Fluorosurfactant

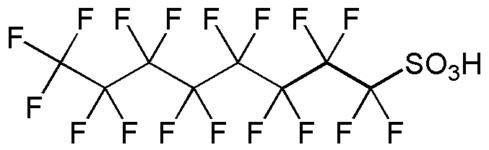

Fluorosurfactants (also fluorinated surfactants, perfluorinated alkylated substances or PFASs) are synthetic organofluorine chemical compounds that have multiple fluorine atoms. They can be polyfluorinated or fluorocarbon-based (perfluorinated).[1] As surfactants, they are more effective at lowering the surface tension of water than comparable hydrocarbon surfactants. They have a fluorinated "tail" and a hydrophilic "head." Some human-made fluorosurfactants, such as PFOS and PFOA, are persistent organic pollutants and are detected in humans and wildlife.[2]

Physical and chemical properties

Fluorosurfactants can lower the surface tension of water down to a value half of what is attainable by using hydrocarbon surfactants.[3] This ability is due to the lipophobic nature of fluorocarbons, as fluorosurfactants tend to concentrate at the liquid-air interface.[4] They are not as susceptible to the London dispersion force, a factor contributing to lipophilicity, because the electronegativity of fluorine reduces the polarizability of the surfactants' fluorinated molecular surface. Therefore, the attractive interactions resulting from the "fleeting dipoles" are reduced, in comparison to hydrocarbon surfactants. Fluorosurfactants are more stable and fit for harsh conditions than hydrocarbon surfactants because of the stability of the carbon–fluorine bond. Likewise, perfluorinated surfactants persist in the environment for that reason.[2]

Economic role

Fluorosurfactants play a key economic role for companies such as DuPont, 3M, and W. L. Gore & Associates because they are used in emulsion polymerization to produce fluoropolymers. Fluorosurfactants have two main markets: a $1 billion annual market for use in stain repellents, and a $100 million annual market for use in polishes, paints, and coatings.[5]

Health and environmental concerns

Fluorosurfactants such as perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA) have caught the attention of regulatory agencies because of their persistence, toxicity, and widespread occurrence in the blood of general populations[6][7] and wildlife. In 2009 PFASs were listed as persistent organic pollutants under the Stockholm Convention, due to their ubiquitous, persistent, bioaccumulative, and toxic nature.[8][9] Their production has been regulated or phased out by manufacturers, such as 3M, DuPont, Daikin, and Miteni in the USA, Japan, and Europe.

Some manufacturers have now replaced PTFOS and PFOA with short-chain PFASs, such as perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), perfluorobutanesulfonic acid[5] and perfluorobutane sulfonate (PFBS). Shorter fluorosurfactants may be less prone to accumulating in mammals;[5] there is still concern that they may be harmful to both humans,[10][11][12] and the environment at large.[13]

In 2017, the ABC's current affairs programme Four Corners reported that the storage and use of firefighting foams containing perfluorinated surfactants at Australian Defence Force facilities around Australia had contaminated nearby water resources.[14]

Class action lawsuit

In October 2018, a class action suit was filed by an Ohio firefighter against several producers of fluorosurfactants, including 3M and DuPont, on behalf of all US residents who may have adverse health effects from exposure to PFAS chemicals.[15]

Examples

- Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA)

- Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS)

- Perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS)

- Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA)

- Perfluorodecanoic acid (PFDA)

References

- ↑ Lehmler, HJ (2005). "Synthesis of environmentally relevant fluorinated surfactants—a review". Chemosphere. 58 (11): 1471–96. Bibcode:2005Chmsp..58.1471L. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.11.078. PMID 15694468.

- 1 2 Houde M, Martin JW, Letcher RJ, Solomon KR, Muir DC (June 2006). "Biological monitoring of polyfluoroalkyl substances: A review". Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 (11): 3463–73. Bibcode:2006EnST...40.3463H. doi:10.1021/es052580b. PMID 16786681. Supporting Information (PDF).

