International aid to Palestinians

International aid has been provided to Palestinians since at least the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, following Israel's Declaration of Independence. It has played a major role in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict as the Palestinians claim it has been used as a means to keep the peace process going, and the Israelis that it is used to fund terrorism.[1] The Palestinian National Authority in the West Bank and Gaza Strip receives one of the highest levels of aid in the world. A dispute exists as to whether Palestinians or Israelis are the largest per capita beneficiaries of foreign aid.[2] Aid has been offered to the Palestinian National Authority (PA) and other Palestinian non-governmental organizations (PNGOs) by the international community, including international non-governmental organization (INGOs). In July 2018, Australia ceased providing direct aid to the PA, saying the donations could increase the PA's capacity to pay Palestinians convicted of politically motivated violence, and that it will direct its funds through United Nations programs.[3]

The entities that provide aid to the Palestinians are categorized into seven groups: the Arab nations, the European Union, the United States, Japan, international institutions (including agencies of the UN system), European countries, and other nations.[4]

UNRWA

UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) is a relief and human development agency which supports more than 5 million registered Palestinian refugees and their descendants, and other segments of Palestinian society, as well as providing some financial aid to Palestinians. Originally intended to provide jobs on public works projects and direct relief, today UNRWA provides education, health care, and social services to the population it supports. UNRWA employs over 30,000 staff, 99% of which are locally recruited Palestinians.[5] Most of UNRWA's funding comes from European countries and the United States. Between 2000 and 2015 the European Union had contributed €1.6 billion to UNRWA.[6]

In 2009, UNRWA's total budget was US$1.2 billion, for which the agency received US$948 million.[7] In 2009, the retiring Commissioner General spoke of a $200 million shortfall in UNRWA's budgets.[8] Officials in 2009 spoke of a 'dire financial crisis'.[9]

In 2010, the biggest donors for its regular budget were the United States and the European Commission with $248 million and $165 million respectively. Sweden ($47m), the United Kingdom ($45m), Norway ($40m), and the Netherlands ($29m) are also important donors.[10] In addition to its regular budget, UNRWA receives funding for emergency activities and special projects.

In 2011, the United States was the largest single donor with a total contribution of over $239 million, followed by the European Commission's $175 million contribution.[11]

According to World Bank data, for all countries receiving more than $2 billion international aid in 2012, Gaza and the West Bank received a per capita aid budget over double the next largest recipient, at a rate of $495.[12][13]

In 2013, $1.1 billion was donated to UNRWA,[14] of which $294 million was contributed by the United States,[15] $216.4 million from the EU, $151.6 million from Saudi Arabia, $93.7 million from Sweden, $54.4 million from Germany, $53 million from Norway, $34.6 million from Japan, $28.8 million from Switzerland, $23.3 million from Australia, $22.4 million from the Netherlands, $20 million from Denmark, $18.6 million from Kuwait, $17 million from France, $12.3 million from Italy, $10.7 million from Belgium as well as $10.3 million from all other countries.[16]

In 2016, the United States donated $368 million to the agency, and $350 million in 2017, but has cut around one third of its contributions for 2018.[17] In January 2018, the United States withheld $65 million, roughly half the amount due in the month, again creating a financial crisis for UNRWA.[18] Belgium and Netherlands plan to increase their contributions to UNRWA.[17]

History

Before Oslo Accords

Before the signing of the Oslo Accords, international aid for the West Bank and Gaza came mainly from Western and Arab states, mostly through UN agencies such as UNRWA. Most programs were started or developed during the 1970s, and expanded during the 1980s. Most of the aid was channeled through PNGOs or INGOs.[19] Although the stance of the donors during the pre-Oslo period is regarded by some analysts, such as Rex Brynen, as controversial and linked with phenomena such as corruption, nationalism and factional rivalries,[20] international aid effectively financed a series of programs in the sectors of agriculture, infrastructure, housing and education.[21]

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords, officially signed[22] on September 13, 1993, contained substantial provisions on economic matters and international aid: Annex IV of the Declaration of Principles (DoP) discusses regional cooperation and implicitly calls for major international aid efforts to help the Palestinians, Jordan, Israel and the entire region.[23]

On October 1, 1993, the international donor community (nations and institutions[24]) met in Washington to mobilize support for the peace process, and pledged to provide approximately $2.4 billion to the Palestinians over the course of the next five years.[25] The international community's action was based on the premise that it was imperative to garner all financial resources needed to make the agreement successful, and with a full understanding that in order for the Accords to stand in the face of daily challenges on the ground, ordinary Palestinians needed to perceive positive change in their lives.[26] Therefore, the donors had two major goals: to fuel Palestinian economic growth and to build public support for negotiations with Israel.[27] According to Scott Lasensky, "throughout the follow-up talks to the DoP that produced the Gaza-Jericho Agreement (May 1994), the Early Empowerment Agreement (August 1994), the Interim Agreement (September 1995), and the Hebron Accord (January 1997), [...] economic aid hovered over the process and remained the single most critical external component buttressing the PNA."[28]

