First Robot Olympics

The First Robot Olympics.[1] took place in Glasgow,[2] Scotland on 27–28 September 1990.[3]

The event was run by The Turing Institute at the Sports Centre at the University of Strathclyde. It featured 68 robots from 12 different countries and involved over 2,500 visitors over the two-day period.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

Background

During the 1980s the Turing Institute had been involved in a wide range of robotics activities and had developed links with many leading robotics laboratories as a result of both student exchange and a series of collaborative research projects.[12]

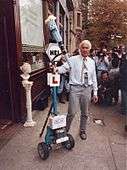

The event was conceived and directed by Dr Peter Mowforth, Director of the Turing Institute, as an events-based meetup for robot enthusiasts and builders.[13][14] Although there had been single event competitions and national events for competing robots, this was the first time that such a large, varied and international Robot Competition had taken place.[15]

Many of the robots that came to the event reflected key research themes that were present at the time. For example, the two-wheeled balancing 'torch carrying' (pre-Segway) robot[16] that opened the event was associated with the Institute's work on using machine learning applied to the inverted pendulum[17]

Strathclyde University was an academic associate of and adjacent to the Turing Institute.[18] The University made their sports hall complex available for the two day event.

Events and results

| EVENT | Gold | Silver | Bronze |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obstacle Avoidance | ASTERIX. University of Toronto, Canada. Anthony Green & Pavel Rozalski | OSCAR. AI Dept. Edinburgh University. Scotland | YAMABICO. Tsukuba University, Japan. Shoji Suzuki |

| Pole Balancing | PENDULUM. Salford University, England. F Nagy & G A Medrano-Derda | LANKY. Lancaster University, England | MENACE, Turing Institute, Scotland. Bing Zhang |

| Phototrophic | ALPHA PHOTON. Kent University, England. David Bisset | ICARUS. The Shadow Group, England. David Buckley. | |

| Manipulators | BELGRADE/USC HAND. University of Belgrade, Yugoslavia | BCI. St Patricks High School, Coatbridge, Scotland. | |

| Biped Race | CARDIFF BIPED.[19] Uni. Wales, Cardiff, Wales. Paul Channon, Simon Hopkins & Prof Pham | ROBBIE. Paisley College of Technology, Scotland. Ken MacFarlane, Gordon Allan | |

| Javelin | YORK ARCHER. Museum of Automata, York, England | WILBERFORCE. East London Polytechnic, England. Martin Smith | ELEPHANTS TRUNK. Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland. J B C Davies, J Morrison |

| Multi-Legged Race | PENELOPE. Edinburgh University, Scotland. D J Todd | GENGHIS. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, AI Lab, US. Olaf Beck, Prof. Rodney Brookes & Colin Angle | |

| Wall Following | YAMABICO. Tsukuba University, Japan. Shoji Suzuki | SAM. Kent University, England. David Bisset, Jason Garforth, Jeremy Laycock | |

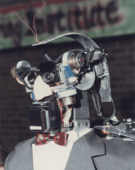

| Talking | RICHARD 1ST. Turing Institute, Scotland. Ketil Undbekken, Peter Mowforth | SHADOW WALKER. The Shadow Group, London, England. David Buckley | |

| Wall Climbing | ZIG ZAG. Portsmouth Polytechnic, England. A A Collie,[20] J Billingsley, R P Smith | RVP II. Soviet Academy of Sciences, Moscow, USSR. Professor Chernousko, Professor Gradetsky | RVP I. Soviet Academy of Sciences, Moscow, USSR. Professor Chernousko, Professor Gradetsky[21] |

| Behaviour | GENGHIS. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, AI Lab, USA. Olaf Beck, Prof. Rodney Brookes & Colin Angle | SHEEP & SHEEP DOG. Computer Science, Strathclyde Uni. Scotland | SIAS. City Montessori School, Lucknow, India. Mr Ashish Panwar |

National medals table

| Country | Gold (3 points) | Silver (2 points) | Bronze (1 Point) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | 4 | 5 | 0 | 22 |

| Scotland | 2 | 4 | 2 | 16 |

| USA | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Japan | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| USSR | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Yugoslavia | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Wales | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| India | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Mexico | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disqualifications

Four judges supervised the events to ensure 'fair play'. They were:

