Flavian Palace

Coordinates: 41°53′19″N 12°29′12″E / 41.88861°N 12.48667°E

| Domus Flavia | |

|---|---|

Domus Flavia on the Palatine | |

| Location | Palatine Hill |

| Built in | 92 AD |

| Built by/for | Domitian |

| Type of structure | Domus |

| Related |

List of ancient monuments in Rome |

Domus Flavia | |

The Flavian Palace, normally known as the Domus Flavia, is part of the vast residential complex of the Palace of Domitian on the Palatine Hill in Rome. It was completed in 92 AD by Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus,[1] and attributed to his master architect, Rabirius.[2]

The term Domus Flavia is a modern designation used to describe the northwestern section of the Palace where the bulk of the large public rooms for entertaining and ceremony are concentrated.[3] It is interconnected with the domestic wing to the southeast, the Domus Augustana, which descends from the summit of the Palatine down to wings specially constructed within the hill to the south and southwest.

The imposing ruins which flank the southeastern side of the Palace above the Circus Maximus are a later addition built by Septimius Severus; they are the supporting piers for a large extension which completely covered the eastern slope.

Layout

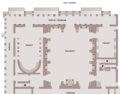

The Domus Flavia contains several exceptionally large rooms; the main public reception rooms are the Basilica, the Aula Regia, the Lararium, and the Triclinium.

The Basilica is the first part visible from the Clivus Palatinus, the road that connects the Roman Forum to the Palatine Hill. A long portico (Po) runs alongside the domus on the west and north sides at the end of which is the main entrance (E) which seems to serve both the public and the private part of the palace. Once inside the visitor enters the Lararium (L) housing a detachment of the Praetorian guard. It is the smallest and most poorly preserved room in the palace. Behind it was once a staircase providing access to the Domus Augustana. Below this room parts of the earlier House of the Griffins have been excavated and from which exquisite decorations have been removed to the Antiquarium.

The next room is the Aula Regia used for the daily "salutatio" to the Emperor and to host important receptions and embassies. In the time of Domitian, the walls had a marble veneer, and there were Phrygian marble columns and an elaborately carved frieze. The wall at the back is occupied by an apse flanked by two doors. On the wall in front opens a wide single door which leads to the peristyle. The coffered ceiling is more than 30 m above the ground.

The Basilica is a long room with a central nave where the Emperor presided over legal cases and performed his judicial functions, and assembled his advisers to take political and administrative decisions concerning the Empire. Beneath the Basilica the Aula Isiaca[4] has been excavated, a room with frescoes of about 30BC and probably once part of the Domus Augusti.[5] This was in turn built over by Nero's Domus Transitoria.

In the centre was a huge peristyle garden filled almost completely with a pool surrounding an octagonal island with a labyrinthine pattern complete with fountains and water features. Suites of rooms lay to the north and south.

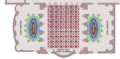

Along the southwest side of the peristyle, is the 2nd largest room in the Palace, the cenatio (or Triclinium) or Banqueting Room. Like the Aula Regia, it was extravagantly decorated, with several tiers of columns in exotic marbles and a frieze.[6] It opened onto two courtyards with oval fountains to the north and south visible from the windows of the dining room. The centre of the southern wall of the hall has an apse surrounded by two passages which allow access to the library of the temple of Apollo. The floor of the hall is covered with marble concealing a hypocaust whose bricks date from the reign of Maxentius. This heating system suggests that this hall served as a banqueting hall in the winter and has been identified with the Cenatio Iovis mentioned in ancient literary sources.[7]

Beneath the floor of the cenatio have been found traces of two earlier versions both built by Nero.[8]

_(14598004200).jpg)

.png) Map of Aula Regia

Map of Aula Regia Northern part of Domus Flavia (Aula Regia, basilica and lararium)

Northern part of Domus Flavia (Aula Regia, basilica and lararium) Center part (peristilium)

Center part (peristilium) Southern part (Cenatio Iovis)

Southern part (Cenatio Iovis)

The Flavian Palace in contemporary times

The poet Statius, a contemporary of Domitian, described the splendor of the Flavian Palace in Silvae, IV, 2:

Awesome and vast is the edifice, distinguished not by a hundred columns but by as many as could shoulder the gods and the sky if Atlas were let off. The Thunderer’s palace next door gapes at it and the gods rejoice that you are lodged in a like abode […]: so great extends the structure and the sweep of the far-flung hall, more expansive than that of an open plain, embracing much enclosed sky and lesser only than its master.[9]

Scholars usually identify this room as the Triclinium, but it could possibly be the Aula Regia, which was distinguished by its number of columns.[2]

The Flavian Palace was one of Domitian’s many architectural projects, which also included the Domus Augustana, a contribution to the Circus Maximus, a contribution to the Pantheon, and three temples deifying his family members: the temple of Vespasian and Titus, the Porticus Diuorum, and the Temple of the gens Flavia.[2]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Domus Flavia. |

References

- ↑ The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. XI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- 1 2 3 Darwall-Smith, Robin Haydon. Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome. Brussels: Latomus Revue D'Etudes Latines, 1996.

- ↑ Robathan, Dorothy M. "Domitian's 'Midas-Touch'". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association 73 (1942): 130-144.

- ↑ http://www.archeoroma.com/Palatino/aula_isiaca.htm

- ↑ Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide, A. Claridge, 1998 ISBN 0-19-288003-9, p. 148

- ↑ Darwall-Smith, Robin Haydon. Emperors and Architecture: A Study of Flavian Rome. Brussels: Latomus Revue D'Etudes Latines, 1996

- ↑ Statius, Silvae 4.2 18-31 (AD 93-4)

- ↑ Rome, An Oxford Archaeological Guide, A. Claridge, 1998 ISBN 0-19-288003-9, p. 136

- ↑ Statius. Silvae IV. Trans. K.M. Coleman. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.