1993–2000

Between 1993 and 1997 the PNA faced serious economic and financial problems.[29] International aid prevented the collapse of the local economy, and contributed to the establishment of the Palestinian administration.[30] Donors' pledges continued to increase regularly (their value had risen to approximately $3,420 million as of the end of October 1997) as a result of the faltering peace process, along with the increase in needs and the consequent increase in the assistance necessary for Palestinians to survive.[31] Reality led, however, to a revision of the donors' priorities:[32] Out of concern that the deteriorating economic conditions could result in a derailment of the peace process, donor support was redirected to finance continued budgetary shortfalls, housing programs and emergency employment creation.[33] According to a more critical approach, international aid in the mid-1990s supported PNA's bureaucracy[34] and belatedly promoted the centralization of political power, but in a way that did not enhance government capacity and harmed the PNGOs.[35] In 1994–1995 problems of underfunding, inefficiency and poor aid coordination marked donors' activity, and led to tensions among the different aid bodies, and between the international community and the PNA.[36] In 1996, the link between development assistance and the success of the peace process was made explicit by the President of the World Bank, James Wolfensohn, who stated: "The sense of urgency is clear. Peace will only be assured in that area if you can get jobs for those people."[37]

After 1997, there was a reduction in the use of closure policy by Israel, which led to an employment growth and an expansion of the West Bank and Gaza economy.[38] After the signing of the Wye River Memorandum, a new donors' conference was convened, and over $2 billion was pledged to the PNA for 1999–2003.[39] Nevertheless, overall donor disbursements fell in 1998–2000, and the 1998 disbursements=to-commitments ratio was the lowest since 1994.[40] As for international institutions, they began to play a bigger role in the international funding process, in spite of the decline in the absolute value of these institutions' total commitments.[41] After 1997, the need for donor support for the current budget and employment generation programs receded due to the PA's improved fiscal performance, and attention was focused instead on infrastructures to the detriment of institution building.[40] Donors' activity was also characterized by a decline in support for PNGOs, and by a preference to concessionary loans (instead of grants) with generous grace periods, long repayment periods and low interest rates[42]

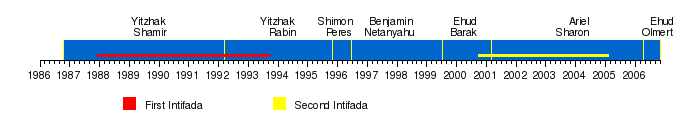

2000–06

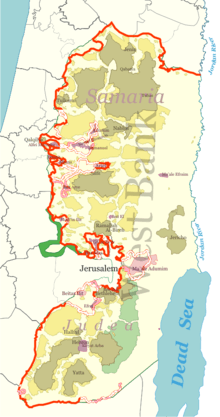

The second Intifada led to one of the deepest recessions the Palestinian economy experienced in modern history.[43] In those two years, Palestinian real GDP per capita shrunk by almost 40 percent.[44] The precipitator of this economic crisis was again a multi-faceted system of restrictions on the movement of goods and people designed to protect Israelis in Israel itself and in the settlements.[43]

One of the many frustrations of the crisis was the erosion of the development effort financed by the international community, since the overwhelming emphasis in donor work was now directed towards mitigating the impact of the economic and social crisis. A collapse of the PNA was averted by emergency budget support from donor countries. Despite a significant increase in donor commitments in 2002 compared with 2001, commitments to infrastructure and capacity-building work with a medium-term focus continued to decline. In 2000, the ratio was approximately 7:1 in favor of development assistance. By 2002, the ratio had shifted to almost 5:1 in favor of emergency assistance.[45]

Yasser Arafat's death in 2004 and Israel's unilateral disengagement from Gaza created new hopes to the donor community. In March 2005, the Quartet on the Middle East underscored the importance of development assistance, and urged the international donors community to support Palestinian institution building,[46] without however ignoring budgetary support.[47] The Quartet also urged Israel and the PNA to fulfill their commitments arising from the Road map for peace, and the international community "to review and energize current donor coordination structures [...] in order to increase their effectiveness."[46] The international community's attempt in late 2005 to promote Palestinian economic recovery reflected a long-standing assumption that economic development is crucial to the peace process and to prevent backsliding into conflict.[48] Although a mild positive growth returned in 2003 and 2005, this fragile recovery stalled as a result of the segmentation of the Gaza Strip, the stiff restrictions on movements of goods and people across the borders with Israel and Egypt, and the completion of the Israeli West Bank barrier.[49] As the World Bank stressed in December 2005, "growth will not persist without good Palestinian governance, sound economic management and a continued relaxation of closure by GOI."[50]

