarine, salad dressing and cooking oil, sauces, jellies and syrups.[8]

The Basic Four guide was omnipresent in nutrition education in the United States.[9] A notable example is the 1972 series Mulligan Stew, providing nutrition education for schoolchildren in reruns until 1981.

Food Guide Pyramid

The introduction of the USDA's food guide pyramid in 1992 attempted to express the recommended servings of each food group, which previous guides did not do. 6 to 11 servings of bread, cereal, rice and pasta occupied the large base of the pyramid; followed by 3 to 5 servings of vegetables; then fruits (2 to 4); then milk, yogurt and cheese (2 to 3); followed by meat, poultry, fish, dry beans, eggs, and nuts (2 to 3); and finally fats, oils and sweets in the small apex (to be used sparingly). Inside each group were several images of representative foods, as well as symbols representing the fat and sugar contents of the foods.[10]

A modified food pyramid was proposed for adults aged over 70.[11] This "Modified Food Pyramid for 70+ Adults" accounted for changing diets with age by emphasizing water consumption as well as nutrient-dense and high-fiber foods.

Controversy

The first chart suggested to the USDA by nutritional experts in 1992 featured fruits and vegetables as the biggest group, not breads. This chart was overturned at the hand of special interests in the grain, meat, and dairy industries, all of which are heavily subsidized by the USDA.[12]

"The 'Pyramid' emphasized eating more vegetables and fruits, less meat, salt, sugary foods, bad fat, and additive-rich factory foods. USDA censored that research-based version of the food guide and altered it to include more refined grains, meat, commercial snacks and fast foods, only releasing their revamped version 12 years after it was originally scheduled for release. " [13]

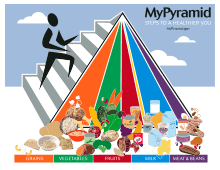

MyPyramid

In 2005, the USDA updated its guide with MyPyramid, which replaced the hierarchical levels of the Food Guide Pyramid with colorful vertical wedges, often displayed without images of foods, creating a more abstract design. Stairs were added up the left side of the pyramid with an image of a climber to represent a push for exercise. The share of the pyramid allotted to grains now only narrowly edged out vegetables and milk, which were of equal proportions. Fruits were next in size, followed by a narrower wedge for protein and a small sliver for oils. An unmarked white tip represented discretionary calories for items such as candy, alcohol, or additional food from any other group.[14]

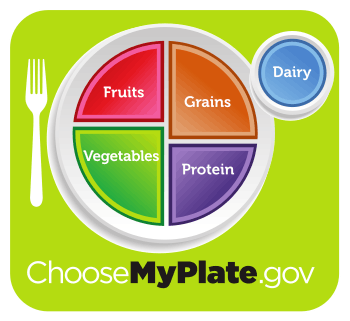

MyPlate

MyPlate is the current nutrition guide published by the United States Department of Agriculture,[15] consisting of a diagram of a plate and glass divided into five food groups. It replaced the USDA's MyPyramid diagram on June 2, 2011, ending 19 years of food pyramid iconography.[16] The guide will be displayed on food packaging and used in nutritional education in the United States.

Dietary Guidelines

The Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion in the USDA and the United States Department of Health and Human Services jointly released a longer textual document called Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015 - 2020, to be updated in 2020.[17] The first edition was published in 1980, and since 1985 has been updated every five years by the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee.[18] Like the USDA Food Pyramid, these guidelines have been criticized as being overly influenced by the agriculture industry.[19] These criticisms of the Dietary Guidelines arose due to the omission of high-quality evidence that the Public Health Service decided to exclude. The phrasing of recommendations was extremely important and widely affected everyone who read it. The wording had to be changed constantly as there were protests due to comments such as “cut down on fatty meats”, which led to the U.S Department of Agriculture having to stop the publication of the USDA Food Book. Slight alterations of various dietary guidelines had to be made throughout the 1970s and 1980s in an attempt to calm down the protests emerged. As a compromise, the phrase was changed to “choose lean meat” but didn’t result in a better situation.[20] In 2015 the committee factored in environmental sustainability for the first time in its recommendations.[21] The committee's 2015 report found that a healthy diet should comprise higher plant based foods and lower animal based foods. It also found that a plant food based diet was better for the environment than one based on meat and dairy.[22]

In 2013 and again in 2015, Edward Archer and colleagues published a series of research articles in PlosOne and Mayo Clinic Proceedings demonstrating that the dietary data used to develop the US Dietary Guidelines were physiologically implausible (i.e., incompatible with survival) and therefore these data were "inadmissible" as scientific evidence and should not be used to inform public policy.

In 2016, Nina Teicholz authored a critique of the US Dietary Guidelines in the British Medical Journal titled The scientific report guiding the US dietary guidelines: is it scientific? Teicholz suggested that "the scientific committee advising the US government has not used standard methods for most of its analyses and instead relies heavily on systematic reviews from professional bodies such as the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology, which are heavily supported by food and drug companies."

See also

References

- ↑ Nestle, Marion (2013) [2002]. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health. University of California Press. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-0-520-27596-6.

- 1 2 3 "Dietary Recommendations and How They Have Changed Over Time" (PDF). America's Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences. United States Department of Agriculture. May 1999. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ Atwater, W.O. (1894). "Farmers' Bulletin No. 23 - Foods : Nutritive Value and Cost". Internet Archive. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ "USDA Food Pyramid History". Healthy Eating Politics. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ "Principles of Nutrition and Nutritive Value of Food". Internet Archive. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ "Food Demonstrations To Be Held Over Nation". The Tuscaloosa News. The Associated Press. 2 April 1943. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ "To Demonstrate "Basic 7" Diet". The Free Lance-Star. Fredericksburg, Virginia. The Associated Press. 2 April 1943. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- 1 2 "The thing the professor forgot". National Agriculture Library Digital Repository. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

- ↑ Haddix, Carol (24 July 1985). "Four basic food groups grow up with the times". Evening Independent. St. Petersburg, Florida. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ Huston, Diane (29 April 1992). "Food guide pyramid is built on a base of grains". Daily News. Bowling Green, Kentucky. The Associated Press. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ Russell, Robert M.; Rasmussen, Helen; Lichtenstein, Alice H. (1999). "Modified Food Guide Pyramid for people over seventy years of age". The Journal of Nutrition. 129 (3): 751–753. PMID 10082784.

- ↑ "American Journal of Preventive Medicine" (PDF). 45 (3). September 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ Light, MS, EdD, Luise. "Biography". Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ↑ "MyPyramid -- Getting Started" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ "USDA's MyPlate". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ "Nutrition Plate Unveiled, Replacing Food Pyramid". The New York Times. 2 June 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ "Dietary Guidelines | Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion". Cnpp.usda.gov. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ↑ "2010 Dietary Guidelines For Americans" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 10, 2013. Retrieved July 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Internal Documents Reveal USDA Dietary Guidelines Panel Dominated by ADA". Business Wire. 2011-12-16. Retrieved 2016-10-12.

- ↑ Nestle, Marion. "USDA's Dietary Guidelines: Heath Goals Meets Politics" (PDF).

- ↑ Wheeler, Lydia (5 April 2015). "Vegan diet best for planet". thehill.com. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- ↑ Kleeman, Sophie (2015-04-07). "Government Report Confirms Vegan Lifestyle Really Is Better for Your Body and Your Planet". Mic. Retrieved 11 June 2015.