- • Professor Frank Nage, University of Salford

- • Professor Ruzena Bajcsy, University of Pennsylvania

- • Eddie Grant (IEEE Representative, University of Strathclyde)[22]

- • Professor Hans P. Moravec, Carnegie Mellon University[23]

| Robot | Event | Reason for disqualification |

|---|---|---|

| YAMABICO, Japan | Talking | Could not speak English |

| SIAS, India | Talking | Completely incomprehensible |

| ROBUG II, England | Wall Climbing | Veering out of lane and demonstrating inappropriate behaviour in front of children. |

| MEXBOT, Mexico | Multi-Legged Race | Damaged during transportation. Dropped when offloaded from ship in UK. |

Special awards

Several organisions provided special awards for different categories of competition.

IEEE Robotics & Automation Society Young Roboticist Award Brian Carr (School pupil), St Patricks High School, Coatbridge, Scotland. Awarded £25 book token.

NatWest Bank Prize for Technology Transfer Olaf Beck, Prof. Rodney Brookes & Colin Angle, Massachusetts Institute of Technology MIT, AI Lab, USA Awarded with a Caithness Crystal bowl and £200 from NatWest Bank.

'Turing Institute Best School Prize' XYBOT Inverkeithing School, Class 7S, Scotland. Awarded with a cup and a cheque for £100.

'Olympic Champion' YAMABICO from Tsukuba University, Japan. Prize given to Shoji Suzuki. Awarded with a Caithness Glass Trophy.

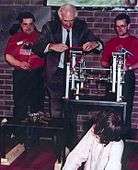

Photographs

Sponsorship

As well as being organised by The Turing Institute and hosted by the University of Strathclyde, the event had seven main sponsors:

- NatWest Bank (London)[24]

- IEEE (Robotics & Automation Society)

- Scottish Development Agency

- Stakis Hotels (Glasgow)

- Caithness Glass

- Holiday Inn (Glasgow)

- British Gas (Olympic Torch and Olympic flame)

References

- ↑ "Guinness World Records: First Robot Olympics". guinnessworldrecords.com/. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "Glasgow's Guinness World Records". Glasgow Living. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Children's Britannica : yearbook 1991. London: Encyclopædia Britannica. 1991. p. 90. ISBN 0-85229-228-7.

- ↑ Tim Willard. "No Relay Race on This Olympic Field". Los Angeles Times. World Future Society. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Gavaghan, Helen (1990). "Mechanical athletes totter towards Olympic glory". New Scientist (1737).

- ↑ "L' OLIMPIADE DEI ROBOT". La Repubblica. 1990. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Grabowski, Rainer (1991). "immer an der Wand lang : die erste Roboter Olympiade". CHIP (1/91): 314–318. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ "Machines strut their wizardry; Japanese entry wins gold medal in 1st Robot Olympics" (29 September). Chicago Tribune. 1990. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ "Robot Olympics". Agenda (Italy). Agenda Magazine. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Ken, MacFarlane (1991). "Sporting (and unsporting) Robots". Electronics World & Wireless World. January: 54. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ "The chips are down" (1 June). Sunday Herald. Herald. 1990. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- ↑ Lamb, John (1985-08-22). "Making Friends with Intelligence". New Scientist: 30–32. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "Pete Mowforth With Lorraine Kelly". WN. World News Network. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ LEWIS, Alun (1990). "SCience Now" (19901002). BBC. Radio 4. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Buckley, David. "1st Robot Olympics". DavidBuckley. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "Trolleyman Lighting Olympic Flame". Science Photos. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ McGee, Grimble and Mowforth. Knowledge-based Systems for Industrial Control. P. Peregrinus Limited. ISBN 978-0863412219.

- ↑ "Turing Institute". University of Strathclyde Archives. Strathclyde University. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "UWCC biped robot in action at Robot Olympics". GalloImages. The Science Photo Library. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Collie, Arthur. "Professor Arthur Collie". Scotsman. The Scotsman. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ↑ Felix L. Chernousko, Nikolai N. Bolotnik and Valery G. Gradetsky. Manipulation Robots. CRC Press. p. 245.

- ↑ Grant, Edie. "Biography". NCSU. NC State University. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ Moravec, Hans. "Biography". Carnegie Mellon University. CMU. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ↑ "NatWest bank's advertising robot". Science Photo. Science Photo Library. Retrieved 8 November 2015.