2006–07

On 25 January 2006, the Islamist organization, Hamas, which is considered by the main donor countries to be a terrorist organization, won the Palestinian legislative elections and formed government on 29 March 2006, without accepting the terms and conditions set by the Quartet.[51] This resulted in the imposition of economic sanctions against the PA, including near cessation of direct relations and aid between most bilateral donors and the PA, with only some multilateral agencies and a few donors continuing direct contact and project administration.[52] The Quartet's decision was criticised by the Quartet's former envoy, James Wolfensohn, who characterized it "a misguided attempt to starve the Hamas-led Palestinians into submission," and of UN's Middle East former envoy, Alvaro de Soto.[53]

Because of the worsening humanitarian crisis, the EU proposed a plan to channel aid directly to the Palestinians, bypassing the Hamas-led government. The Quartet approved the EU proposal, despite an initial US objection, and the EU set up a "temporary international mechanism" (TIM) to channel funds through the Palestinian President for an initial period of three months, which was later extended.[54] Oxfam was one of the main critics of the EU TIM program arguing that "limited direct payments from the European Commission have failed to address this growing crisis."[55]

The emergence of two rival governments in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip in June 2006 presented the international community with the prospect of shouldering a huge aid burden.[56] The World Bank estimated that in 2008 PNA would need $1.2 billion in recurrent budget support, in addition to $300 million in development aid.[57] The formation of the caretaker government in mid-2007 in the West Bank led by Salam Fayyad, led to the resumption of aid to the West Bank PA government which partly reversed the impact of the aid boycott.[58] Nevertheless, economic indicators have not changed considerably. For instance, because of the situation in Gaza, real GDP growth was estimated to be about -0.5% in 2007, and 0.8% in 2008.[59]

According to the Development Assistance Committee, the main multilateral donors for the 2006–2007 period were UNRWA and the EU (through the European Commission); the main bilateral donors were the US, Japan, Canada and five European countries (Norway, Germany, Sweden, Spain and France).[60]

2007–09

| Paris pledging conference, 2007[61] | |

|---|---|

| Type of assistance | US$ billion |

| Budget support | 1.5 |

| Humanitarian assistance | 1.1 |

| Project-based aid | 2.1 |

| Other aid | 0.8 |

| Amounts being allocated | 2.2 |

| Total 2008–2010 | 7.7 |

In December 2007, during the Paris Conference, which followed the Annapolis Conference, donor countries pledged over $7.7 billion for 2008–2010 in support of the Palestinian Reform and Development Program (PRDP).[61] Hamas, which was not invited to Paris, called the conference a "declaration of war" on it.[62] In the beginning of 2008, the EU moved from the TIM mechanism to PEGASE, which provided channels for direct support to the PA's Central Treasury Account in addition to the types of channels used for TIM. The World Bank also launched a trust fund that would provide support in the context of the PA's 2008–2010 reform policy agenda.[63] However, neither mechanism contained sufficient resources to cover the PA's entire monthly needs, thus not allowing the PA to plan expenditures beyond a two-month horizon.[64]

The World Bank assesses that the PA had made significant progress on implementing the reform agenda laid out in the PRDP, and re-establishing law and order. Gaza, however, remained outside the reforms as Hamas controls security and the most important ministry positions there. Palestinian inter-factional tension continued in the West Bank and Gaza, with arrests of people and closures of NGOs by each side, resulting in a deterioration in the ability of civil society organizations to continue to cater to vulnerable groups.[65] Following the 2008–2009 Israel–Gaza conflict, an international conference took place in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, where donors pledged almost $4.5 billion for the reconstruction of Gaza. These funds bypassed Hamas, since the PA in collaboration with the donor community has taken the lead in delivering and distributing the assistance.[66] India which is aspiring to be recognized as 'globally respected power' has made concerted efforts in fostering better relations with the PA. When PA President Abbas visited New Delhi in 2008 he was offered a credit of US$20 million (Rs.900 million) by the Indian government. India also continued to offer eight scholarships under ICCR Schemes to Palestinian students for higher studies in India, while also offering several slots for training courses under the ITEC Program.