- ↑ Salager, Jean-Louis (2002). "Surfactants-Types and Uses" (PDF). FIRP Booklet # 300-A. Universidad de los Andes Laboratory of Formulation, Interfaces Rheology, and Processes: 45. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ "Fluorosurfactant — Structure / Function". Mason Chemical Company. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- 1 2 3 Renner R (2006). "The long and the short of perfluorinated replacements". Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 (1): 12–3. Bibcode:2006EnST...40...12R. doi:10.1021/es062612a. PMID 16433328.

- ↑ Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL (2007). "Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003-2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999-2000". Environ. Health Perspect. 115 (11): 1596–602. doi:10.1289/ehp.10598. PMC 2072821. PMID 18007991.

- ↑ Wang, Zhanyun; Cousins, Ian T.; Berger, Urs; Hungerbühler, Konrad; Scheringer, Martin (2016). "Comparative assessment of the environmental hazards of and exposure to perfluoroalkyl phosphonic and phosphinic acids (PFPAs and PFPiAs): Current knowledge, gaps, challenges and research needs". Environment International. 89–90: 235–247. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2016.01.023. ISSN 0160-4120.

- ↑ Blum, Arlene; Balan, Simona A.; Scheringer, Martin; Trier, Xenia; Goldenman, Gretta; Cousins, Ian T.; Diamond, Miriam; Fletcher, Tony; Higgins, Christopher; Lindeman, Avery E.; Peaslee, Graham; de Voogt, Pim; Wang, Zhanyun; Weber, Roland (2015). "The Madrid Statement on Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs)". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (5): A107–A111. doi:10.1289/ehp.1509934. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 4421777. PMID 25932614.

- ↑ "Stockholm Convention Clearing". chm.pops.int. Secretariat of the Stockholm Convention. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ↑ Wang, Zhanyun; Cousins, Ian T.; Scheringer, Martin; Hungerbuehler, Konrad (2015). "Hazard assessment of fluorinated alternatives to long-chain perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) and their precursors: Status quo, ongoing challenges and possible solutions". Environment International. 75: 172–179. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.013. ISSN 0160-4120.

- ↑ Birnbaum, Linda S.; Grandjean, Philippe (2015). "Alternatives to PFASs: Perspectives on the Science". Environmental Health Perspectives. 123 (5): A104–A105. doi:10.1289/ehp.1509944. ISSN 0091-6765. PMC 4421778. PMID 25932670.

- ↑ Perry, Melissa J.; Nguyen, GiaLinh N.; Porter, Nicholas D. (2016). "The Current Epidemiologic Evidence on Exposures to Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) and Male Reproductive Health". Current Epidemiology Reports. 3 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1007/s40471-016-0071-y. ISSN 2196-2995.

- ↑ Scheringer M, Trier X, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, Fletcher T, Wang Z, Webster TF (2014). "Helsingør Statement on poly- and perfluorinated alkyl substances (PFASs)". Chemosphere. 114: 337–339. Bibcode:2014Chmsp.114..337S. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.05.044.

- ↑ "'Shocked and disgusted' Katherine residents demand action on PFAS contamination". ABC News. 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ↑ Sharon Lerner (October 6, 2018). "Nationwide class action lawsuit targets Dupont, Chemours, 3M, and other makers of PFAS chemicals". The Intercept. Retrieved October 8, 2018.

Further reading

- Andrew B. Lindstrom; Mark J. Strynar; E. Laurence Libelo (2011). "Polyfluorinated Compounds: Past, Present, and Future". Environmental Science & Technology. 45 (19): 7954–7961. Bibcode:2011EnST...45.7954L. doi:10.1021/es2011622.

- Stephen K. Ritter (2015). "The Shrinking Case For Fluorochemicals". Chemical & Engineering News. 93 (28): 27. doi:10.1021/cen-09328-scitech1.