According to estimates made by the World Bank, the PA received $1.8 billion of international aid in 2008 and $1.4 billion in 2009.[67]

2010

In 2010, the lion's share of the aid came from the European Union and the United States. According to estimates made by the World Bank, the PA received $525 million of international aid in the first half of 2010.[67] Foreign aid is the "main driver" of economic growth in the Palestinian territories.[67] According to the International Monetary Fund, the unemployment rate has fallen as the economy of Gaza grew by 16% in the first half of 2010, almost twice as fast as the economy of the West Bank.[68]

In July 2010, Germany outlawed a major Turkish-German donor group, the Internationale Humanitaere Hilfsorganisation (IHH) (unaffiliated to the Turkish İnsani Yardım Vakfı (İHH))[69] that sent the Mavi Mamara aid vessel, saying it had used donations to support projects in Gaza that are related to Hamas, which is considered by the European Union to be a terrorist organization,[70][71] while presenting their activities to donors as humanitarian help. German Interior Minister Thomas de Maiziere said, "Donations to so-called social welfare groups belonging to Hamas, such as the millions given by IHH, actually support the terror organization Hamas as a whole."[70][71]

2011

In March 2011, there were threats to cut off aid to the PA if it continued to move forward on a unity government with Hamas, unless Hamas formally renounced violence, recognized Israel, and accepted previous Israel-Palestinian agreements.[72] Azzam Ahmed, spokesman for PA President Abbas, responded by stating that the PA was willing to give up financial aid in order to achieve unity, "Palestinians need American money, but if they use it as a way of pressuring us, we are ready to relinquish that aid."[73]

2014

In October 2014, the Cairo Conference on Palestine, an international donor conference on reconstructing the Gaza Strip, garnered $5.4 billion in pledges, of which $1 billion was pledged by Qatar. Half of the pledges were to be used for rebuilding efforts in Gaza, while the remainder was to support the PA budget until 2017.[74]

2018

On 23 March 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump signed the Taylor Force Act into law, which will cut about a third of US foreign aid payments to the PA,[75] until the PA ceases making payment of stipends to terrorists and their surviving families.[76][77]

In July 2018, Australia stopped the A$10M (US$7.5M) in funding that had been sent to the PA via the World Bank, and instead is sending it to the UN Humanitarian Fund for the Palestinian Territories. The reason given was that they did not want the PA to use the funds to assist Palestinians convicted of politically motivated violence.[78]

On 24 August, the United States cut more than $200 million in aid to the PA.[79]

Major donors

Since 1993 the European Commission and the EU member-states combined have been by far the largest aid contributor to the Palestinians.[80]

Arab League states have also been substantial donors, notably through budgetary support of the PNA during the Second Intifada. However, they have been criticized for not sufficiently financing the UNRWA and the PNA, and for balking at their pledges.[81] After the 2006 Palestinian elections, the Arab countries tried to contribute to the payment of wages for Palestinian public servants, bypassing the PNA. At the same time Arab funds were paid directly to Abbas' office for disbursement.[82]

During the Paris Conference, 11% of the pledges came from the US and Canada, 53% from Europe and 20% from Arab countries.[61]

Structure

Donor coordination

Since 1993, a complex structure for donor coordination has been put in place in an effort to balance competing American and European positions, facilitate agenda-setting, reduce duplication, and foster synergies.[83] The overall monitoring of the donors' activities was assigned to the Ad-Hoc Liaison Committee, which was established in November 1993, operates on the basis of consensus, and aims at promoting the dialogue between the partners of the "triangular partnership", namely the donors, Israel, and the PNA.[84]

Human rights organizations concerns

June 2016, Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Monitor has released a report discussing the Israel’s repetitive destruction of EU-funded projects in Palestine. The report "squandered aid" claimed that, since 2001, Israeli authorities have destroyed around 150 development projects, which incurs the EU a financial loss of approximately €58 million. The report estimated the total value of EU squandered aid money, including development and humanitarian projects, amounts to €65million—of which at least €23million were lost during the 2014 assault alone. The Monitor called for investigation on all destruction structures built with funding from the UN, EU or member states on Palestinian land. In addition, the monitor recommended to continue investing in Palestinian development, but substantively penalize the Israeli government when UN- or European-funded projects are targeted.[85]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Keating (2005), 2

- ↑ Palestine Human Development Report (2004), 113. According to certain analyses, Palestinians are the largest per capita recipients of international development assistance in the world (Lasensky [2004], 211, Lasensky-Grace [2006] Archived December 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.). Hever (2005), 13, 16 Archived October 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., and (2006), 5, 10 refutes this assessment, arguing that Israel is the biggest recipient of total foreign aid in the world. Turner (2006), 747, underscores that the US provides Israel with annual bilateral funds of US$654 per person, which is more than double what the Palestinians receive in multilateral aid. According to Le More (2005), 982, "the United States has also provided [the PNA with] considerable funds, even if they are negligible compared to what it allocates bilaterally to Israel—which alone far exceeds the level of combined international assistance to the Palestinians."

- ↑ Australia diverts Palestinian money amid fears of support for terrorists

- ↑ Palestine Human Development Report (2004), 116 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ UNRWA In Figures

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-07-20. Retrieved 2015-06-07.

- ↑ UNRWA. "Frequently Asked Questions". Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ↑ "'Sounds worrying'". Al Ahram weekly. 2009-04-09. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- ↑ "Employees of UN agency for Palestinian refugees on strike". Relief Web citing an AFP report. 2009-11-17. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-14.

- ↑ UNRWA. "Financial updates". Retrieved 2011-09-25.

- ↑ "Palestinian kids taught to hate Israel in UN-funded camps, clip shows".

- ↑ "Net official development assistance (ODA) per capita for countries receiving over $2 billion in 2012, latest World Bank figures published in 2014". World Bank. 2014-08-15. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ "World Development Indicators: Aid dependency Table of all countries". World Bank. 2014-08-15. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ "Search UNRWA".

- ↑ Sadallah Bulbul (19 March 2014). "TOP 20 DONORS TO UNRWA IN 2013" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-06. Retrieved 2014-09-14.

- 1 2 Belgium, Netherlands to supplement UNRWA funds cut by U.S.

- ↑ "UN Palestinian aid agency says US cuts spark worst-ever financial crisis". CNN. January 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Since 1970 the role of the INGOs (and in particular of the Northern NGOs) in the delivery of aid was strengthened. (Hanafi-Tabar [2005], 35–36).

- ↑ For instance, Jordan's disengagement from its administrative role in the West Bank just after 1990, and the discontent of some Arab states-donors for the Palestine Liberation Organization's stance during the First Gulf War resulted in the Organization's almost complete breakdown (Brynen [2000], 47–48).

- ↑ Brynen (2000), 44–48

- ↑ Before the signing ceremony, President Bill Clinton and Secretary of State Warren Christopher spoke in very clear terms about America's commitment to provide economic support to the Palestinians. Israeli foreign minister Shimon Peres told Palestinian officials that he had already secured commitments from European countries to give them aid (Lasensky [2002], 93 Archived November 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. and [2004], 219).

- ↑ Annex IV (paragraph 1) of the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements Archived October 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.: "The two sides will cooperate in the context of the multilateral peace efforts in promoting a Development Program for the region, including the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, to be initiated by the G7. The parties will request the G7 to seek the participation in this program of other interested states, such as members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, regional Arab states and institutions, as well as members of the private sector."

- ↑ 22 donor states, major international financial institutions, and states neighboring the West Bank and Gaza (Frisch-Hoffnung [1997], 1243).

- ↑ Aid Effectiveness (1999), 11; An Evaluation of Bank Assistance (2002), 2 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.; Palestine Human Development Report (2004), 115 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Palestine Human Development Report (2004), 113 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Lasensky-Grace (2006) Archived October 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.. According to Yezid Sayigh (2007), 9, "starting with the first international donor conference in October 1993, foreign aidwas intended to demonstrate tangible peace dividends to the Palestinians as well as provide economic reconstruction and development to build public support for continued diplomacy.

- ↑ Lasensky (2002), 94 Archived November 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. and (2004), 221

- ↑ Poor economic performance in these years was the product of many factors, such as the low public investment and the contraction of the regional economy, and they were aggravated by the effects of Israeli closures, permits policies, and other complex restrictions on the movement of people and goods (Aid Effectiveness [1999], 15 Archived June 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.; Brynen [2000], 64; Le More [2005], 984).

- ↑ An Evaluation of Bank Assistance (2002), 24 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.; Rocard (1999), 28; Roy (1995), 74–75

- ↑ Palestine Human Development Report (2004), 115 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ As USAID director Chris Crowley stated, "the political situation often drove the aid disbursement process (Lasensky [2002], 96–97 Archived November 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.)."

- ↑ An Evaluation of Bank Assistance (2002), 25 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.; Brynen-Awartani-Woodcraft (2000), 254

- ↑ According to Brynen (2005), 228, "closure [...] exacerbated the tendency of the PNA to use public sector employment as a tool of both political patronage and local job creation. The public sector payroll thus continued to expand at a rapid rate, growing from 9% of GDP in 1995 to 14% by 1997 [...] This sapped public funds needed for investment purposes and threatened to outstrip fiscal revenues."

- ↑ Frisch-Hoffnung (1997), 1247–1250

- ↑ The Palestinians construed the shortage of aid funding as a form of punishment and as attempt of the donors to impose their own agenda, while US officials blamed "intra-PLO politics, the Palestinian leadership's resistance to donors' standards of accountability, and inexperienced [middle] management (Ball-Friedman-Rossiter [1997], 256; Brynen [2000], 114; Brynen-Awartani-Woodcraft [2000], 222; Lasensky [2004], 223; Roy [1995], 74–75)."

- ↑ Ball-Friedman-Rossiter (1997), 257

- ↑ GDP grew by an estimated 3.8% in 1998 and 4.0% in 1999, and unemployment fell to 12.4 percent in 1999, almost half its 1996 peak (Aid Effectiveness [1999], 14).

- ↑ Lasensky (2002), 98 Archived November 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.; Lasensky (2004), 225; Rocard(1998), 28

- 1 2 Donor Disbursements and Public Investment Archived December 18, 2005, at the Wayback Machine., UNSCO

- ↑ Palestine Human Development Report (2004), 117 Archived August 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Aid Effectiveness (1999), 18–20; Brynen (2000), 74; UNCTAD (2006), 18 Archived December 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Disengagement (2004), 1 Archived June 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Overview (2004), 6 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Twenty-Seven Months (2003), 51 Archived March 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Quartet Statement - London, March 1, 2005 Archived August 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Jerusalem Media and Communication Center

- ↑ As Rodrigo de Rato stated, "substantial external budget assistance is necessary to allow the PNA to continue to function and mobilize political support."

- ↑ Sayigh (2007), 9

- ↑ According to the World Bank, "the incompatibility of GOI's continuous movement proposal with donor and PA funding criteria, allied with GOI's commitment to protecting access to Israeli settlements, translate to a continuing high level of restriction on Palestinian movement throughout much of the West Bank (Overview [2004], 6, 9 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.)."

- ↑ The Palestinian Economy (2005), 1–2 Archived March 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ According to the Quartet Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., "all members of the future Palestinian government must be committed to non-violence, recognition of Israel and acceptance of previous agreements and obligations, including the roadmap."

- ↑ Sayigh (2007), 17; Two Years after London (2007), 30 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Eldar, Quartet to Hold Key Talks Archived May 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.; McCarthy-Williams, Secret UN report condemns US Archived April 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.; McCarthy-Williams, UN Was Pummeled into Submission Archived March 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ US "Blocks" Palestinian Aid Plan Archived January 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., BBC News; Powers agree Palestinian Aid Plan Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., BBC News; Palestinians to Get Interim Aid Archived August 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., BBC News

- ↑ Oxfam, EU Must Resume Aid Archived October 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.; Oxfam, Middle East Quartet Archived June 22, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.. According to the International Federation for Human Rights, 7 Archived September 21, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., "the temporary international mechanism (TIM) did not make up for the impact of the sanctions, because it did not allow for the payment of the wages of Palestinian civil servants."

- ↑ Sayigh (2007), 27

- ↑ Thus, external aid will be at least 32% of GDP (Palestinian Economic Prospects [2008], 7 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.).

- ↑ The Bush administration unfroze $86 million in August 2007; the first $10 million was intended to strengthen Mr. Abbas' security forces (Cooper-Erlanger, Rice Backs Appointed Palestinian Premier).

- ↑ Implementing the Palestinian Reform (2008), 6 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.; Palestinian Economic Prospects (2008), 6–7 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Palestinian Adm. Areas Archived February 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., DAC-OECD

- 1 2 3 Implementing the Palestinian Reform (2008), 10 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Palestinians "Win $7bn Aid Vow" Archived August 8, 2016, at the Wayback Machine., BBC News

- ↑ Implementing the Palestinian Reform (2008), 15 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.; Overview of PEGASE Archived March 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., European Commission

- ↑ Palestinian Economic Prospects (2008), 35 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Palestinian Economic Prospects (2008), 5–6 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Fund-Channeling Options (2009), 6; Pleming & Sharp, Donors Pledge £3.2 billion for Gaza

- 1 2 3 David Wainer "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-12-12. Retrieved 2010-12-08. "Palestinians Lure Banks With First Sukuk Bills: Islamic Finance," December 08, 2010, Bloomberg/Business Week

- ↑ [Hamas and the Peace Talks,"] The Economist, September 25, 2010, p. 59.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-16. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- 1 2 Germany outlaws IHH over claimed Hamas links, Haaretz 12.07.10

- 1 2 Germany bans group accused of Hamas links, Ynet 07.12.10 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Herb Keinon and Khaled Abu Toameh, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2011-03-29. 'J'lem to cut ties with PA if Hamas added to unity gov't', March 27, 2011, Jerusalem Post

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-10-23. Retrieved 2011-03-29. 'Abbas would give up US aid to reconcile with Hamas' March 28, 2011, Jerusalem Post.

- ↑ Michael R. Gordon (October 12, 2014), Conference Pledges $5.4 Billion to Rebuild Gaza Strip, The New York Times.

- ↑ "Taylor Force Becomes Law". The New York Sun. 23 March 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ Tubbs, Ashlyn (28 September 2016). "Senators introduce Taylor Force Act to cut terror attack funding". KCBD. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ↑ "Pay for Slay in Palestine U.S. aid becomes a transfer payment for terrorists". Wall Street Journal. 27 March 2017. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ "Reallocation of aid to the Palestinian Authority". Australia Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. 2 July 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ↑ TRUMP CUTS $200 MILLION IN AID TO PALESTINIANS

- ↑ Le More (2005), 982

- ↑ At Riyadh Summit Archived February 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., Associated Press; Freund, Do Arab States really Care about the Palestinians? Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.; Rubin (1998) Archived March 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Two Years after London (2007), 30 Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Aid Effectiveness (1999), 34; Le More (2004), 213

- ↑ Brynen (2002), 92; Lasensky-Grace (2006) Archived October 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.; Le More (2004), 213

- ↑ Monitor, Euro-Med. "Squandered Aid: Israel's repetitive destruction of EU-funded projects in Palestine". Retrieved 2016-08-22.

References

- Aid Effectiveness in the West Bank and Gaza. Japan and the World Bank. 1999.

- "At Riyadh Summit, Arab States to Propose Increasing Aid to PA". The Associated Press. March 25, 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- Ball, Nicole; Friedman, Jordana D.; Rossiter, Caleb S. (2000). "The Role of International Financial Institutions in Preventing and Resolving Conflict". In David Cortright. The Proce of Peace: Incentives and International Conflict Prevention. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-8557-8.

- Brynen, Rex (2000). A very Political Economy: Peacebuilding and Aid in the West Bank and Gaza. Washington: United States Institute of Peace. ISBN 1-929223-04-8.

- Brynen, Rex (2005). "Donor Assistance"Lessons from Palestine for Afghanistan". In Gerd Junne; Willemijn Verkoren. Postconflict Development: Meeting New Challenges. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-58826-303-7.

- Brynen, Rex; Awartani, Hisham; Woodcraft, Clare (2000). "The Palestinian Territories". In Shepard Forman; Stewart Patrick. Good Intentions: Pledges of Aid for Postconflict Recovery. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 1-55587-879-2.

- Cooper, Helene; Erlanger, Steven (August 3, 2007). "Rice Backs Appointed Palestinian Premier and Mideast Democracy". Middle East. New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- "Criteria Set for Palestinian Aid". BBC News. January 31, 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- "Disengagement, the Palestinian Economy and the Settlements" (PDF). World Bank. June 23, 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 7, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- "Donor Disbursements and Public Investment". Report on the Palestinian Economy. UNSCO. Autumn 1999. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- Eldar, Akiva (March 3, 2006). "Quartet to Hold Key Talks on Fate of its Mideast Peacemaking Role". Haaretz. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- "EU Must Resume Aid to Palestinian Authority". Oxfam International. September 14, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- "Failing the Palestinian State, Punishing its People" (PDF). International Federation for Human Rights. October 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- Freund, Michael (February 9, 2007). "Do Arab States really Care about the Palestinians?". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- Frisch, Hillel; Hofnung, Menachem (1997). "State Formation and International Aid: The Emergence of the Palestinian Authority". World Development. 25 (8): 1243–1255. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(97)00028-4.

- "Fund-Channeling Options For Early Recovery and beyond" (PDF). World Bank. March 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

- Hanafi, Sari; Tabar, Linda (2005). The Emergence of a Palestinian Globalized Elite - Donors, International Aid and Local NGOs. Jerusalem: The Institute for Palestinian Studies and Muwatin, the Palestinian Institute for the Study of Democracy. ISBN 9950-332-00-1.

- Hever, Shir (April–May 2005). "Do Palestinians Get the Most Foreign Aid in the World?". Palestine/Israel: News within/from. 21 (3): 13–17. Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on October 31, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- Hever, Shir (2006). The Economy of the Occupation: Foreign Aid to Palestine-Israel (PDF). Jerusalem: The Alternative Information Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-27.

- "Implementing the Palestinian Reform and Development Agenda" (PDF). World Bank. May 2, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- Keating, Michael (2005). "Introduction". In Michael Keating; Anne Le More; Robert Lowe. Aid, Diplomacy and Facts on the Ground. London-Washington: Chatham House – Royal Institute of International Affairs. ISBN 1-86203-164-9.

- Lasensky, Scott (2004). "Paying for Peace: The Oslo Process and the Limits of American Foreign Aid" (PDF). Middle East Journal. 58 (2): 210–234. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-06-23. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- Lasensky, Scott (March 2002). "Underwriting Peace in the Middle East: US Foreign Policy and the Limits of Economic Inducements" (PDF). Middle East Review of International Affairs. 6 (1): 89–105. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- Lasensky, Scott; Grace, Robert (August 2006). "Dollars and Diplomacy: Foreign Aid and the Palestinian Question". USIPeace Briefing. United States Institute of Peace. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- Le More, Anne (2004). "Foreign Aid Strategy". In Cobham, David P. The Economics of Palestine. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32761-X.

- Le More, Anne (October 2005). "Killing with Kindness:Funding the Demise of a Palestinian State". International Affairs. 81 (5): 981–999. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00498.x. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- McCarthy, Rony; Williams, Ian (June 13, 2007). "Secret UN Report Condemns US for Middle East Failures". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- McCarthy, Rony; Williams, Ian (June 13, 2007). "UN was Pummelled into submission, Says Outgoing Middle East Special Envoy". guardian.co.uk. Retrieved 2008-06-28.

- "Middle East Quartet Should End Palestinian Authority Aid Boycott and Press Israel to Release Confiscated Taxes". Oxfam GB. February 21, 2007. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- "Overview: Stagnation or Revival? Israeli Disengagement and Palestinian Economic Prospects" (PDF). World Bank. December 1, 2004. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- "Overview of Pegase". European Commission Technical Assistance Office for the West Bank & Gaza Strip. Archived from the original on 2009-03-22. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- Palestine Human Development Report (PDF). Ramallah-Gaza: Birzeit University - Development Studies Program. 2004. ISBN 9950-334-01-2.

- "Palestinian Adm. Areas". Development Assistance Committee. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- "Palestinian Economic Prospects: Aid, Access and Reform" (PDF). World Bank. September 22, 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-21.

- "Palestinians to Get Interim Aid". Middle East. BBC News. May 10, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- "Palestinians Win "$7bn Aid Vow"". Middle East. BBC News. December 17, 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

- Pleming, Sue; Sharp, Alastair (March 3, 2009). "Donors Pledge £3.2 billion for Gaza". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- "Powers Agree Palestinian Aid Plan". Middle East. BBC News. June 18, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- "Quartet Statement – London". Jerusalem Media and Communication Center. March 1, 2005. Archived from the original on August 15, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- Rocard, Michel (1999). "International Donor Community". Strengthening Palestinian Public Institutions. Council on Foreign Relations. ISBN 0-87609-262-8.

- Roy, Sara (Summer 1995). "Alienation or Accommodation". Journal of Palestinian Studies. 24 (4): 73–82. doi:10.1525/jps.1995.24.4.00p0007d. JSTOR 2537759.

- Rubin, Barry (January 1998). "Israel, the Palestinian Authority, and the Arab States". Mideast Security and Policy Studies. 36. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- Sayigh, Yezid (1 September 2007). "Inducing a Failed State in Palestine". Survival. Routledge. 49 (3): 7–39. doi:10.1080/00396330701564786. Retrieved 2008-04-12.

- "Statement by Rodrigo de Rato Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund at the London Meeting on Supporting the Palestinian National Authority". UNISPAL. March 1, 2005. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- "The Palestinian Economy and the Prospects for its Recovery" (PDF). World Bank. December 2005. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- "The Palestinian War-Torn Economy: Aid, Development and State Formation" (PDF). United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- Turner, Mandy (1 December 2006). "Building Democracy in Palestine: Liberal Peace Theory and the Election of Hamas". Democratization. 13 (5): 739–755. doi:10.1080/13510340601010628.

- "Twenty-Seven Months - Intifada, Closures and Palestinian Economic Crisis - An Assessment" (PDF). World Bank. May 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-13.

- "Two Years after London - Restarting Palestinian Economic Recovery" (PDF). World Bank. September 24, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- "US Blocks Palestinian Aid". Middle East. BBC News. May 5, 2006. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- "West Bank and Gaza: An Evaluation of Bank Assistance" (PDF). OECD. March 7, 2002. Retrieved 2008-04-12.